Ach, you made a mess of it

May 5, 2021

Have you ever regretted something you’ve done or said? I certainly have. Out of the clear blue, an unpleasant or embarrassing or foolish moment from the past will pop into my brain. How could I have done or said that, I’d think, shaking my head sorrowfully. Since whatever had happened, unfortunately, couldn’t ever be erased or taken back, I’d often try to rationalize my behavior: I was young, or, my emotions got the better of me, or, I’m not perfect, just like every other human being.

An uncomfortable thought: Perhaps axe murderers say the same thing as they’re led to the gallows.

In any case, more often than not, the thoughts would slip out of mind just as easily as they slipped in, and I would proceed with my life.

To a certain extent, the same might be said of my role as a performing musician. Do I always perform spectacularly? Of course not. Do I have regrets about certain concerts that did not go as well as planned? Sure. But how well did I really play? Most often, music is performed and then, poof, it’s gone into thin air. What remains is only the shaky memory of both performer and listener as to what actually transpired.

But does performed music always go poof?

Not if it’s recorded. Those performances may come back over and over again to either give you joy (wow, that went really well), or, just as easily, haunt you (how could I have played like such an idiot!).

I encountered the recording beast early on. At age ten or eleven, my violin teacher thought I’d improved enough for him to assign me a somewhat advanced student piece in the Hungarian style called Son of the Puszta. Dad was so proud of my progress that he phoned our up-to-date relatives, Irving and Bela Taft, and arranged for me to play Son of the Puszta on their newfangled recording machine. Irving placed an acetate disc on the spinning turntable, carefully lowered the arm’s needle onto the disc, and then signaled for me to begin.

Son of the Puszta did not go well. Perhaps it was the newness of the recording experience, or the expectations of dad for his oh-so-talented son, but I became nervous and played poorly. As Son of the Puszta came to its end, dad voiced his disappointment in my performance succinctly: “Ach, you made a mess of it,” he exclaimed. Unfortunately, Irving had not yet lifted the arm off the revolving disc, and so my dad’s disapproval, as well as my poor performance, was recorded for posterity.

Did this event cause psychic scars? Not really. Dad was my biggest fan, but an honest one. Sometimes he lavished praise on me for a performance, other times, well, not. As a matter of fact, I’ve kept the now unplayable disc all these years as a kind of talisman.

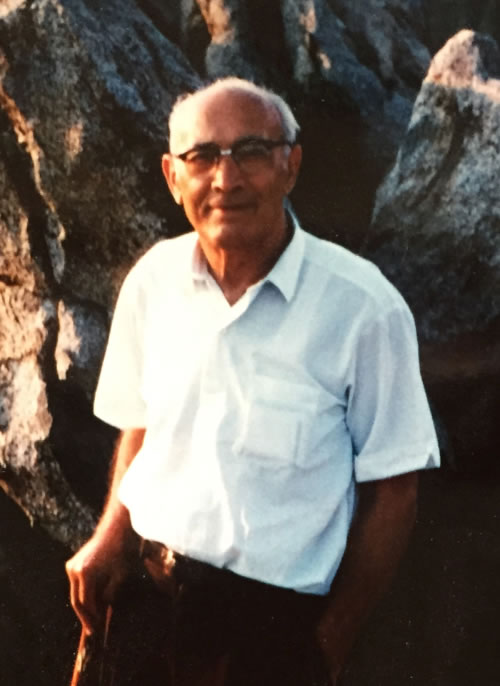

My dad, Mischa Steinhardt.

After the Son of the Puszta debacle, my young performances were recorded with some regularity. Dad no longer needed to be a critic, for I had taken on the role: Wieniawsky Concerto #2 with piano, age twelve (quite impressive for a kid my age), Lalo’s Symphonie Espagnol with the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, age fourteen (a bit shaky), last movement of the Tchaikovsky concerto with orchestra, age seventeen (pretty good but lacking detail).

Recordings continued to be a part of my performing life—first as a student, then as a soloist and recitalist, and finally as a member of the Guarneri String Quartet. For the most part, I’ve taken a philosophical attitude towards those recorded performances. Whether they went well, or badly, or even something vaguely in the middle, I could always take comfort in having tried my best.

There was, however, one exception that stands out in my mind.

In 1958 I won the Leventritt International Violin Competition. The prize was solo appearances with six major symphony orchestras. Five of those went well enough, but the sixth, with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, made me uneasy whenever it came to mind as the years passed. I couldn’t recall much about that performance of the Mendelssohn violin concerto, but I remember that two famous violinists were in the audience and that they both came back stage to greet me afterwards.

One was the comedian Jack Benny, who made a career out of playing the violin badly. Moments before my only rehearsal with the orchestra, Benny had barged into my dressing room and with mock anger accused me of making him look bad. He had planned to play the very same Mendelssohn concerto in a benefit concert for the orchestra’s pension fund, but refused to be out-fiddled in the concerto by an upstart young kid—me—so he changed works.

The other violinist was Isaac Stern, one of the great soloists of his generation. I had played for Stern as a student, listened to him countless times in concert, and would later in my life perform chamber music with him.

Something about the combination of my Mendelssohn performance and Stern’s presence made me uncomfortable just thinking about it. I couldn’t explain it to myself, but I resolved never to listen to that particular performance—that is, if it had been recorded at all. Let sleeping dogs lie.

Alas, it had been recorded. My friend and colleague, violinist Ken Goldsmith, who had joined the Detroit Symphony Orchestra the year I performed with them, offered to send it to me. Then, acquaintances of mine in the recording industry began offering it to me as well. Thanks, but no thanks, I told them all.

But those sleeping dogs had apparently awakened for the ages. Recently, a friend sent me a link on YouTube to the entire concert performed on November 9, 1958, by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, Paul Paray, conductor.

I stared at the link, uncertain what to do, and for the first time in a long time, I began talking to myself.

Arnold #1: So, Arnie, old boy, what’s up?

Arnold #2: I’m nervous.

#1: I can see that, but why?

#2: I’m nervous about a performance of mine I don’t want to hear because I might not like it.

#1: Wait a minute. Are you talking about your performance of the Mendelssohn concerto sixty-one years ago?

#2: Uh, yes.

#1: I don’t believe this. Who cares how you played five million years ago?

#2: Well, I do.

#1: Hmmm. I suspect this is a symptom of the dreaded Son of the Puszta complex, and the fear of dad’s “Ach, you made a mess of it.”

#2: Tell me, do you have a license to practice psychotherapy?

#1: Don’t be a wise-ass and just press the link.

#2: Just press the link?

#1: Yes, just press the link so we can hear the Mendelssohn concerto.

They listen to the first movement.

#1: Well, what’d you think?

#2: Not so bad.

#1: Not so bad? Give me a break. The opening was sweet, the octaves at the end of the opening statement pretty much in tune, and the second theme quite expansive.

#2: It could have been much worse.

#1: OK, Mr. Noble Perfectionist, let’s go to the cadenza. Pretty good, huh?

#2: I have to admit, pretty good.

#1: See, nothing to worry about in the first movement. Round one, a winner.

#2: This is not a boxing match, Steinhardt versus Mendelssohn.

#1: Objection noted.

They listen to the second movement.

#2: You know, I rather liked my playing, A couple of old fashioned things I wouldn’t do any more, but still, nicely done, even the closing cadences.

#1: Now you’re talking, Arnie, baby. I’m beginning to like your attitude.

They listen to the third movement.

#1: Well?

#2: I played like a vilde chaya.

#1: Stop with the Yiddish words.

#2: OK. I played like a wild animal. Way too fast. So little charm. And to think that Isaac Stern was there.

#1: Aha. Now we’re getting to the source of your tzures.

#2: Look who’s throwing around Yiddish words.

#1: “Trouble,” if translation is needed. I know what this trouble is all about.

#2: And now, so do I. It was remembering Stern’s stunning performance of the Mendelssohn with the Philadelphia Orchestra when I was a student at the Curtis Institute of Music. Great fiddling, but always in the service of incomparable music-making. What style, what elegance, what sweetness of tone! And the last movement! No show-off moment for Stern there, but rather a sense of dance, a joyous outburst of good cheer, and a feeling of unalloyed optimism.

#1: And poor Arnie just rushed through that last moment like a vilde chaya.

#2: Yup.

#1: Listen, sweetie. Stern was once twenty-two years old just like you were when you performed the Mendelssohn. You know what guys are like at that age: fast cars, fast food, and fast third movements of the Mendelssohn violin concerto. So you played it like a young virtuoso instead of a wise man—congrats.

#2: You can talk till you’re blue in the face, but I should have known better than to rush through this glorious movement. Why, the orchestra barely kept up with me and. . . .

#1: Stop right there. I’ve just had a brilliant idea. I’m going to perform an intervention on you.

#2: A what?

#1: You heard me. An intervention.

#2: Will it hurt?

#1: Possibly. Now close your eyes and imagine that you’re back at Bela and Irving Taft’s house. You’re standing in front of their newfangled recording machine, except instead of recording Son of the Puszta, it will be the Mendelssohn concerto with the Detroit Symphony Orchestra.

#2: You could never fit the entire orchestra in the Tafts’ living room.

#1: In your mind you can. Trust me.

#2: OK. They’re there. Now what?

#1: Irving lowers the arm’s needle onto the revolving disc and you perform the Mendelssohn just like you did. And afterwards, as Irving is about to lift the arm off the disc, what is dad’s opinion of your performance?

#2: You know, honestly, I think he’d like it. I played well enough, rather musically, and there were at least a few special moments.

#1: I think so, too. And the third movement?

#2: Dad cherished music that was moving enough to bring him to tears, but he also loved the virtuoso fiddler. I suspect he would have enjoyed my vilde chaya take on the third movement.

#1: And with that, let’s bring the intervention to an end, Arnie, old pal.

#2: I don’t know why, but I feel much better about my performance of the Mendelssohn violin concerto.

#1: I knew you would.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

Fabulous performance! Yes, the 3rd movement was a very fast ride, but you still controlled that wild stallion. Wonderful to hear your trademark sweetness of tone, too. I hope you and Dorothea are well and vaccinated.

Beautiful!

In 1958 my late husband, oboist Marc Lifschey, made what among musicians is considered an iconic recording of Bach cantata #82 with Robert Shaw conducting and Mack Harrell singing. He was unhappy with the recording and did not own a copy of it. Soon after we were married a friend invited us over and when we arrived, we heard that work coming from the stereo. Marc said, not having any idea who was playing, “That’s pretty good oboe playing” and our friend said, “That’s you!” Marc said to me a few minutes later, “Now I hear the most ghastly flaws!”

Love this story! I listened to the DSO recording, and it is delightful. I also enjoyed the interview with a very young Arnold after the piece.

Nice playing, kid! Keep practicing and you might make a big name for yourself (and three other string players). (Now, it was the trumpet player in the opening of the Mahler who sounded nervous, not you).

Son of the Puszta (not Puzsta!). Prairie in Hungarian is puszta. Great essay otherwise!

Dear Arnold,

Thank you very much for your most recent Strawberry. I was born and lived in Detroit and had a subscription to the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. While I may have been in your audience then, I certainly have enjoyed decades of attending your Marlboro Music concerts. This Friday, Chris Serkin will advise us trustees of the 2021 festival plans.

Best regards,

Harvey Traison

I liked the tempo of the third mvmt. Just what I am used to hearing. Certainly no rushing. A fine performance.

Dear Arnold, what a joy! Especially for a psychoanalyst. The memoir portion is precious and I love the story about your father and the photo, but the back and forth between your Super ego and your superior ego (if you want a definition or a sense of the difference between the two, one is a healthy self-consciousness and the other is a very destructive, critical and infantile aspect of the psyche. And that fabulous outcome, resultant with the gift of the YouTube recording of not only your performance but the introduction. Thank you again so very very much; it means even more to me now that my memoir is coming out, for sure for sure, June 1! And it has provoked me to create a small website and even my own brief and somewhat whimsical blog complete with photos. Perhaps you’ve already had a chance to take a peek at it. Hope it’s entertaining. But no chance it can possibly be as wonderful as your blog, a continuation of those two fabulous memoirs of yours.

With warm regards, Judith

You once wrote in your book, “What does the music have to say and how will we say it?” When I hear this sweetly melancholy piece, I, like Mendelssohn, “am lying under apple trees and big oaks.” You played it sublimely. Mrs. Zigmond was right not to sell her house.

Leave a Comment

*/