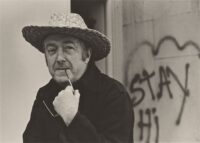

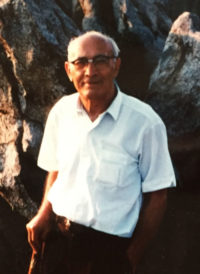

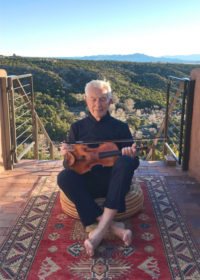

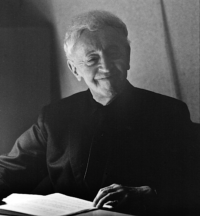

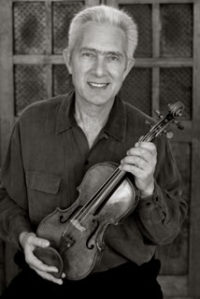

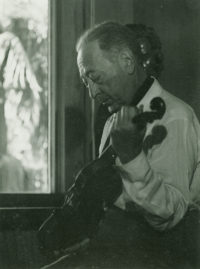

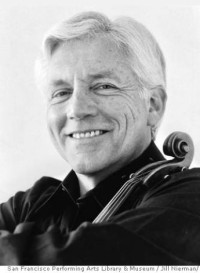

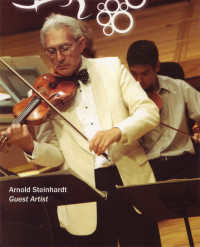

Tom

August 1, 2013

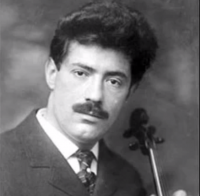

I met Tom Heimberg during junior high school recess when we were both twelve years old. The popular sport during recess was something we unofficially called Chinese handball—a game played with a rubber ball against an upright surface. Tom and I became quite professional at discussing topspin, slices, drop shots, and fake outs, but as the summer of 1949 approached, I could not have imagined that our friendship would last a lifetime. What twelve-year-old thinks in those terms?

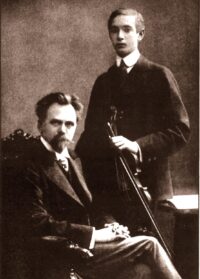

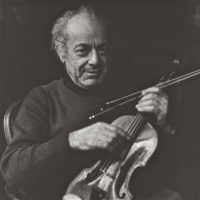

Tom and I shared another skill I soon discovered when I joined the school orchestra. We both played the violin. As one of the less advanced violinists in the orchestra, Tom sat at the very back of the violin section. I, on the other hand, was already quite good for my age and immediately placed by Mr. Ives, the school music teacher and orchestra conductor, next to Clementina, the orchestra concertmaster.

Mr. Ives instituted something called orchestra challenges, which took place every month or so. During challenges, if you were sitting, say, 5th chair cello and you considered yourself better than, say, 2nd chair, you were free to announce a challenge. First the challenger and then the challenged played. Then the whole orchestra delivered their preference by a show of hands.

Challenges were fun. Clementina and I challenged each other at every opportunity for the concertmaster chair. Sometimes she won, sometimes I did. At no time during the semester’s many school challenges, did Tom even seem interested in a better seat in the violin section.

Over the summer, I dutifully practiced many hours daily, with unexpected benefits. When school orchestra recommenced in September, I was voted concertmaster by a significant number. The accomplishment must have gone to my head, however, for I soon learned that fellow orchestra members were annoyed with my behavior. Apparently, I had begun to consider myself God’s gift to the violin.

At the next orchestra challenge, Tom unexpectedly stood up and announced with imperious formality that he, Tom Heimberg, last chair violin, would like to challenge the concertmaster, Arnie Steinhardt, for his chair. There were a few stifled laughs and an astonished half smirk from me, but Tom, undaunted, launched into Brahms’ Hungarian Dance #5. To be honest, his playing was less than wonderful, but rather than responding graciously with a modest solo, I decided to show off my abilities as God’s gift to the violin with Monte’s Czardas, a showpiece in the gypsy style. Afterwards, I smugly sat down with the confidence that I had retained my seat—a confidence that proved unfounded: the orchestra, deciding to have a little fun at my expense, voted overwhelmingly for Tom. Tom swaggered up to the concertmaster chair like a Roman emperor and I was demoted to his place in the back. At rehearsal’s end, however, Mr. Ives said the joke had gone far enough and returned us to our former positions.

For reasons I cannot quite explain, this event sealed Tom’s and my friendship.

Some time ago I came across this graduation inscription in my 1951 junior high school yearbook:

Roses are red,

Violins are blue?

Here’s wishing

luck to you.

— Tom Heimberg

Parodies of the Roses are Red, Violets are Blue poem were often yearbook items, but Tom’s attested to the fact that we already shared some violin history. By then, we had played together in the school orchestra’s violin section for at least a couple of years.

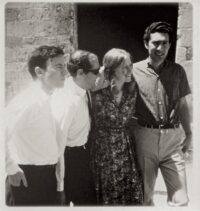

We stayed friends in high school. Common interests undoubtedly held us together—music, of course, but also books and chess (Tom was very good, I mediocre). When we graduated, I went east to the Curtis Institute of Music and Tom rented my room from my parents while he attended college in Los Angeles.

Dad had a philosophy of professional achievement that he repeated endlessly when he heard me practicing: “There is only room at the top,” he would intone solemnly. The message was crystal clear: either I became the next Albert Einstein, Jonas Salk, or in my case, Jascha Heifetz, or I would risk thrashing about in a cruel and unpredictable world. When Tom moved into my room, he took my place in the living room as the resident practicing violinist. He was clearly a gifted musician, but he was still grappling with the instrument’s many difficult hurdles, and when he told my parents he hoped to become a professional musician, they could only sadly shake their heads. A brilliant Phi Beta Kappa student, with a degree in English, Tom clearly had many career possibilities open to him. Yet what hope did he have as a musician in comparison to Mom and Dad’s heroes—Heifetz, Mischa Elman, and Nathan Milstein—the reigning violin stars whose records they listened to worshipfully.

At music school, I soon encountered students already endowed not only with solid musical ability but also with breathtaking virtuosity. They were the musicians who might some day occupy that very small room at the top Dad so often spoke of. But were there no other rooms in the entire profession for someone like Tom? He certainly had the discipline needed for a career in music. His practice habits were faultless. Even his playful orchestra challenge those many years earlier was a clue to his strength of character. But the engine that seemed to drive him ever forward was his passionate and unwavering love of music and the violin (and viola, which he would soon take up). Tom was cut out of a template that I would admire more and more as time went on.

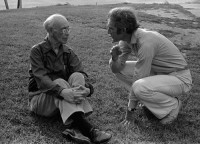

One evening, when I was just back from music school, Tom and I sat on our living room sofa and chatted. Unexpectedly, the sound of a songbird coming from an open window began to intrude on our conversation. Finally we stopped talking altogether and listened in rapt silence to a performance of intoxicating beauty and never-ending variety. We listened for the better part of an hour. Without saying it, we must have sensed that there were untold miracles in this world waiting to be discovered and shared as we ventured out into adult life.

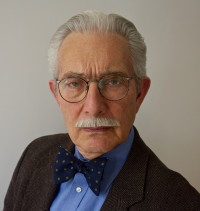

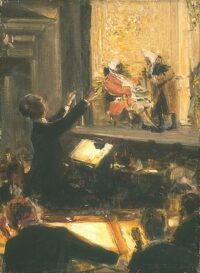

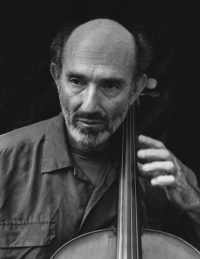

You might call the songbird’s concert a small event, but such things were treasures to Tom. As he made his way slowly but surely up the professional ladder—first as a violist in the Oakland Symphony, then the San Francisco Symphony, and finally the San Francisco Opera Orchestra, as well as orchestra manager, teacher, and author—I would hear some of his small stories when I came to visit. I would hear about a gorgeous clarinet solo, about a funny remark from his stand partner, or the latest carpool stories. These vignettes were told with the relish and detail of someone who never lost his wide-eyed love of music, of musicians, of life itself.

Tom Heimberg passed away on November 14, 2006. Since there was no room at the top, Tom created a special space for himself and his viola elsewhere.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

Just quickly, I remember Tom during many encounters at your parents parties for the mishpocha. He was a creative witty warm person with chutzpah to spare. Until now, I didn’t realize that he had a professional musical career. He was taken too soon.

Gene

Thank you for this very moving and thoughtful post. Tom’s achievements were perhaps all the more admirable, given that he was not at the top tier in natural gifts. But this also leaves me wondering what happened to Clementina.

Dear Arnold:

I read your wonderful story of Tom. My wife Carole Bailis and I are fans of your blog.

On a lesser note( a pun), I remember the chinese hand ball. It was called something else.

A pejorative name “Chink”. We are also the host family of Nigel Armstrong and sat behind you at his graduation recital at Curtis.

We’re in Aspen and hope to meet up wth Nigel next week.

Best regards………AB & CB

Arnold, this is a beautiful tribute to Tom. I didn’t know he had died.

Paula

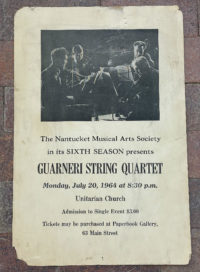

Thank you, thank you, thank you, for this wonderful story! Tom was my mentor as an Orchestra Contractor here in the San Francisco area. He taught me so much about hiring an orchestra, and life in general. I admired loved him very much! He died the same week that my mother did, and it was a dark few months following that. I still miss him very much. As for you, Mr. Steinhardt, I heard you with the Guarneri Quartet in the late ’60s in St. Louis, when I was a student at Washington University. Your playing astonished me. I’m a huge fan!

My memories of Tom are regrettably only from my adolescent years. I admired his brilliance, his humor, his passion for music, his extraordinary physical flexibility, his remarkable youthful wisdom and his personal warmth. Thank you for this wonderful tribute to his memory!

An absolutely beautifully written piece. So moving I am compelled to comment. Thank you.

Arnold, I was just thinking about our friendship between Paolo, you, Dodo and I, and sharing with my grand-daughter Fernanda (eleven years old), how important is to take care of her friends and try to last them for an entire life!

Your story touch my heart! Love, Maru

Dear Arnold Tonight I was feeling a little blue and could not sleep soooooo I played on my computer. I came upon your beautiful memorial to Tom. How fortunate we were to have shared his beautiful spirituality and gentle humor. He was a lovely man and I will always remember him as a person that enriched the lives of all that had the good fortune to know him. I am crying but tears of gratitude for the lovely memorey you have brought me,

Love Arianne

Arnold, what a gift for you and Tom to have shared this wonderful, enduring friendship. I am sure that he is smiling down on you right now. I was very touched by your tribute to Tom–thank you!

I’m sure you do not remember this, but when I was a young buck you passed my name to Tom so that he might hire me now and then to play with the SF Opera. As it turned out, I spent many an evening sitting on a stand with Tom, playing everything from Rossini to Wagner. I am lucky to have learned from both you and Tom, and to this day make a living playing both opera and chamber music.

I didn’t know Tom, but I wish I did, and well now I do. Thanks Arnold. I love the way you bring alive wonders of this life we all share with your words, and your violin.

A chance encounter with the book Making a Musical Life put Tom Heimberg on my radar. The wisdom expressed in his writings and the good qualities all who knew him extol place him at the top in every way that matters.

Leave a Comment

*/