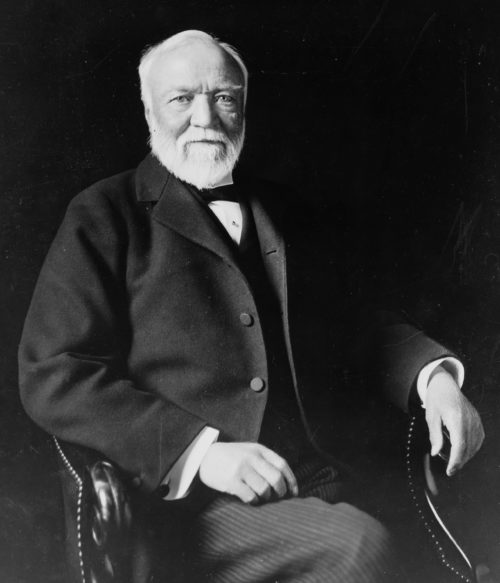

Andrew Carnegie

October 4, 2017

How do you get to Carnegie Hall?

I know. I know. Practice.

Or take the subway.

Or hail a cab.

Or if the year is 1891, take the trolley from 14th Street, the center of town, to the end of the line and walk two blocks north to 57th Street and 7th Avenue. You’ll find Andrew Carnegie’s new Music Hall there in the middle of the boondocks.

A couple of months ago, however, I found another and totally unexpected way to get to Carnegie Hall. My friend Gwen DeLuca won a raffle for a guided tour of Carnegie by its official archivist Gino Francesconi. Gwen invited me and several other friends to come along.

I didn’t even have to practice.

We met Francesconi, a warm and outgoing man in his middle years, in Carnegie Hall’s lobby. To my surprise, Francesconi told me that he had personally escorted me onto Carnegie’s stage several times when I had performed there. Francesconi’s unlikely career path began as a lowly Carnegie usher, then working backstage, moving on to become a conducting student under the guidance of conductor Carlo Maria Giulini, and finally assuming the distinguished role of Carnegie Hall’s archivist and director of its museum.

During the next two hours, Francesconi led us on a fascinating tour of Carnegie Hall, told of the many twists and turns in its vaunted history, and reveled in delightful and often highly personal stories about the artists who have graced its stage. Francesconi possessed more facts than you could count, but what made the tour memorable and irresistible was his boyish enthusiasm and his obvious love for everything concerned with Carnegie Hall.

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie, born in Scotland in a tiny, humble, grey stone cottage, rose to become one of the wealthiest and most powerful American business titans. Admirably, he spent the second half of his life giving away his money. Thrilled as he was to be a financial success, Carnegie aspired to be a man of letters. Throughout his life he read widely and cultivated friendships with some of the world’s most distinguished authors. Music apparently played a lesser role. Carnegie did not look upon what was eventually renamed Carnegie Hall as philanthropy and expected the hall would support itself financially. Who would have imagined that a building with this kind of challenging financial future, built in the wrong part of town, and whose architect had little experience, would become one of the greatest concert halls in the world?

Carnegie must have felt the need for a big name to inaugurate his new hall with a splash. He invited Peter Ilych Tchaikovsky, one of the most revered composers of his time, and offered Tchaikovsky the kind of money that the great Russian simply could not refuse.

Francesconi relished telling us about Tchaikovsky’s questions as he prepared for his trip to New York City: Is it safe to drink the water? What kind of hats do men wear? Where can I do my laundry? Then Francesconi went on to describe in detail the success of the opening concerts and how Tchaikovsky’s celebrity status sparked masses of

dinner invitations and autograph seekers.

From there, his talk left Tchaikovsky and proceeded through a parade of legendary artists who had appeared in Carnegie Hall over the years—everyone from Jascha Heifetz, to Benny Goodman, to Leonard Bernstein, to the Beatles. But then, more or less at the hall’s hundred-year mark, its future abruptly turned bleak. Due to shifting financial conditions, this icon of American music seemed headed for the wrecking ball.

Enter the distinguished violinist and musician, Isaac Stern. Stern, unlike almost any other musician I’ve known, had unique talents aside from that of master fiddler. I’m reminded of the story about two friends who bump into each other in front of Carnegie Hall.

First friend: I heard Isaac Stern here last night.

Second friend: Really. What did he say?

Stern was a great violinist but also an inspirational speaker, a promoter of young talent, and a major power broker in the music business. If Isaac Stern could not save Carnegie Hall, who could? Yet, as Francesconi described in vivid detail, when Stern threw himself whole-heartedly into saving Carnegie Hall, he was met with one roadblock after the other. We listened raptly as Francesconi told of a chance encounter of Stern’s that ultimately led to Carnegie Hall’s survival at the very last moment.

Francesconi’s tour led us everywhere—into one of the boxes with a breathtaking overview of the hall, onto the stage’s wings, into its new and gleaming office space and archives, and into the bowels of the hall where a single wall separates the sounds of great music from those of New York City’s subway cars.

Up to that point, I had been content to be a tourist trailing Gino Francesconi as he led us from one part of Carnegie to the next. But when we arrived in the area of the soloists’ dressing rooms, my tourist status abandoned me and my heart involuntarily beat a little faster. It was here, almost sixty years ago, that I had put on my concert clothes, practiced the thorniest passages in my chosen concerto one last time, and, both terrified and excited prepared to make my debut as soloist with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

Never in any other concert hall at any other time would I feel this way as I entered the stage. And how could it have been otherwise? Ever since my parents had taken me, age ten, to see director Edgar Ulmer’s film Carnegie Hall, featuring not only the hall itself but also a glittering array of artists such as violinist Jascha Heifetz, cellist Gregor Piatigorsky, pianist Arthur Rubinstein, and conductor Fritz Reiner, Carnegie Hall had lodged in my young brain as a distant but alluring goal, the ultimate certification that I was the real thing—a violinist, a musician, an artist.

Practice, my parents urged as I grew into my teenage years. Practice, I said to myself as I heard signs of improvement. That well-worn cliché had something to it. Someday I might get to Carnegie Hall.

When Francesconi’s brilliant tour of Carnegie Hall ended, we thanked him profusely and headed our separate ways into the city. Meanwhile, memories of my first performance in Carnegie had come vividly alive.

I remembered walking onto the stage, the hall seeming like a majestic ocean liner at dock, then seeing conductor Thomas Schippers giving the downbeat for Wieniawski’s Second Concerto in D Minor. I can only describe the orchestra sound that wafted across the footlights as I waited for my solo entrance as golden candlelight.

The hall, the sound, the music seemed to say to me, as it must have for so many others across the years: Play your very best. This is Carnegie Hall.

And I think I did.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

Enjoyed this article, Arnold!

Speaking of great violinists who have other talents… I just love your writing, thank you for sharing it with us!

Oh Arnold– you’ve done it again. What a tale! Filled with history and your inimitable, personal peeks, I so look forward to everyone. Even learning to sing in the key of Strawberry…

Thank you for all your wonderful music and sensitive writing. They seem to go hand in hand with you. What a joy to remember all the great times in Carnegie Hall!

Oh Arnold, what a beautiful moving story, masterfully told.

Reading you is a pure joy, full of discoveries, surprises. and unexpected turns, that keeps reverbrating long after reading it.

Thanks for it.

Hava

Thank you! Tchaikovsky’s diary of his American trip is a fascinating read. The one thing that consistently impressed him (in NYC, Baltimore, Washington, DC) was the indoor plumbing: running hot water!

I love your stories, Arnold! One question…..What was the chance encounter that Stern had that actually saved Carnegie Hall at the last minute??

What a heartwarming piece. I’ve just finished reading it in my local public library and found myself choking up each time another great name came up (Piatigorsky, Schippers, Stern, et al.). Your sharing of your experiences at CH are priceless; thank you for sharing them with the rest of your mortals. I’d think YOU might take up Isaac’s baton and save the Hall for the next generations. Keep writin’!

Hi Andrew Carnegie,

My name is Anuj Agarwal. I’m Founder of Feedspot.

I would like to personally congratulate you as your blog Andrew Carnegie has been selected by our panelist as one of the Top 100 Music Education Blogs on the web.

https://blog.feedspot.com/music_education_blogs/

I personally give you a high-five and want to thank you for your contribution to this world. This is the most comprehensive list of Top 100 Music Education Blogs on the internet and I’m honored to have you as part of this!

Also, you have the honor of displaying the badge on your blog.

Best,

Anuj

Definitely in the top 100! Congratulations, Arnold!

Enjoyed very much.

And I shared your story with my friends, it was too precious to read by myself.

Thank you for sharing your experience.

Leave a Comment

*/