Claude

March 6, 2018

How well can you really know a musician as a person based solely on his or her performance?

You might walk away from such an occasion with some sense of the musician’s intelligence, emotional depth, taste and style. But could you honestly say, despite the innermost thoughts and feelings communicated during the concert, that you now knew this person not only as a musician, but also as a human being?

I ask with the pianist Claude Frank in mind. Claude, a dear friend and colleague of mine, passed away on December 27, 2014.

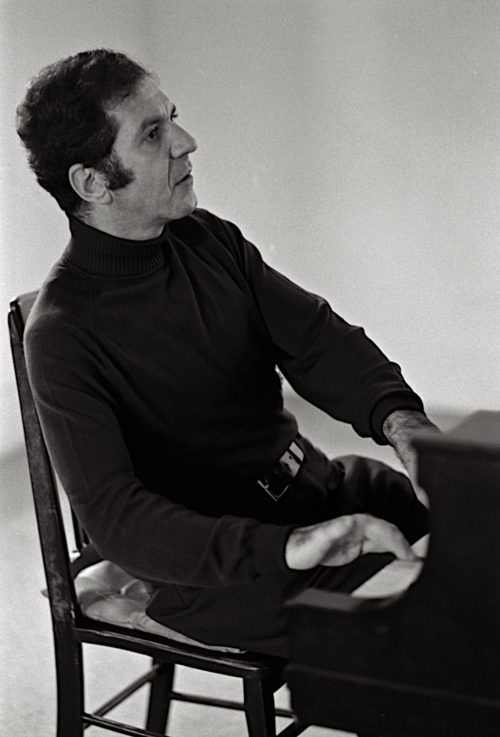

Photo © Dorothea von Haeften

Those of us who have heard Claude Frank in concert are the lucky ones.

Claude played with all the attributes we dream of in a pianist—technical mastery, depth of feeling, and soaring imagination. Listening to him from the audience or having personally performed with him on stage, I was inevitably swept away by the sheer suppleness, naturalness, and sensitivity of his phrasing. Even at the advanced age of eighty-five, as witnessed by the CD Claude made at that moment in time, his interpretation of works by Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, and Schumann was masterful. Claude always strove to ferret out the essence of music rather than to advertise his ample technical gifts.

And one more thing: As a string player myself, I greatly admired and appreciated his sensitivity to balance. Claude truly understood string players and allowed us the ability to shine unencumbered when music called for it.

In short, Claude Frank was a musician’s musician.

Here’s another question: Can you tell something of a musician’s true nature by his or her comportment on stage? In the case of Claude Frank, there was no playing to the audience, no theatrical gestures, no agonized facial expressions or head tossing, no gyrating choreography as he played. Claude walked on stage, bowed in a dignified manner, sat down at the piano unceremoniously, and began playing with a minimum of fuss.

Based on what one saw and heard of this great musician on stage, a listener might conclude that Claude Frank was serious to a fault, almost monkish in the way he might live, and with an ego devoted solely to the service of music.

Oh, how wrong that listener would be.

Dear music lover: For your information, Claude could gleefully tell the most bawdy jokes, followed by the dirtiest laugh I’ve ever heard. Claude could spin a yarn with the theatrical impact of an accomplished actor. Claude could pull off the most outlandish practical jokes. Claude could…

But why prattle on when I can offer you some delicious examples:

1. Claude and I once ran into each other after teaching at the Curtis Institute of Music. Claude made the mistake of asking how I was, and after listening to me complain about my all too busy life, how much traveling I was doing, and how little time I had for my family, he offered a suggestion:

“Cancel Curtis,” he said.

“Claude, I can’t cancel Curtis. My students depend on me.”

“Your students are some of the most gifted in the world. They’ll survive with one or two fewer lessons from you.”

When Claude sensed that his advice had made little impact on me, he went on to another subject and I completely forgot about the conversation. Several weeks later, however, I received an envelope in the mail without a return address. When I opened it, there was no letter inside and for a brief moment the envelope seemed to be completely empty. But on closer examination, I discovered two small pieces of paper, each apparently carefully cut out of different newspapers. At first, the printed letters on each made no sense when I attempted to match them together, but after several tries their message suddenly became crystal clear.

With a start, I read “Cancel Curtis.”

2. Perhaps one of Claude’s least favorite people was the conductor Herbert von Karajan. It was not only that Karajan had played footsies with the Nazis to jumpstart his young career. Claude was also bothered by the seemingly endless self-promotion and feverish adoration of the man. Claude was to perform in Salzburg, Austria, but the moment he stepped from the plane into the airport itself, he was surrounded on every conceivable surface by portraits of Karajan. Once again while waiting for his luggage, Claude could not escape larger than life images of the conductor everywhere. Then, when leaving the airport by taxi, Claude discovered to his dismay that both sides of the airport exit were festooned with giant posters of Karajan.

Enough, Claude must have thought. He decided to have some wicked fun with the driver.

“Tell me,” Claude asked in his native German, “who is this guy whose image I see plastered everywhere along the road?”

“What?” responded the astonished driver. “You do not know who this is, the great Herbert von Karajan? You’re certainly no music lover.”

“On the contrary, I love music,” said Claude, warming to the game he was playing, “but I’ve never heard of Karajan.”

Now visibly upset, the driver strove to end the conversation once and for all. “You may love music, sir, but you obviously know nothing about conductors.”

“But I do.” said Claude, now feigning thoughtfulness. “Let’s see now. There’s Arturo Toscanini, Otto Klemperer, Willem Mengelberg, Fritz Busch, Wilhelm Furtwängler, Karl Böhm, Leonard Bernstein, Antal Dorati, Leopold Stokowski, Herbert Tennstedt, Carl Maria Giulini, and George Sell. But Herbert von Karajan? No, I’ve never heard of him.”

The poor taxi driver almost drove off the road.

3. It was going to be opening night at the Met for one of Claude’s most beloved Mozart operas. His wife, Lillian, had been responsible for obtaining tickets, but unfortunately, she came back empty-handed. That night’s performance was completely sold out. Claude received the bad news silently for only a brief moment and then said to Lillian quite firmly:

“We are going to the opera tonight.”

“But we can’t,” responded Lillian, puzzled, “it’s sold out.”

“Nonetheless, we are going to the opera. Slip into your gown while I get my tux. Then put the champagne on ice and I’ll get the glasses.”

With this done, Claude put on his favorite recording of the Mozart opera they would have otherwise heard live, and sat on the sofa next to Lillian, both now formally dressed. They listened intently to Mozart’s miraculous music just as they would have at the Met. During both the first and second intermissions, Claude and Lillian drank flutes of champagne just as they would have at the Met. And when the performance ended, Claude applauded enthusiastically and even shouted, “Bravo,” just as he would have at the Met.

Claude and Lillian must have gone to bed that night every bit as uplifted as those attending the Met’s live performance.

How does one come to terms with the seemingly disparate qualities of Claude Frank the musician, with Claude Frank the person? With the oh-so-dignified Claude on stage and the impish and freewheeling Claude after he’s left the concert hall? And have the two Claudes ever managed to merge into one?

To my mind, some kind of answer lies in, of all surprising places, “Song of Love,” the 1947 film about the life of the composer Robert Schumann. The film starred Paul Henreid as Schumann, Katharine Hepburn as his wife, Clara, Robert Walker as Johannes Brahms, and Henry Daniell as Franz Liszt.

My parents took me to see “Song of Love” when it first came out. I was ten years old at the time and already playing the violin. Mom and Dad probably hoped that Schumann’s life story would be educational, even inspirational, but I found the film downright scary. Yes, Robert Schumann’s music touched me even at that young age, but the incessant ringing in his ears and the emotional turmoil that beset him were too much for me to bear.

That all changed when as an adult, I once again saw “Song of Love” quite by chance on TV. Scary? Absolutely not. Corny? Oh my! Despite Schumann’s sublime music and the way his poignant life was played out during the course of the film, I couldn’t help guffawing at the trite and overly sentimental lines served up. This was a film I never imagined wanting to see again.

That is, until one night at the Marlboro Music Festival many years ago, when it was announced that Claude Frank would perform “Song of Love” at the piano after dinner. We all flocked into the dining hall out of curiosity. What on earth was Claude up to? Claude strode to the piano in his usual sober concert mode, announced the title of the film, “Song of Love,” named its principal roles and actors, and then proceeded basically to perform the entire film?music, dialogue, the works. His performance was brilliant, and wildly funny.

We roared with laughter as Claude assumed each personality in voice and character. And yet, there was something unsettling in this masterful spoof of the film. It was not only the miracle of Schumann’s music and his tragic life story that Claude managed to insinuate into the comedy, but also a very personal glimpse into Claude himself, the human being.

There is a moment early on in Claude’s rendition of “Song of Love” in which, after a dramatic run-in with her father over which encore to play, young Clara announces in a breathless voice: “Ladies and gentleman, today as an encore, I’d like to play a piece by a new composer, Robert Schumann. The piece is called Traümerei.”

Photo © Dorothea von Haeften

Claude had set the scene well by infusing a quiet yet forceful determination in the way Clara delivers those lines, Then, he followed by playing a portion of Traümerei. Suddenly, and unexpectedly, the hilarious parody vanished and we were left with both Claude’s artistry and his humanity as he played one of music’s most moving works.

Undoubtedly, Claude’s wife, Lillian, and his daughter, Pamela, know him on a deeper level than we outsiders can ever hope for. But at that moment as Traümerei came to its hushed end, I had the unforgettable sense that the two Claudes had become one, that as Claude managed in the course of his riotous performance to show us the miracle of Robert Schumann’s music, he had also revealed much about himself.

Claude, wherever you are, I apologize for not having cancelled Curtis. You were right, of course. My students can do just fine with less of me. Now that you are gone, however, I find it difficult to do without you?you, the artist, you, the human being, and let me also add this: you, the cut-up.

Below is one of the dozens of Claude Frank’s performances of “Song of Love,” both unprofessionally filmed, but both still worth hearing and seeing.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

Dear Arnold,

Thanks so much for this. I need to add something of my own. In the first year I worked at Chamber Music America, we honored the Guarneri SQ at our annual banquet. Claude Frank was one of the speakers. None of us expected that his speech would be hilarious and irreverent, as he lampooned everyone from Casals to Sasha Schneider, with anecdotes of the times he first knew the GSQ at Marlboro.

I was doubled over with laughter, tears streaming from my eyes. The next day I asked the Conference organizer, David Ezer, whether he had picked Claude because he was so marvelous–and funny–a speaker. “I’d no idea,” said David.

I felt that Victor Borge, and maybe Groucho Marx, had been eclipsed.

And just a week ago, I heard a performance of the Mendelssohn Viola Quintet, with Pam Frank on first violin. She played wonderfully–but what struck me most movingly of all was her facial resemblance to her father.

Thank you for a beautiful tribute!

Unfortunately I never got to meet Mr. Frank but I clearly remember that he was regarded with high reverence among the musical community when I studied in the States in the 1980’s. Apropos of opera: I did meet Pam in Santa Barbara in the summer of 1983, though. She passed on her part in the production of Don Giovanni (in which she did not wish to participate) to me. It turned out into 10 days of absolute musical bliss. I will always be grateful to her for granting me that opportunity, particularly as I have never performed Don Giovanni since.

Just wanted to say hello and tell you how I have really enjoyed your great musical stories. for years now!!!! best of luck on your move to Santa Fe.

Thank you for a beautiful tribute.

Unfortunately I never met Mr. Frank, but I remember he was regarded with very high reverence by the music community when I studied in the US in the 1980s.

Apropos of opera, I did meet Pam in Santa Barbara in the summer of 1983. She passed on to me her part in the production of Don Giovanni, in which she did not wish to take part. It turned into ten days of utter musical bliss. I will always be grateful to her for giving me that opportunity, particularly as I have never played Don Giovanni since.

Leave a Comment

*/