The Homecoming

May 4, 2016

Kirk Browning, an American television director and producer with hundreds of productions to his credit had decided to move into smaller quarters. Our mutual friend, Virginia, was there to assist as Kirk regretfully disposed of many of the awards, trophies, and memorabilia that he had amassed over a lifetime of professional work.

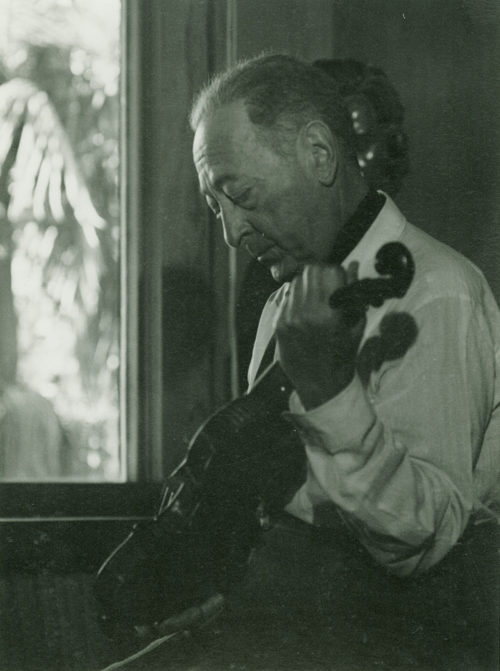

At one point, Virginia noticed that Kirk was about to drop two publicity photos of a musician holding his violin into the trash bin. Even from afar, one of the photos caught her eye. The violinist, dressed informally but elegantly, seemed engaged in deep thought as he gazed down at his instrument. The photograph was compelling enough for Virginia to ask Kirk about it. The musician in question was Jascha Heifetz, one of the greatest violinists of all time. Kirk told Virginia that he had met and worked with Heifetz as the director of the 1970 French television production, Heifetz in Performance. Somewhere along the way, Kirk had acquired these two Heifetz photos. One of them never made it into the trash bin. Knowing that I was a violinist, Virginia presented it to me the next time we met.

Photo: Glenn Embree

There are great violinists. And then there is Heifetz. Listening to him, my heart always beat faster and my palms began to sweat. How was it humanly possible to play the violin not only with that kind of mind-bending accuracy, but also with such daring, such mesmerizing changes of color and such seeming effortlessness? Heifetz played as if he were a hummingbird, able to impulsively dart forward, then miraculously stop on a dime, and just as suddenly change speed and soar into the stratosphere for sheer pleasure.

The photo Virginia so thoughtfully gave me captured a meditative and intimate moment quite unlike most glittering Heifetz publicity shots I had seen over the years. One of those photos, with Heifetz’s violin held theatrically high and his left hand fingers extended on the upper reaches of the fingerboard as if Mount Everest-bound, found a spot in my violin case. I had placed the photo there to honor the violinist I had worshipped from childhood on, but also to inspire me now. Heifetz, supremely endowed as a violinist and artist, could have coasted to a successful career on those attributes alone, but he felt compelled to practice many hours a day throughout his life. If even Heifetz had that obsessive work ethic, so, perhaps, should I.

I heard Jascha Heifetz live several times when I was young. No violinist looked cooler on stage than Heifetz, yet with a minimum of facial gestures or body movement he managed to perform with a feverish intensity that made me feel his violin would burst into flames at any moment. But as Heifetz grew more renowned over time, so did his reputation as a difficult man. For whatever reason–perhaps his great fame, the adoring, even fawning fans that came with it, or the constant pressure to be the Heifetz everyone expected of him–the great violinist often became willful, suspicious of people’s motives, and withdrawn from even his oldest friends.

People gleefully tossed around stories of Heifetz’s bad behavior. Jack Pfeiffer, who was the artist and repertoire man at RCA records for both our Guarneri String Quartet and Jascha Heifetz, told us that one day Heifetz called him to discuss a recording project they had just finished. When the conversation ended, Jack said, “Thanks for the information, Mr. Heifetz. By the way, how are you?” Heifetz’s response was immediate. “I called you. If you want to know how I am, you call me.”

Yes, the story was amusing, but it was also heartbreaking. The dazzling high-wire act Heifetz successfully performed for decades had turned him, with few exceptions, into a fiercely burning flame encased in ice. For this reason, the Heifetz photo I now held in my hands was especially meaningful. Gone was the icy exterior. What remained was the image of a deeply sensitive man lost in contemplation–a man who could at one moment leave me breathless with his violin, and at another just as easily bring tears to my eyes.

I hung the Heifetz photo in a place of honor in our house where it remained for many years.

In 1938, shortly after moving to Southern California, Heifetz asked his friend Lloyd Wright, architect son of Frank Lloyd Wright, to design and build a studio behind his house overlooking Beverly Hills. The Heifetz studio was conceived as a cluster of hexagonal spaces and linked to the main house by a breezeway. After Heifetz died in 1987 at age 86, the new owner, actor James Wood, planned to tear the studio down. Fortunately, Richard D. Colburn, founder and benefactor of the Colburn School in downtown Los Angeles, and Toby E. Mayman, its executive director, came to the rescue by raising enough money to have the studio dismantled piece by piece and then reconstructed in 1999 inside the Colburn School.

The Heifetz studio

Some ten years later, as a new member of the Colburn School faculty, I found myself surreally standing in the reconstructed Heifetz studio. The school’s distinguished violin teacher Robert Lipsett, who teaches in the studio, had invited me in. Every effort had been made to exactly restore both the studio and its contents. Across from a handsome brick and stone fireplace was the black leather desk chair Heifetz had sat in; nearby a Rachmaninoff poster and a bust of Beethoven, as well as smaller items such as a cartoon Heifetz had pasted to the side of a cabinet in which an unhappy customer is complaining to the owner of a car repair shop about a bill: “$120.34 for a tune-up? Who tuned it? Jascha Heifetz?”

But if I were to ascribe significance to any object in the room, it would be to the inauspicious music stand on which Heifetz had placed his music. Day after day, year after year in front of that stand, he had obsessively practiced in order to perform the miracle we would later hear on stage. Heifetz himself was once quoted as saying: “Practice as if the world depends on it. Perform as if you don’t give a damn.” For almost a half a century, practice in this studio had been the genesis of literally thousands of electrifying Heifetz performances.

When I returned home after having been in the Heifetz studio, the photo of him that hung in my house had somehow changed. Beforehand, I would occasionally stop to gaze at it, always relishing the very personal and intimate mood that the photographer had managed to capture of Heifetz himself. Now, with the studio fresh in my mind, I began to look past Heifetz. Could that be a bust of Beethoven behind Heifetz’s head? And what about the semitropical-looking vegetation growing outside the window? The thought suddenly occurred to me that the photo might possibly have been taken in Heifetz’s very own studio.

I brought the photograph to my old friend Marianne Wurlitzer, a music antiquarian who deals in a unique music gallery that includes everything from a Beethoven first edition to a French hurdy-gurdy. In taking the photo out of its frame, Marianne discovered the name of the photographer, Glenn Embree, clearly stamped on the back. Embree was a highly respected commercial photographer known for his work with both cars (antique and otherwise) and stars (Hollywood rather than celestial). Then Marianne scanned and sent the photo image to John Maltese who together with his father has been in the process of writing a book about Heifetz. John, immersed in everything and anything concerning the violinist, informed us that the photograph had indeed been taken in Heifetz’s studio.

With that in mind, I gave the photograph to the Colburn School so that it might reside where its life had begun so many years ago. On my next visit there, Bob Lipsett ushered me into the studio and showed me where the photograph now hung. According to Bob, it occupied exactly the same place where Heifetz had posed for his portrait.

Robert Lipsett in the Heifetz studio. Heifetz photo to the left.

Bob and I stood in silence for a moment, looking reverently at the photograph that offered a glimpse into the soul of a very private man and a very great artist, and I thought to myself: Welcome home, Mr. Heifetz.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

Another of your heartwarming stories. Thank you!!!

I have heard many stories about Mr. Heifetz and his rather difficult personality, but in this story you managed to capture both his amazing talent, and his personal challenges, though a very humane and compassionate lens. Your humanity combined with your great talent is an inspiration for us all. Thank you.

Arnold,

Very beautiful article about Heifetz.

Paula

Arnold, your stories are heartrending and so beautifully written. I look forward to them always.

Anne Tatnall from long ago

Dear Arnold,

Here I sit in Venice Beach, Calirornia, and a delighted to be reading your so interesting story about this photograph. Being a photographer myself, the journey of the photo holds special interest. Thx for sharing it!

X.

The stories from In the Key of Strawberry seem to get better and better….just HOW does this fellow, Steinhardt, do it?? Since I, too, am infected with the Heifetz virus, I truly was glued to the words of this latest installment of the Strawberry Chronicles. One of my favorite authors is John Steinbeck….and Arnold’s intimate style of writing is just what this reader appreciates and loves.

Charles Avsharian

My mother was 18 and Principal Oboe of Houston Symphony in 1945 when Heifetz performed the Brahms Concerto with them. She has a copy of the program with his autograph and he wrote “All Good Wishes, with my Compliments” and signature. Nothing nasty about that!

Marvelous history of this violinistic giant for all of us to share, Arnold. Thanks.

But tell me. please; when I enlarged the photo methinks I spied a shoulder rest on the bottom of the violin. Could that have indeed been a shoulder rest, which I thought he abhorred, or rather a part of a music stand next to the lower part of the violin?

Inquiring minds want to know.

Bernie Zaslav

Fantastic!!! Picture are more than pictures!!! Amazing,

Lovely story. Thank you for sharing it.

Leave a Comment

*/