I Love You

June 2, 2017

Over the past few years, I’ve begun to depend more and more on my smart phone. At first it was just for telephoning, emails, and for taking photos. But more recently, I’ve begun using it for all kinds of useful things: weather reports, the news, messages, driving directions, as a metronome, playing scrabble, and even as an alarm clock. The smart phone is an absolute wonder.

The other night, I set the alarm clock on my phone utterly confident that it would wake me at the appointed time with its familiar beep, beep, beep. For some unfathomable reason, however, the beep, beep, beep never arrived. Instead, someone began playing the violin while I was still deep in sleep.

You might think that someone fiddling in my ear at that ungodly hour would be intrusive and unpleasant, but no, the violinist was playing with the sweetest, most alluring sound imaginable. Not only that, a full orchestra, including harp, accompanied the performance. For a brief moment, I thought I’d died and, despite some very questionable things I’ve done in my life, I had not gone to Hell after all.

Finally, unable to wrap my brain around the situation with eyes closed, I opened them. There was no violinist, no full orchestra, and no harp playing in my bedroom. The sound was coming from my smart phone.

Have you, by any chance, seen the film “2001, A Space Odyssey,” in which the computer, Hal9000, attempts to takes over the spaceship for nefarious reasons? I certainly had not knowingly changed the alarm sound on my smart phone. Had the phone, perhaps inspired by its mentor, Hal9000, decided on its own to change the wake up call from “beep” to “violin”?

But never mind what my smart phone did or did not do. For the moment, the intoxicating sound of a violin filled my bedroom, and not with just any kind of sound. Like hemlines, tie widths, and hair length, styles in playing inevitably change. From the violinist’s satiny sound and shimmering vibrato, anyone in my world of string playing would tell you that this was not the clean, more literal fiddler often heard today, nor was it one of those now quirky and mannered-sounding violinists from the very early years of the 20th century.

This violinist played with a kind of throbbing warmth that I instantly recognized. It was what I always think of as the “I Love You” school of violin playing. You’ve heard it countless times in those romantic movies of the 1940s and 50s, possibly without even realizing it. The star-crossed lovers are about to express their love for one another, but they don’t really have to. We in the audience know exactly how they feel because a violin is playing softly but ever so emotively in the background. That sound—tender, intimate, personal—says, “I love you,” better than words ever could.

The violinists capable of providing those few seductive bars of music at just the right moment in a movie’s love scene were members of a very exclusive club. All were distinguished musicians whose names I heard bandied about when I was growing up in Los Angeles. One of them, Toscha Seidel, concertmaster at Paramount Studios, was my teacher for several years. When he demonstrated a musical passage during my lessons, his sound was like rich chocolate, his vibrato like a wildly beating heart. It was “I love you” playing.

I did not know the violinist playing on my smart phone, and for the moment, not the music as well. The lushly orchestrated score flowed forward in some kind of extended introductory mode, hesitated briefly, and then the violinist played a long F natural followed by the B flat above. With that unadorned and commonplace interval, my pulse quickened a little, for those two notes somehow told me exactly what the music was: All the Things You Are, a song written in 1939 by Jerome Kern with lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II. The song is beloved by both singers and jazz musicians for its breathtaking beauty and for its surprising harmonic twists and turns.

I listened, transfixed, to All the Things You Are, a song I’ve loved for as long as I can remember. The unnamed violinist seemed more singer than instrumentalist as he glided through a series of gently rising intervals and their poignant repeat in a surprising new key. His playing was tender and confiding as the music moved on with an exotic journey through an array of unexpected keys. And then, he played the beginning melody’s reprise with an aching sweetness, as if it were the ultimate expression of the song’s message: All the things you are.

Even on my phone’s tiny speakers, the violinist’s performance commanded attention. I had to listen again. And then once again, but this last time with a glimmer of recognition beginning to coalesce in my ear. I knew that sound. I knew that particular suppleness of phrasing, that one-of-a-kind way of slipping vocally from one note to another. Years ago, I had downloaded an entire record of playing by such a magical violinist, and yes, he had recorded All the Things You Are along with a host of virtuoso show pieces. To confirm my suspicions, I listened to the recording, Echoes and Encores, once again. The mystery violinist who awakened me so deliciously that morning had been unmasked. He was Erno Neufeld.

Erno Neufeld died on January 14, 2006 at the age of 96. His Los Angeles Times obituary stated that “He was considered a world class violinist by his peers, a term usually reserved for well-known concertizing artists. However, in this case it was bestowed on a virtually anonymous musician who was heard as a soloist on hundreds of the most prestigious motion picture sound tracks and phonograph recordings in the history of the entertainment industry.”

I did not have the good fortune to know Erno Neufeld, but his son, John, graciously supplied me with some biographical information. Neufeld, born in Hungary, had his first violin lesson from his grandfather, a cantor, followed by lessons from a trumpet player, a cellist, and only then an actual violinist. Eventually, he studied at the Franz Liszt Academy with the esteemed violinist, composer, and teacher, Jenő Hubay. Upon graduation, he was heard by Joseph Hoffman, who offered him a full scholarship at the Curtis Institute of Music. However, his study there with the eminent violin teacher Carl Flesch, only lasted for a year. Neufeld was forced to go to work with pit orchestras in New York in order to help support his family in Europe. Ultimately, he set out for Hollywood where he established himself as concertmaster at Republic Studios, then the Armed Forces Radio Services, at Universal Studios, and finally as a freelance concertmaster in a wide variety of motion picture studio orchestras. Erno Neufeld retired at the age of 78.

The Hungarian concert violinist Joseph Szigeti, (at one time my violin teacher) had also studied with Jenő Hubay at the Liszt Conservatory some years before Neufeld. Both began their careers focused on the brilliant virtuoso repertoire. Each can be heard on recordings to be found on the internet—Szigeti on YouTube, Neufeld on his Echoes and Encores album—both playing The Zephyr, a charming encore morsel composed by their teacher, Hubay. Their styles are markedly different, but both Neufeld and Szigeti display dazzling virtuosity and soaring lyricism.

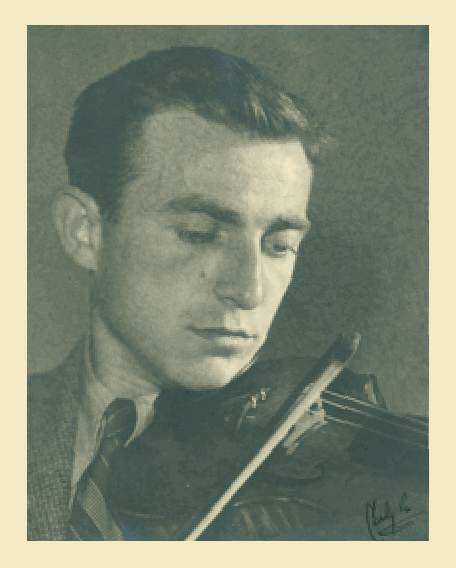

Erno Neufeld

Perhaps Neufeld accomplished all he had dreamed of as a professional musician playing anonymously in Hollywood, but I cannot help wondering about that juncture in his young life when he was forced to leave the Curtis Institute of Music. What if he had been able to stay? What if he had blossomed into a different kind of musician at Curtis—a school with some of the world’s foremost artist-teachers. What if he had then become an internationally known and admired concert violinist like his countryman Joseph Szigeti?

At the very least, what if Erno Neufeld’s name could have been put up on the marquee along side the names of those glamorous movie stars he so brilliantly accompanied?

Unfortunately, these are the kind of “what if” questions even my smart phone cannot answer.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

How can a connoisseur of ” I Love You” violin playing get that alarm tone???? No joke! Would do anything to hear it!

Thank you for this beautifully written piece.

I went right to YouTube to listen to Szigeti play the Zephyr- exquisite! Hope to hear the Neufeld album some day. Thanks for telling his story. When you wondered what if he had received billing for his performances, I was reminded of the late, great Marni Nixon, who dubbed for Natalie Wood in West Side Story, and Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady, among others, with never any credit to be found.

This reminds me of the great David Nadien. He was, for a short while, concertmaster of the NY Philharmonic, but worked as a studio musician most of his life. a wondrous violinist!

Thank you for this fine piece of writing-up to your usual (high) standards.

Another heartwarming(heartbreaking?) story from the master. I love you!

Thanks for this, as always. Whenever I’m watching old movies on TCM, I am noting the soundtrack and wondering which violinist I am listening to. You’ve added to my list of unsung Southern California virtuosi.

Your writing is a bit of I love you too. It always makes me smile and reminds me of what a fine person you are. If there is a heaven, you will definitely be there welcoming your friends with your fiddle.

I love this soooooo much… Thank you from the bottom of my heart for sharing!!!

Lieber Arnold,

das ist eine ganz wunderbare und zu Herzen gehende Geschichte. Sie bewegt mich vor allem, weil ich dabei intensiv an Dich denke. Es ist so schade, daß wir uns nie sehen, nur hören. Neulich habe ich sehr aufmerksam und in Italien Beethoven-Quartette mit Guarneri gehört. Noch was: In “Violin dreams” schreibst Du nichts von Deinem Lehrer Toscha Seidel. Ich mß doch nach NY kommen, und wir müssen eine Flaache Bordeaux zusammen trinken. Dein Peter

Dear Arnold, sitting in NH.listening to my iPhone and reflecting on your unending capacity to make music even in your dreams. Another treasure. Thank you once more, with love. K

I love Anne Akiko Meyers playing Autumn in New York and Autumn leaves on her album ‘Seasons… Dreams…

Very interesting as always, and so nice to hear a bit about Szigeti. One of the great joys of my life was to know dear “Joska” as a friend. I met him by the chance of sharing the same birthday and we corresponded for many years–he invited me to his masterclasses in 1965 and later to dinner at his home in Switzerland and to his 80th birthday party at the Chateau de Chillon. Happy memories of not only a great musician but also a very kind gentleman.

Dear Arnold, this is so beautiful – and a perfect last line

An inspiration to all of us string players!

Dear Arnold. I’m a violist. Member of Met. Opera orchestra for 37 yrs. watching a movie Universal studios There was an incredible violin solo. I had to find out who it was and of course it was Erno. Neufeld. They don’t play that way anymore. There is electricity in that sound. One note from his violin playing is just wonderful. Rich and so much music in it. I listen to Echos a lot. I’m so happy to hear that you love him too.

Mr. Steinhardt, Hollywood had several other concertmasters with remarkable tones aside from Neufeld and Seidel. Anatol Kaminsky, Louis Kaufman, Lou Raderman and Harry Bluestone come to mind. Seidel recorded many solos for the film The Great Waltz which are astonishing.

had to google the fine violinist seen on an old jack benny program -neufeld. thanks for filling in the details and the appreciation

Erno Neufeld was my father’s cousin.

Do you know anything about his son John? What he does?

A great Hungarian violinist. He was the concertmaster for Henry Mancini’s orchestra, and I love that signature sound of his. That music inspired me to take up the violin and viola. Thank you for this article…and the photo.

Leave a Comment

*/