Tempo, Friend or Foe

June 10, 2021

What are the most basic things that must be accomplished in order to master a work of music?

I think even contentious Democrats and Republicans can agree that the first order of business regarding everything from Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony to “Tea for Two” is, plain and simple, just learn the notes.

Next come the rhythms attached to those notes. In this case, executing the rhythms correctly also seems perfectly reasonable advice, but music played strictly and in unyielding fashion according to the metronome has its dangers. A listener might suspect that this kind of music making is the robotic product of an artificial intelligence lab rather than that of a live, breathing human. And so, yes, learn the rhythms, but here we musicians have a certain amount of wiggle room. There is an ebb and flow to rhythm: this note a little longer, that one a little shorter, rushing here or holding back there, in effect defying the stiff and uncompromising school marm metronome. Curiously enough, this kind of tinkering gives musicians the chance to capture a rhythm’s true essence in the process.

So, what’s next? Ah yes, tempo. All music has to have a tempo, but here we have far more than wiggle room. The composer’s lingua franca for tempo instruction is Italian—for example, Adagio for slow, Andante for a walking tempo, Vivace for lively, and Presto for fast. But how slow should Adagio be, how quick Andante, how lively Vivace, or how fast Presto? I hope you and I will not come to blows if we disagree on a walking tempo, but if you have longer legs than I, disagree we often will. Tempo is in the ear of the beholder.

And so, the invention of the musical chronometer by Dietrich Nikolaus Winkel in 1814 promised to be such a useful tool in deciding tempos that Johann Nepomuk Maelzel stole Winkel’s idea, called it a metronome, and began manufacturing it in 1816 as “Maelzel’s metronome.”

In November 1817, Ludwig van Beethoven wrote a letter to Ignaz Franz Moser in which he stated, “As far as I am concerned, I have been thinking for a long time to give up these absurd terms Allegro, Andante, Adagio, Presto, and Maelzel’s metronome gives us the best opportunity to do so. I give you my word here that I will use them no more in all my newer compositions”.

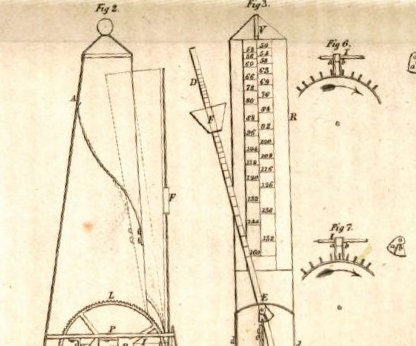

A diagram from Maelzel’s patent for the metronome.

Since its invention the metronome has been taken seriously by many composers, and performers as well. But not by all. I’ve often heard their doubts: “How can you trust Beethoven’s metronome markings? He was deaf when he decided on them”, or “Metronomes were too inaccurate in those early days to be taken seriously”, or “Schumann’s metronome markings are so quirky”, or “Composers often ignore their tempo markings when recording their own works. So why shouldn’t I?”

Still, as time goes on, there has been an increasing interest in a composer’s metronome marks. In 1942, Rudolf Kolisch, of Kolisch String Quartet renown, gave a lecture in New York City entitled “Tempo and Character in Beethoven’s Music.” In installments, Beethoven provided metronome marks for all nine symphonies, the Missa Solemnis, his Septet, and the first eleven of his string quartets. Kolisch countered a prevailing view that Beethoven’s metronome marks suffocated artistic freedom. He maintained that the composer was dead serious about their importance in probing the essence of his music. Indeed, Kolisch was the first to conduct Beethoven symphonies according to their metronome indications. Not everyone was pleased with Kolisch’s premise. The legendary conductor Otto Klemperer, who attended the New York lecture, was said at its end to have raised his hand and asked, ”Kolisch, can you tell me where the men’s room is?

When all is said and done, tempo can be your friend or your enemy. A tempo that’s too fast or too slow impairs all the other musical considerations, but when you’ve found a basic tempo that truly meets the music’s needs, things seem to fit into place so much more easily. Of course, your right tempo might not be mine, and my right tempo today may not be the same tomorrow.

Musicians have time to ponder a work’s tempo during personal practice, in rehearsal, and in that moment of glorious truth, performance. Of special interest, however, is when a work can be performed multiple times. It presents the opportunity for a basic tempo to be examined over and over again.

That was certainly the case with our Guarneri String Quartet, on tour with the same music night after night. Naturally, there were instinctive tempo adjustments depending on a hall’s acoustics. If they were overly reverberant in Des Moines, we might have wanted to slow the tempo down a tad for clarity’s sake, or speed it up if the hall was bone dry in Oshkosh. In addition, with each performance, not only basic tempo came under examination, but also the need for fluctuations within it. Was this section too static, that one too rushed? And who knows whether something as insignificant as getting out of bed on the wrong side on a particular morning might have affected our mood and, therefore, the tempos of our performance that evening. (Note: the Guarneri String Quartet did not sleep in one bed on tour).

Beethoven’s String Quartet Opus 59, No. 3 was one of the works to which he assigned metronome marks, and the last movement’s Fugue, Allegro Molto, caused quite a stir in string quartet circles. His wildly fast 84 to the bar was at the very edge of technical possibility. Were the deaf man and his undependable metronome at fault, or did Ludwig really want quartets to break the sound barrier as they stormed through the movement?

On our first recording of all the Beethoven String Quartets for RCA, we more or less reached the hair-raising metronome speed of that last movement. The tempo seemed at that particular moment in our lives to help capture the sparkle, the brilliance, and the sheer joy of the movement. Many years later, we once again recorded all the Beethoven quartets for Philips records, but this time the Fugue came out somewhat slower. Had our tempo friendship ripened into something more reflective, or had we simply become old codgers no longer capable of razzle-dazzle speeds?

I cannot recall many of the innumerable times that tempos were discussed and often altered in our quartet’s eternal quest for true tempo friendship. But a particular event is indelibly etched in my mind. On one of the Guarneri’s yearly European tours, we often ended concerts with Opus 59, No. 3. During intermission of a performance in Eindhoven, Holland, Michael Tree, our violist, came to each of our dressing rooms with a request. “I think we played the Fugue so fast in Amsterdam last night that the music’s details became blurred rather than brilliant. Do I have your permission to start the Fugue just a touch slower?” he asked. Of course, violinist John Dalley, cellist David Soyer, and I all agreed to Michael’s request. Perhaps we had gotten carried away with the tempo. In any case, the viola begins the Fugue alone, so it would be up to Michael to decide its tempo.

I more or less forgot about our back stage conversation as we performed the quartet for the Dutch audience. Only in the short introduction to the last movement did it occur to me that, ah yes, Michael plans to play the Fugue slightly slower. But Michael did not play the Fugue slightly slower. What came out of his viola was the slowest tempo I’d ever heard—really a practice tempo. John, David, and I looked at each other in disbelief, for it was obvious that Michael had grossly miscalculated. One by one, the rest of us dutifully made our fugal entrances, but if you’re used to a breathtakingly fast bullet train, how does one deal with a pokey, sleepy milk train? For better, but probably for worse, we got through the movement at this somnolent tempo, bowed more hurriedly than usual, and rushed to the wings so that we could accost Michael. “I know, I know, it was too slow,” Michael, red faced with embarrassment, shouted above the din of the audience still clapping. David, who looked rather sternly at Michael, had an immediate response, “We are going out there right now to play the same movement as an encore, and you, Michael, are going to play a proper tempo.”

Michael did not play a proper tempo. Possibly somewhat rattled by his earlier misstep, and perhaps a victim of adrenalin rush, Michael launched into a tempo that must have broken all speed records. Once again, John, Michael, and I looked at each other in disbelief, and hoped we could hang on to the bullet train ride he had created.

I have no idea what the Eindhoven audience must have thought of our performance, but the Guarneri String Quartet continued on its European tour the next day with the knowledge that the night before we had seen the enemy—actually two of them, one too slow, one too fast.

Our Guarneri Quartet performed Opus 59, No. 3 dozens of times both before and after the Eindhoven concert. As far as I can recall, Michael always set a truly exciting but always playable tempo for the Fugue. He and the Fugue obviously were fast friends. And the proof was in the pudding. As Beethoven’s miracle of a Fugue rushed to its end, Michael’s choice of tempo would often bring audiences to their feet.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

Interesting essay. I have strong notions about tempo, and when I hear a performance that departs far from what I am used to, I have a visceral reaction of great annoyance. And when playing in groups and the tempo is too slow, I try to incrementally speed everyone up — or the reverse, if it’s too fast. Sometimes this works. Doesn’t that sound self-centered?

I remember a time at a Vermont Mozart Festival concert in Burlington years ago, when the conductor set a blistering pace that the soloist couldn’t keep up with. Don’t recall the piece or the soloist, but the soloist was one angry man, who turned beet read when he bogged down, and stormed out of the hall as soon as the piece ended. I can only imagine the accusations that followed.

I love this story, thanks again for your tales. You don’t mention the Czerny tempo markings supposed recalled from his work with the master. That’s the amazing thing about live performances, the excitement of the moment. I think as a singer I didn’t use metronome markings, but usually worked with a coach who had his/her own opinion. So it goes.

oh thank you for providing joy and whimsy and taking my mind off unimportant stuff. I’m just so lucky my son introduced me to your work, and I get to be entertained and have my mind changed. Only, good.

Elegantly negotiated, in the moment and in the writing.

Love all your stories…and this might be the best yet. Your discussion of Tempo, that touchy subject, is filled with valuable information, interesting examples and laugh-out-loud humor. Thank you!

If you want quick tempi, listen to the Aram Quartet! Great story and v interesting about the metronome, it hasn’t changed!

Hello Arnold. I have enjoyed your storytelling tho not a musician myself. We met long ago on the island of St. Croix when you were vacationing at Wally Scheuer’s house. I enjoyed our conversations and have thought of you often. I hope all is well.

Leave a Comment

*/