Talent

September 1, 2014

Ninety-seven young violinists showed up at the Curtis Institute of Music’s annual violin auditions last spring with the hopes of becoming students at the school next fall. Thirteen made the semifinal round and of those, five were chosen by us, the violin faculty. Some who auditioned were still diamonds in the rough. Others already played solidly. But many played with great musicality and personality. It was difficult and even painful to have to admit only five candidates to the school when so many more were deserving.

I had to wonder what kind of journey each of these young people was taking in the hope of becoming, for want of a better word, a musician. For those diamonds in the rough, the immediate answer had to be: keep on practicing. For those who played merely solidly, more practice was certainly needed, but also an ongoing exposure to music’s intricacies and its magic.

But what about those young violinists who have had the very best teachers, have put in the countless hours of practice, and were at a high enough level to be looking for the elusive key that might turn them into artists? How did they get to where they are now? What’s next for them? And would their journey resemble in any way the one that I have been taking?

That journey for all of us must have started with the recognition soon after picking up a violin for the first time that we had talent, a vague yet encouraging word. I have no recollection of my first teacher, Mr. Singer, but he apparently told my parents that I had that elusive quality. My wise teachers patiently taught me the basics of the instrument and of music. I practiced, I improved, and why not? I had talent, as everyone continued to say. And then, most fortunately, I was admitted as a student to the Curtis Institute of Music.

It wasn’t as if I hadn’t thought earnestly about music up to that point, but much of my playing had been done with the aid of another word for talent: instinct. Dad, listening at home to me practice a particularly emotion-laden passage of music, would sometimes call out from his desk in another room, “Break my heart when you play that.”

And so I would rummage around inside myself without knowing exactly what I was doing and try to break Dad’s heart. I was relying on what lay buried and mostly untapped in me—the musical gift handed down through no effort of my own from my parents and their parents and then their parents.

At Curtis, I quickly learned that talent, whatever that might be, could only take me so far. I was expected to learn about music in a way that I had never seriously dealt with before: its overall structure, its specific styles, its history, and its details, all the way down to the smallest melodic fragment.

Sheer talent took a further backseat as I began to realize that my most important task as an interpreter of music was getting to know the inner workings of, say, Johann Sebastian Bach’s Chaconne for solo violin as he might have conceived it. In a perfect world, I would become Bach himself, think and feel as he did, and visualize the blueprint he had drawn up in his mind as he set out to write his mighty Chaconne.

You could call it an out-of-body experience in order to enter someone else’s.

But I wasn’t Bach. I was someone named Steinhardt, and with that came the need for an in-body experience. If I were to play the Chaconne with any success, there were questions to be answered. Who was I in relation to this music? How did it affect me? What could I bring to it that was personal? And how could I learn to cast aside inhibitions in order to access my deepest feelings and thoughts about it?

This was as much a psychological as a musical exploration, and in undertaking it, all the knowledge and experience I had gleaned in and after school served me well but only so far. To this very day, if I’m looking for a movement’s perfect tempo, for the just right ritard to end a passage, or for a way to let a phrase take wing and soar, I still find myself drawing on, even sometimes depending on that mysterious gift passed on to me through my genes, my instincts, my talent, and long ago through my ancestors.

Who were those ancestors who endowed both my brother Victor and me with enough musical ability to become professional musicians? Our parents were not musicians but they loved music. On one of their first dates Dad took Mom to Carnegie Hall to hear the violinist Yehudi Menuhin. Victor and I grew up hearing music in the house, being taken to concerts, and encouraged to study music. Clearly, our parents were a significant source of our talent.

Pearl and Mischa Steinhardt, Arnold’s parents, 1925

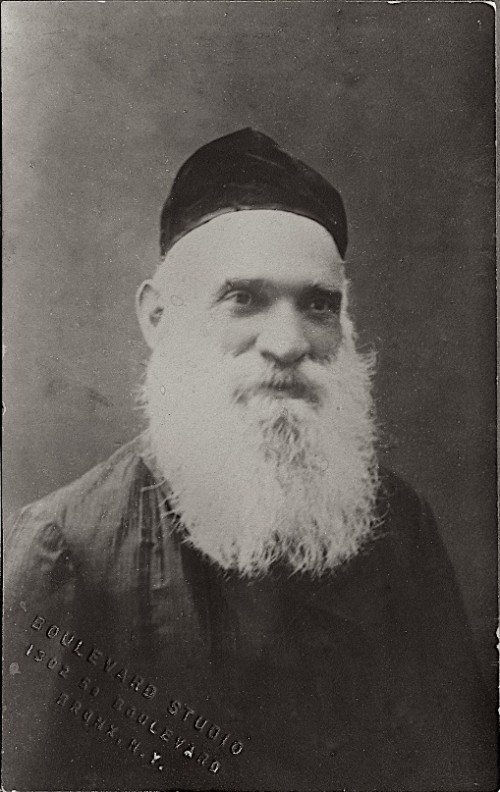

Going back in time, the musical trail inevitably gets thinner, but two people stand out. Yankele Goldberg, my maternal great-grandfather, was a Chasidic Jew who was known around his shtetl as the “oilman.” Yankele had four horses in his backyard, which went around and around pulling a millstone that ground seeds into oil that he then sold to the villagers. But Yankele apparently had musical talent. Mother told me that she loved sitting at the dinner table listening to Yankele sing praises to God in a lovely and affecting voice.

Yankele Goldberg, Arnold’s great grand father, c. 1910

Aaron Steinhardt, my paternal grandfather, was a businessman by profession with no musical training whatsoever but with a need to make up songs that he would endlessly sing around the house. Our father learned many of those songs and often sang one of them as Victor and I were growing up. That song, now easily well more than a hundred years old and less than a minute long, has been handed down from generation to generation as a part of our family history. It is something Victor and I cherish both as music and as a lone artifact of our genetic makeup. Several years ago, Victor was inspired to write Fantasy on an Ancestral Melody, a work based on our grandfather’s song.

Aaron Steinhardt, Arnold’s grandfather, c. 1914

I did not know Yankele Goldberg or Aaron Steinhardt. They passed away long before I was born. But, dear Great-Grandpa Yankele and dear Grandpa Aaron (dare I be that familiar?), I raise a glass to you both in gratitude and thankfulness for the musical talent you have handed down to me. And for you, Grandpa Aaron, I also raise my violin and bow to play your song.

Video copyright Dorothea von Haeften

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

This one brought tears to me eyes….

I loved this entry! Thank you to Victor and to you for providing the wonderful link from your past to the present. Without words, so much has been said.

thank you maestro Steinhardt. What a beautiful way to explain that family is everything behind talented people . I love the song, it melted my heart into tears of joy!!! I remember my grandfather making his own violin, and playing Colombian music on it when I was 5 years old. Family is everything!!!

So affecting, Arnold. You go right to the basics; what’s really there on the page and who’s behind that bunch of squiggles, how can I better realize the composer’s message to the world. And, most importantly, from where came those precious genes that caused me to become a musician. My mother played her Viennese waltzes with much love in the right hand, but with less accuracy in the left. Maybe that’s why I ended up playing the viola, where we find so much of the harmony, and thereby correcting her few errant wrong notes. Bernie, to the rescue!

Just lovely. The video clip was especially haunting. A grand legacy for future generations of Steinhardts’.

Thank you for the wonderful story of your musical heritage and for so beautifully playing your grandfather’s song.

Oh Arnold– you succeeded in your father’s request tp “break my heart”. Not only trough the beauty, the originality and the musicality shown in Grandpa (may I call him Zaide?)Aaron’s melody but in the fact that his grandson understood it so well and gave it such life as he himself must have imagined. I love your Strawberry blogs. Keep them coming!

Love Sonya

Inspired and magical, dear Arnold. Quite apart from the music–well, not entirely apart–you write like an angel.

I, also, always look forward to the next Strawberry! Keep them flowing, please.

The backward-viewing we engage in, trying to grasp our ancestral origins, is just about as deeply moving any inquiry can be. The musical thread makes it all the more exquisite. Bringing forward this little song through the generations is a very pure form of love. Bravo!

Dear Arnold

So very touching. The beauty of your soul is evident in both you playing and writing. Thank you from the bottom of my heart. Your highschool friend Arianne

So, this is how it was born your talent!!!

Love, Maru

Leave a Comment

*/