Jules

September 6, 2017

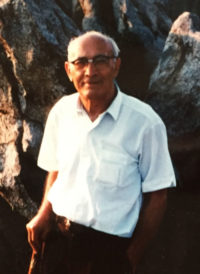

My dear friend Jules Eskin passed away last November at the age of eighty-five.

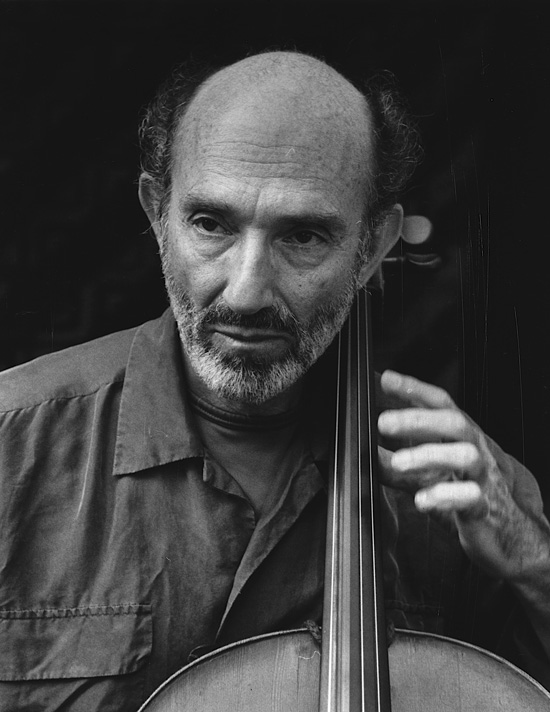

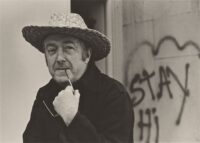

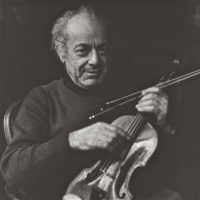

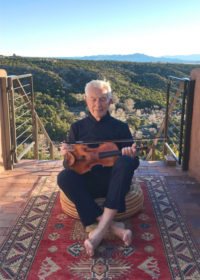

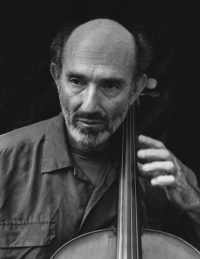

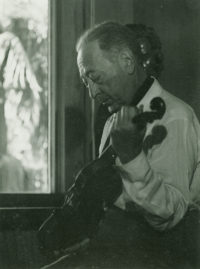

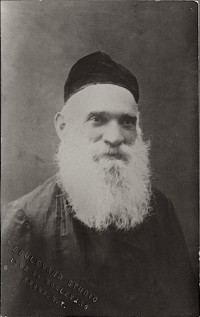

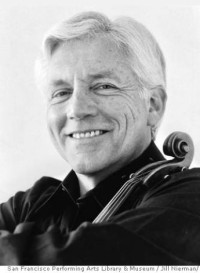

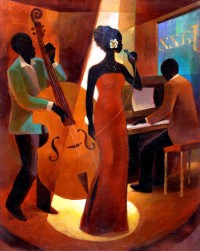

Jules playing his cello, 1994. Photo copyright Dorothea von Haeften.

I first met Jules when he became principal cellist of the Cleveland Orchestra in 1961. I had already been in the orchestra as assistant concertmaster for two years. At twenty-two years old, I was the youngest member of the orchestra, and it was my first job upon graduating from music school. Naturally, I was curious to meet Jules, whose reputation preceded him as a seasoned professional coming directly from New York City. Jules claims, although I don’t remember it, that the first words out of my mouth when we met were: “So, Jules, I hear that you’re a real tough guy.” It was a stupid opening line and in any case, it was not true. Jules could be direct, even blunt, yet he possessed an enormously appealing warmth and liveliness that was irresistible.

And that was the way Jules played the cello. The first time I heard him in an orchestral solo, I swear my heart beat a little faster. Never have I heard a more gorgeous sound coming from the instrument, or such an exquisitely refined and expressive vibrato that always seemed to match the music in question.

Jules and I soon found that we had similar ways of thinking and feeling about music. This became apparent when we compared notes about the various soloists who performed with the orchestra. We’d make bad faces at one another across the orchestra and shake our heads with disapproval if a pianist played woodenly or a violinist played with questionable taste. A very young piano soloist named Daniel Barenboim so impressed both Jules and me that we approached him at intermission and invited him for an evening of sonatas and trios. Barenboim eagerly accepted, and that turned into two evenings of unforgettable music-making, each lasting well into the night.

Jules and I quickly became good friends, but as someone five years older than I, he also acted as an older brother and advisor. He advised me on food (for example, Jules made an outstanding chicken cacciatore); on wine, on shoes, on pipe tobacco (Balkan Sobranie); on sex, romance, insurance policies (not necessarily in that order); and on cars. I did not buy the 1964 Ford Mustang Jules highly recommended, something I’ve always regretted.

At one point, Jules invited me to share the house he was living in. We usually had breakfast together, and here the conversations ranged enormously in subject matter. We talked, of course, about music, musicians, the orchestra, and endlessly about our conductor, George Szell, an object of huge admiration and great fear.

But Jules also took it upon himself to look after me in orchestral matters. Once, when he saw that I was about to leave for a concert despite having a bad cold with fever, Jules barred my way.

“I want you to call the orchestra manager, Trogden, and cancel,” Jules demanded.

“But Jules,” I pleaded, I’m supposed to be concertmaster for these concerts. That’s my job.”

“No, your job is to take care of yourself. Call Trogden right now. I’m getting on the other phone to make sure he doesn’t talk you out of cancelling.”

However, when I called the orchestra manager and told him I would not be able to serve as concertmaster because of illness, he was surprisingly unsympathetic.

“Arnold,” Trogden whined, “what am I going to do for a concertmaster if you don’t show up at the last minute?”

Knowing that Jules was listening in, I suddenly felt much older and more confident. “Trog,” I said, “I understand Sears is having a sale on concertmasters today. Try them.” Jules burst out laughing on the other phone.

At one of those many breakfasts we shared, Jules told me that there would be a Cleveland Orchestra performance of Saint-Saëns’ “Carnival of the Animals” and that he would be performing the movement for solo cello, The Swan. From that moment on, Jules worked on it every day for long periods. I knew The Swan. I had played a violin arrangement of it as a kid. Why all the fuss over such a simple melody, I wondered. But Jules kept at it, and one day he intercepted me as I was leaving the house. “Come into the living room and listen. I have two ways of doing this particular passage. Which do you like more?” he asked. Each way sounded beautiful to me, and I was tempted to tell Jules to stop being fussy and just play the solo from the heart. But there was a difference between the two ways Jules had played the phrase, and as Jules kept on asking me questions, The Swan gradually stopped being a naïve, simple melody, and became a moving story of the stately swan that could be told in an infinite number of ways.

It wasn’t as if I’d never seriously considered the importance of shaping a phrase, a melody, or an entire work of music, but Jules drew me into a world of detail and nuance that I had never imagined before.

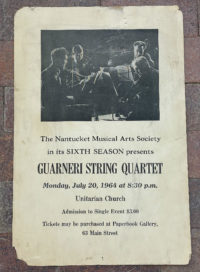

Jules and I both left the Cleveland Orchestra in 1964—Jules to become principal cellist of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and I to form with three of my colleagues a much smaller orchestra, the Guarneri String Quartet. We could not have imagined the long-running and richly rewarding careers ahead of each of us. Jules remained first cellist of the BSO for fifty-three years, and our Quartet performed on the world’s concert stages for forty-five years.

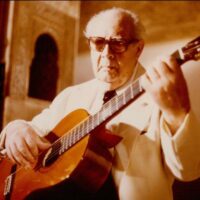

Despite our different lives, Jules and I remained fast friends to the end of his life, and although I enjoyed our summer hikes together and loved to listen to Jules wax poetic about his passion for running, for motorcycles, and for cars, it was music that bound us together. Jules would occasionally sit me down to listen to recordings that he loved. It could be Gregor Piatigorsky playing the Dvorak “Cello Concerto,” Jascha Heifetz doing Irving Berlin’s “White Christmas” with Bing Crosby, or Pablo Casals with the Schumann “Cello Concerto.”

Once, Jules phoned and said, “Put down everything and turn on the radio. Rostropovitch is about to conduct the BSO in Tchaikovsky’s “Pathétique” symphony. I know, I know, he’s not the greatest conductor in the world but it doesn’t matter. You will have an emotional experience listening to his performance as if Tchaikovsky himself were on the podium.”

I did listen, and Jules was right. Never have I heard such a moving performance of the Pathétique. And that was vintage Jules with his contagious enthusiasm, his almost childlike excitement, and his overriding passions.

Not long ago, I brought up the subject of The Swan to Jules—how diligently he had worked on this incandescent melody and also how long and detailed our discussions had been. The experience had made an indelible impression on me, but to my surprise, Jules had no memory of it. Jules thought for a moment and then said, “I don’t remember practicing The Swan, but that melody means a great deal to me. When I listen to cellists auditioning for the BSO, they first play their concerto and their orchestral excerpts, and then I ask them to play The Swan. Once I hear that, I know everything I need to know.”

Jules, once I heard you play The Swan—with that rapturous sound of yours, that most tender vibrato, and with the melody’s contours shaped so compellingly, so lovingly as only you could—I also knew everything I needed to know.

I miss you, Jules, and my heart aches when it comes upon me that you are gone, but on the other hand, I am so deeply grateful to have had you as my friend.

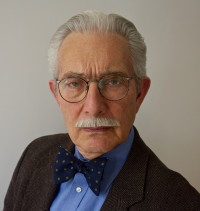

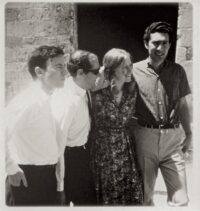

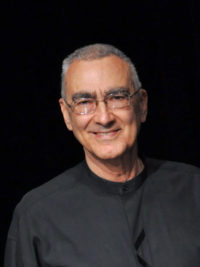

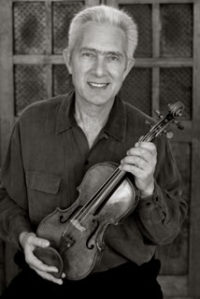

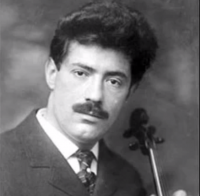

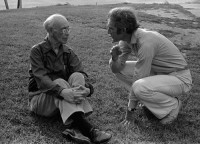

Jules and me on our last hike together, August 2016. Photo copyright Dorothea von Haeften.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

As you know, Marc was a close friend of Jules, too, and he stayed in touch with me after

Marc died, which I appreciated, and I know Marc would have, too. It helped me to feel I hadn’t lost the whole world I’d been connected to through Marc. I have some enjoyable

memories of banter between the two of them. Actually Jules felt that after you and he left

Cleveland, that is when Marc couldn’t take it there any more without the two of you there.

Thank you, Arnold, I look forward to the monthly columns. A laugh or two and a damp eye this morning.

Arnold, What a lovely tribute to cousin Jules. Your comments at his memorial program in Ozawa Hall ere equally touching and heartfelt.

Dear Arnold,

As always your storytelling is superbly written, revealing of his character and your own. Thank you! One tiny correction on the caption for your photo with him. It must have been taken in 2016.

All the best,

Mikell

Thank you for introducing me to Jules – and your friendship. What a loving tribute to a dear friend and to the music that sealed your friendship. I love your retort about the “sale at Sears” – a good reminder to take care of ourselves……..

Thank you,Arnold!

I am crying again and again…..

Yes,last photo of two of you was taken in August 2016

It is almost a Year since he left us…

Dear Arnold! Thanks for your beautiful and heartfelt tribute to Julie Eskin! Dorothea’s photo perfectly captures your abiding friendship! Brought a tear to my eye.

Friends are forever, especially when they had touch you with their music! Thank you for made me see my music friends as something that I will have to keep in touch no matter what… life is to fragile… love and music.

Dear Mr. Steinhardt, I always appreciate your heartfelt observations about the intersection of life and music.

Tim Lorsch

Mr. S.,

Thank you for this lovely story. I also loved Mr. Eskin’s artistry. You have added so much to my own appreciation of him. Thank you.

I forwarded this story to 2 Cellists who knew Jules Eskin–David Geber & Alan Stepansky.

They thank you and say “Arnold writes as beautifully as he plays”.

This was very touching. Music has a way of keeping people together even when they are gone. I never met Jules but I now feel connected to him through your writing.

Thank you for your beautiful story Arnold; I do enjoy your musings and heart-felt stories like this one. Very best from Australia (well from me! AND Australia!!)

I was scrolling down (up?) your list of short stories, stopping at the one on Jules Eskin, as memories came rushing in.

I met him at the same time I met you. It was at Jaime & Ruthi Laredo’s New Year party.

Jaime has just won a competition (the Belgian Queen’s one?) Michael Tree was there too, and Jules, and many others.

I was 5 months pregnant. You and I were sitting at the curve of the piano, talking.

I remember our conversation as if it was yesterday.

It is difficult to actuate a time passing.

Hava

Leave a Comment

*/