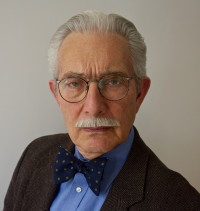

Music From Marlboro, the Fiftieth Anniversary

November 8, 2016

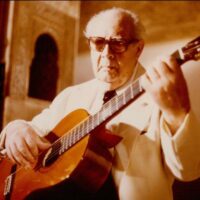

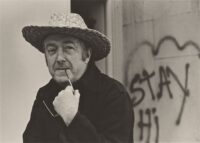

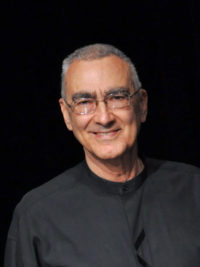

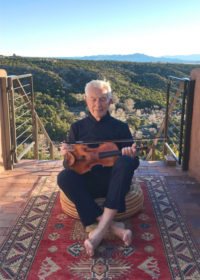

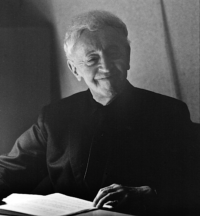

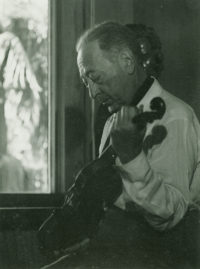

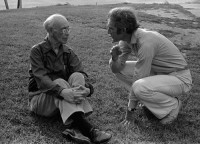

If anyone were to ask me what the single most significant musical influence of my life was, the answer would be unequivocal: The Marlboro Music School. In the many summers I spent there as a young adult, I was able to study, perform, and listen to the great chamber music repertoire shoulder to shoulder with some of the world’s most distinguished musicians. I was able work on the Schumann Piano Quintet with pianist Rudolf Serkin, the Debussy Flute, Harp, and Viola Trio with flutist Marcel Moise (who had given the first performance of the work under the tutelage of Debussy himself), Bartok’s Second String Quartet with violinist Alexander (Sasha) Schneider, a master class with the cellist Pablo Casals, and on and on.

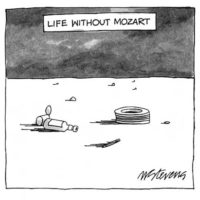

Chamber music offered me a wealth of musical inspiration. After all, what could be more enlivening, more substantive, more moving than a Schumann Piano Trio, a Mozart Two Viola Quintet , or Dvorak’s Serenade for Woodwinds, Cello and Double bass. But as someone old enough to have already learned his instrument well but young enough to be unsure of what music was and who I wanted to be as a musician, chamber music became my greatest teacher.

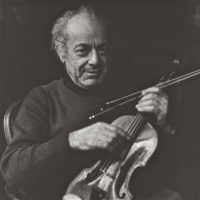

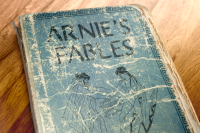

Felix Kuhner, second violinist of the Kolisch String Quartet that performed by memory, was once asked how he managed to play his part flawlessly without the benefit of notes. “I play the part I don’t hear” was his answer. With or without notes, that is the essence of chamber music. Know the entire work, it’s structure, it’s meaning, it’s details, in effect all its parts. And that was, loud and clear, Marlboro’s message, it’s challenge for me: become a complete musician.

Those giants of music at Marlboro who served as my mentors were invaluable, but so were the young, immensely gifted musicians of my own generation with whom I made music in countless groups and formations. They were the ones who challenged my ideas and who made me consider their own. With them, I slowly learned to accept criticism, to hand it out with respect, to retain my individual personality while joining in what was clearly a team effort.

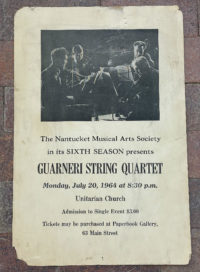

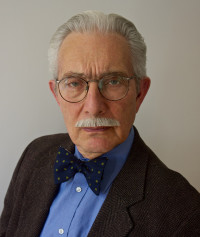

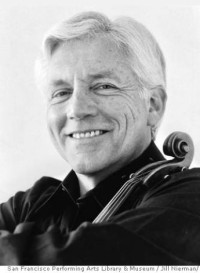

But almost without my realizing it at first, four of us at Marlboro, violinist John Dalley and violist Michael Tree, fellow students years earlier at the Curtis Institute of Music, cellist David Soyer and I began to slowly gravitate towards one another musically. Amongst other works, I played with David in a Brahms trio, with Michael in a work by Adolf Busch, and with John in the Schumann Piano Quintet. Finally, playing led to talk: wouldn’t it be a dream fulfilled to play string quartets together. And in 1964 we formed the Guarneri String Quartet at Marlboro. To celebrate, Rudolf Serkin brought a bottle of champagne and Sasha Schneider handed out lots of advice based on his own experience in the Budapest String Quartet. We had no concerts, no manager, and at that point not even a name, but it was the beginning of a career in which we performed on the world’s concert stages for the next forty-five years. This couldn’t and wouldn’t have happened without Marlboro- the great training ground for young musicians and as an unintended consequence, the great matchmaker that brought ours and many other groups that followed together.

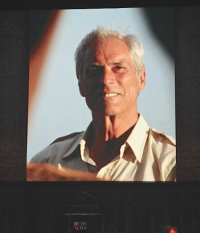

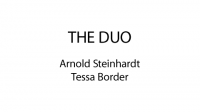

Not long after the Guarneri Quartet formed, Marlboro decided to showcase its music and musicians for the rest of the world to enjoy with Musicians From Marlboro. In 1965-66, its first season, one of the first touring groups featured another type of quartet consisting of Benita Valente, soprano, Harold (Buddy) Wright, clarinet, Peter Serkin, piano, and me, violin and viola. Our programs included the Mozart Kegelstatt Trio and songs, Schubert’s Shepherd On The Rock, the A Minor Violin Sonata, and the Bartok Contrasts.

They say that the quickest way to end a friendship is to go on a long trip together. That didn’t happen to our quartet as we made our way from Boston, to New York, to Philadelphia, to Washington, DC, and with stops in between. Yes, accommodations had to be made. Buddy willingly gave up his beloved cigars when we traveled by car together, and we tried to get Peter, still a teenager, more involved in the after concert parties by conducting quizzes the next day en route to that evening’s concert: What was the presenter’s wife’s name? How many children did they have? Describe the painting that hung behind the living room piano, Etc.

But the music was the thing, and in this respect we behaved as if we were back in Marlboro rehearsing, discussing, and experimenting in an effort to dig ever deeper into the programs’ exalted music even as we went from city to city.

One small musical detail stays with me after all these years concerning Mozart’s Kegelstatt Trio, K498, for Piano, Clarinet, and Viola. It is unquestionably an inspired work but certainly not a flashy one- and especially not it’s ending which seems to be fading away only to suddenly rise at the very last moment with three brusque chords that finish the Trio. Peter, Buddy, and I walked off the stage after the first performance shaking our heads. The modest ritard we had agreed on for the ending had turned out to be oh-so-bland. “Let’s make a big, gorgeous ritard tomorrow night”, one of us suggested. We nodded enthusiastically. This was going to be the ultimate solution to the ending problem. But the next night, we walked off the stage shaking our heads once again. The big, fat ritard had been just that: a big, fat ritard- over the top, obvious, and certainly unsuccessful. And just as suddenly as the first idea, came another: to finish the work absolutely in tempo- streamlined, no nonsense, direct, simple. This would be the perfect ending, at least so we thought. But it wasn’t. This time the ending felt unfinished and anticlimactic.

Night after night Peter, Buddy, and I tried different ideas for the ending of that Mozart Trio. It was challenging, amusing, maddening, sometimes even gratifying. I cannot recall if we were ever truly satisfied, but I suspect I remember this detail among so many from that tour for what it exemplified. Each of us was trying to play the part we didn’t hear, to search for the music’s very essence. In fact, that was and continues to be the very essence of Marlboro itself.

In 2007, over forty years later, I went on another Music From Marlboro tour- this time as the senior member in a group including Anna Polansky, piano, Lily Francis, violin, Wendy Law, cello, and Yu Jin, viola- four inspiring young musicians. Our program consisted of the Mozart Piano Trio in G Major, K496, Shostakovich 8th String Quartet, and Dvorak’s E Flat Piano Quartet. As we sat down to rehearse for the tour, I had already performed during past years both the Shostakovich and Dvorak dozens of times with our Guarneri quartet and with many pianists including the incomparable Arthur Rubinstein. Whatever knowledge and experience I had acquired from those concerts would go into the mix during rehearsals but equally, I would have to let past history recede enough for me to welcome the sounds and ideas coming from these immensely gifted young players.

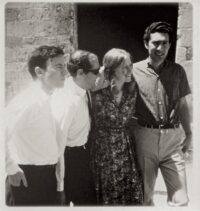

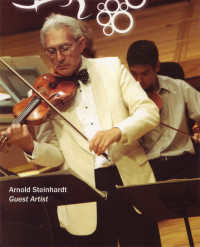

From left to right: Anna Polanski, Arnold Steinhardt, Lily Francis, and Wendy Law, directly after a Music From Marlboro rehearsal / Photo credit: Alan Cohen

As Anna, Wendy, Lily, Yu Jin, and I went from city to city, we continued to rehearse and critique our playing before concerts and sometimes afterwards over a glass of wine. How could we better capture the desperation of the Shostakovich quartet, the Dvorak’s lilting grace and joyfulness, and the majesty and good cheer of the Mozart Trio? There were so many viable choices available. At those moments, I was brought back 41 years to Peter, Buddy, and I struggling to find a successful ending to the Mozart’s Kegelstatt Trio. It seems that Marlboro had not changed that much over time and that it’s primary message remained loud and clear:

Play the part you don’t hear. Look for the music’s essence. Dig deeper.

My recollections are part of a marvelous and detailed booklet celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Marlboro touring program which can be found at marlboromusic.org.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

It’s nice to hear the late clarinetist Harold Wright spoken of here. I consider him the greatest clarinetist the US ever produced. May he not be forgotten. Thank you!

This is a wonderful remembrance/essay. But, ohhhh, with due respect, I wish the apostrophes on your frequent use of “its” were removed. I keep wanting to read “it is, it is, it is.”

Thank you for this stirring remembrance and insight. Fascinating. I will try to apply the lesson of playing the music you don’t hear to my writing: diving for the currents beneath the surface of the story I want to tell.

Another aspect of the lovely Felix Khuner story is mentioned in the introduction to an “oral history” about Khuner from the University of California:

“Felix was often questioned about his memory. I once heard a colleague ask, “Felix, how on earth is it possible to memorize the second violin part of a Haydn Quartet?”

“It’s not possible. Absolutely not. I memorized the whole quartet and played what was missing.”

“Wait a minute! ‘…Played what was missing’?! If you did that everyone else would have played already. You’d be late!”

“Ah no,” Felix said, raising an eyebrow, “Quick reflexes!”

A joke, but not far from the truth. How quick his reflexes could be is shown in this quotation from a 1991 interview with Eugene Lehner, the violist of the Kolisch Quartet, published in Strings magazine. When asked if the

quartet ever suffered memory slips, Lehner said, “There was hardly a performance without one; the question was only how serious. The only one to whom nothing ever happened was Khuner. Once in Paris we had traveled all

night and were rather sleepy we played the Beethoven Op. 95. You know, the second theme of the second movement, the viola begins, and suddenly I realized, “For God’s sake, I have to start this and I don’t know how it goes,

and if I don’t play, there is nobody. And then I hear Khuner playing my part. Afterwards, I said to him, “How on earth did you know I wasn’t going to play?” He said, “You idiot, you were in fourth position on the D string.” I used to play it on the open A. With half an eye, he saw that I was somewhere else on the fingerboard. That quick reaction, it’s just incredible. And you know, the other two were sitting right opposite and didn’t notice anything. If anyone told me such a story, I would say, “Well….”

The fascinating, funny, and biting “oral history” (Vienna, Kolisch Quartet, Schoenberg, etc. – a big ETC!) is available on a variety of sites, including this archived one which shows a variety of download options:

https://archive.org/details/violinistsjourn00khunrich

Best regards from over here,

David Mendes

Leave a Comment

*/