The Bartók Project

July 7, 2017

When I was still a teenager, a friend coaxed me into a record store with the sole purpose of having me listen to something he considered of utmost importance. In those days, every record on sale had a sample that one could hear in a private booth. My friend refused to divulge anything as he set the record in motion. “Just listen,” he said, in a low, conspiratorial voice that seemed to imply a clandestine plan for world revolution.

A series of repeated notes—insistent, disjointed, and urgently clamoring for attention as if in some kind of secret coded language—filled the booth. Then the music burst forth in folklike exuberance, eerie dissonances, invocations of natural sounds, and lilting dance rhythms. As the work approached its end some five movements later, a simple children’s tune appeared out of nowhere, proceeded to go off the tracks in wrong-note confusion, and finally recovered in a rush to the music’s exultant conclusion.

What kind of music was this? I could not fully grasp its intent, and yet I knew without a doubt that I was listening to something utterly new and of enormous emotional impact.

The work was Béla Bartók’s Fifth String Quartet.

I thought of this, my first encounter with a Bartók string quartet, while waiting at the Curtis Institute of Music for a student recital to begin—but not just any recital. The program consisted of all six Bartók string quartets.

Composers don’t necessarily devote the major portion of their adult lives to writing string quartets. For example, Richard Wagner, Gustav Mahler, and Richard Strauss wrote none, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel only one, and Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms each a total of three. But for several, including such musical giants as Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Schubert, Felix Mendelssohn, Antonín Dvo?ák, and Dmitri Shostakovich, the string quartet must have had enduring significance, for they returned over and over to this most intimate of art forms. Béla Bartók belonged to this exclusive club with his six quartets written over a period of thirty years from 1909 to 1939, and with sketches for a seventh already on paper at his death in 1945.

A concert featuring string quartet music of only one composer can be problematic. An all-Brahms program? Quite heavy. All-Shostokovich? Rather depressing. All-Mozart? Almost too much beauty for one sitting. But all-Bartók? Our Guarneri String Quartet, having performed the Bartók quartets many times and even recorded them, was finally cajoled into playing all six with only a large intermission separating them. Walking off the stage at concert’s end, the four of us were in agreement: Each quartet was a masterpiece, each was entitled to a place of honor in any program, but as far as all six performed together? Some of the qualities that made every one of the quartets so compelling—complex rhythms, arresting dissonances, exotic effects—tended to become oppressive when grouped together. We never played all the Bartóks in one concert again.

That being said, I looked forward to this particular Bartók string quartet concert at Curtis for several reasons. As one of the group’s faculty coaches, I had witnessed over a period of many months some inexperienced students successfully put their arms, brains, and hearts around enormously challenging music. That vaunted moment of truth—the actual performance itself—was about to take place in which we would hear the fruits of their labors. This time, however, the students had been given an additional concert task. Each had been asked to research a particular aspect of the music and to speak about it briefly to the audience directly before their performance.

Conductor Jonathan Coopersmith, and violist Steven Tenenbom, both on the Curtis faculty, had come up with this remarkable Bartók project. Steve, also one of the groups’ coaches, drew on his vast experience as a member of the distinguished Orion String Quartet, while Jonathan helped prepare the students’ speaking presentations as well as providing feedback on historical and theoretical ideas.

Jonathan and Steve’s vision extended beyond the music itself. For one, the audience seats were set up to encircle the quartet players. There would be no front, back or sideways to this concert. Steve and Jonathan also included a lighthearted touch intended to counteract the weight and intensity of Bartók’s music. Two intermissions were to break up this Bartók marathon, with pizza served during the first and a cake displaying Bartók’s face in the second. Both performers and audience were invited to attend, eat, and mingle.

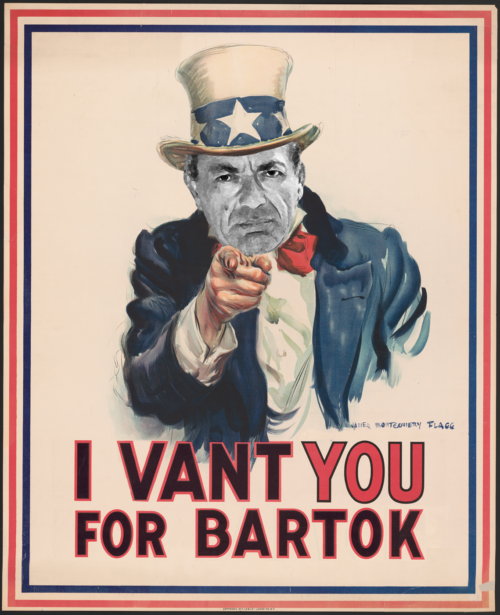

I had arrived at the concert early. With time to kill, my mind wandered back to my own first performing experience with the Bartók quartets in 1959 at the Marlboro Music Festival. Alexander (Sacha) Schneider, second violinist of the renowned Budapest Quartet, and a charismatic and enormously influential musician, came for me and two other young musicians looking like that old United States Army recruiting poster of Uncle Sam pointing his finger— and in this case speaking with a Russian accent. “I vant you,” Sacha ordered, “to perform Bartók’s Second String Quartet in four days from now.” We gasped. None of us had ever played this work of constantly changing meter and complex rhythms.

Uncle Sacha vants you.

Sacha, who knew the work intimately, used his second-violin seat as a command post during rehearsals. He guided us through the thorny passages, instructed us in optimum tempos, and suggested crucial changes in nuance and mood. The learning process that would have taken us weeks if not months was compressed into mere days.

This was hardly democratic music-making and yet, I’m grateful to Sacha, benign dictator that he was. I walked offstage after our Bartók performance profoundly moved if slightly overwhelmed by the Quartet’s dreamlike first movement, its rambunctious and whirlwind second, and its final movement filled with unflinching despair and capped by two mournful plucked chords that felt like the last nails in someone’s coffin. Without really knowing it at the time, this powerful Bartók experience involving simply four likeminded voices began to inch me toward my musical future.

Only five years later, in 1964, four of us formed the Guarneri String Quartet at Marlboro.

Fortunately, the Curtis project took place over several months rather than the four days in which Sacha force-fed Bartók’s music to us innocents at Marlboro. I prefer to think of the Curtis coaches as string quartet whisperers rather than benign dictators. We suggested rather than demanded, and then, in truly democratic fashion, rehearsals would follow without us. Often, our suggestions were adopted, but equally often, students came up with their own ideas that surprised and educated me, the so-called wise elder.

My reverie was broken by applause. Four young musicians made their way to center stage, one by one they spoke articulately about Bartók and his music, and then they sat down to perform Bartók’s String Quartet No. 1.

I must confess a certain amount of anxiety as bows descended on strings. A performance by young, inexperienced musicians confronted with Bartók’s monumental challenges can easily crash and burn. Ensemble can go astray, musical focus vanish, and let’s not forget how easy it is to simply lose one’s place in Bartók’s rhythmic labyrinths.

I have often wished that first performances could be outlawed entirely. Then we musicians could go directly to the second performance when nerves had somewhat dissipated and unruly difficulties smoothed out.

The Curtis performances of all six quartets did not crash and burn. Far from it! I was amazed at not only the technical polish but also the sense of emotional range and intensity coming from each group. These performances were undoubtedly milestones for the Curtis students that they would treasure and carry with them forever, just as my early experiences with the quartets came flooding back to me as I waited for their concert to begin.

Bartók began composing his sixth and last string quartet in 1939, just as World War Two had broken out and as his beloved mother lay dying. Each movement begins slowly and sadly, but Bartók abandoned his original idea for a quick folklike last movement of Romanian character. He replaced it with one that was slow and of deeply penetrating sadness. The quartet ends with the cello gently strumming for one last time the first notes that begin each movement—an unforgettable moment of despair and resignation.

Béla Bartók left Europe when he saw the Nazis approaching. He wrote to a friend, “If someone stays on here, when he could leave, he can thereby be said to acquiesce tacitly in everything that is happening here.” Bartók never returned to Hungary, his homeland.

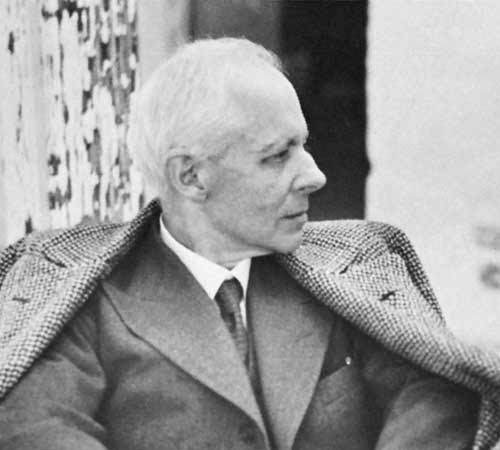

Béla Bartók

As moving as the ending of Bartók’s Sixth Quartet inevitably is, and certainly as played by these gifted Curtis students, it has taken on added significance for me. At the Guarneri String Quartet’s very last performance after a forty-five-year concert career, we played that final Bartók movement as an encore. I was surprised and touched when the Curtis group’s cellist chose to mention this before their own performance.

Would I ever want to attend a traditional all-Bartók string quartet concert? As much as I love the quartets, probably not. Would I ever again want to attend an all-Bartók event as presented in this manner by the Curtis Institute of Music? Definitely. For both students and audience, and for Béla Bartók’s compelling music, this was a concert to be cherished and remembered.

Also, the pizza and cake were delicious.

STUDENTS:

Quartet No. 1, Op. 7

Shannon Lee, violin

Jenny Yeycong Jin, violin

Julian Tello Jr., viola

Arlen Hlusko, cello

Quartet No. 2, Op. 17

Brandon Garbot, violin

Grace Clifford, violin

En-Chi Cheng, viola

Timotheos Petrin, cello

Quartet No. 3

Stephen Tavani, violin

Youjin Lee, violin

Michael Casimir, viola

Joshua Halpern, cello

Quartet No. 4

Zorá String Quartet

Dechopol Kowintaweewat, violin

Seula Lee, violin

Pablo Muñoz Salido, viola

Zizai Ning, cello

Quartet No. 5

Abigail Fayette, violin

Lun Li, violin

Kunbo Xu, viola

Zachary Mowitz, cello

Quartet No. 6

Hyun Jae Lim, violin

Haram Kim, violin

Julian Tello Jr., viola

Albert Seo, cello

COACHES:

Shmuel Ashkenasi

Arnold Steinhardt

Steven Tenenbom

Peter Wiley

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

In 1962 I was a freshman at what was then known as Harper College. During that year I was happily exposed to the Guarani Quartet. Now, near the end of my life, I am delighted to be introduced to your occasional reflections. Thank you across the years.

Your missives, when they hit my inbox, cause me to drop everything and immediately read. I was transported by your words to an event decades ago, and just recently. I can almost hear the performance you attended – and now I am pining for pizza, cake, and Bartok! Loved this. Thank you so much.

I just love this story. And the project too.

https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/?ui=2&ik=d62e3c4e84&view=att&th=124b5a7ac641846f&attid=0.1&disp=inline&realattid=file0&safe=1&zw

Amelia Island 2009 concert. I was delighted to be in the audience.

Thank you for all you do for Marlboro, Lake Champlain and other music venues.

My introduction to the Bartok quartets was at the hands of the New Hungarian Quartet and especially my teacher Denes Korimzay. They played a Bartok cycle at Oberlin College and I will never forget it. Your post brings back great memories! And I have heard you play almost all of the Barton’s at various concerts and it was truly a pleasure.

I enjoy reading your reflections and insights and would love to hear more on the subject of Democracy vs Dictatorship in the workings of a String Quartet

Wonderful story!

Back in early 1984 there was a similar arrangement at the Eastman School: all six quartets played in one evening by four student quartets that had been coached by the Cleveland Quartet. There was one intermission with Hungarian food being served. I remember I was so energized by the whole experience that I ran home to the dormitory afterwards.

I eventually learned and performed no. 4 at Charles Castleman’s wonderful Quartet Program in the summer of 1985. It has remained the only Bartók quartet I have performed.

Arnold,

I probably went to the same music store in Hollywood to listen to beautiful music.

I so love your music making, and now near the end of my life, I am so grateful that you and your music making has been part of my life.

Sitting with you, Arnold, for part of this incredible event truly enhanced the already beautiful experience. What a special day I will never forget! I venture to guess that one of the quartet members in particular – at age 13 – will also never forget. Imagine playing your first Bartok quartet at age 13… Thank you to all the coaches, kudos to all of these amazing young people and bravo to Steven Tenenbom, who conceived the project.

This is a beautifully written and touching account perfectly balanced between your poignant recollections of the past, present moment and future hopes. Thank you for sharing.

I was at this concert! It will stick in my mind as one of the most memorable concerts I’ve ever attended–right up there with performances by Bernstein, Boulez, Kubelik, Solti, and the like!

And then there’s *your* recording of the 2nd! I remember acquiring the Guarneri set as a teen, right when it was released. I was already familiar with the quartets, but the 2nd was a closed book to me–until I heard your recording. You brought out the extent to which it is really a nineteenth-century piece–written, after all, at the end of the Long Nineteenth Century–and that drew me right in!

My first experience playing a Bartok quartet for an audience was also Bartok Second String Quartet, and it was with you, Arnold Steinhardt playing first violin!

January 1976, I went to the Cleveland Chamber Music Seminar as a cellist with my student quartet from Indiana University School of Music. The Guarneri String Quartet was in residency for a few days, to play a concert and do some coaching with the student groups. We were thrilled that we were scheduled to play the Bartok, which we had been working on, in a master class to be coached by Arnold Steinhardt. Three of us showed up at the appointed time, but unexpectedly our first violinist had become ill at the last minute, and could not make it. The local Cleveland TV news cameras were on hand to get some nice footage of The Guarneri coaching students for the eleven o’clock news. The stage was set, the audience was waiting, there we were with everything ready to go, but missing our first violinist!

What to do? Well, you were there too with your violin, and you suggested instead of coaching, how about you just sit in and play thru the Bartok with us as first violinist. And so it happened, for us it was a classic ‘fifteen minutes of fame’. Thank you again, 40+ years later, for that memorable first experience with Bartok.

Leave a Comment

*/