But the Melody Lingers On

December 1, 2013

About to walk across New York City’s Central Park on a sunny winter day, I suddenly heard the strains of Santa Claus is Coming to Town wafting out of a nearby workman’s truck radio. What a silly melody, I thought to myself absentmindedly. Twenty minutes later, I had crossed the park but to my consternation, Santa Claus was still coming to town. The song simply refused to stop spinning around in my inner ear, something the Germans refer to as an ear-worm.

But let’s give the Santa Claus song its due. The melody has staying power—not only in my brain as I traversed Central Park but also when it’s played Christmas after Christmas. First sung on Eddie Cantor’s radio show in1934, the song became an instant hit with orders for 100,000 copies of sheet music the next day and more than 400,000 copies sold by that Christmas. People must have liked not only its catchy words but also the melody itself.

What mysterious combination of notes, rhythms, and harmonies makes a melody successful? To steal from a memorable Supreme Court opinion on pornography, I can’t define a great melody, but I know one when I hear one. Gershwin’s Summer Time is a perfect melody. So is Beethoven’s Ode to Joy. A great melody can be long and complex as in the opening of Mozart’s G Major Piano Trio, K496, or short and almost childlike in its simplicity as in the end of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, first movement. What all these melodies seem to have in common is a certain rightness or inevitability about them.

We go about our lives with easily hundreds of melodies stored in our brains. Are they in some way categorized up there between the ears? Mary Had a Little Lamb under KIDS, Some Enchanted Evening under SHOW TUNES, Ravel’s Bolero under CLASSICAL. Or are the strands of synoptic memory laid out willy-nilly so that Pop Goes the Weasel might snuggle up with the Cavatina from Beethoven’s late String Quartet in B Flat? Some melodies can be summoned almost without thinking. I’ll absent-mindedly hum a Beatles tune while driving or casually whistle a song from West Side Story as I stroll down the avenue. Other melodies succeed in being coaxed out into the open only with a little help. Could I sing the great trumpet solo of Shostakovich’s First Symphony stone cold? Maybe not, but if I heard the first few notes on the radio, it would be quite easy for me to sing along with the rest. There must be some biological need for us to house this library of melodies but I suspect only those with character, balance of form, and distinctive profile get library cards. I sometimes think of a great tune not as a series of beautifully assembled notes but as an ironclad structure made up of only absolutely essential interconnected parts—take away even one of them and the whole thing collapses.

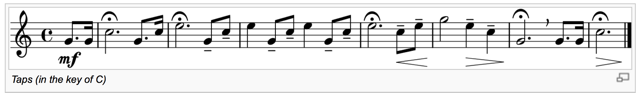

Taps, sounded at dusk, and at funerals, particularly by the U.S. military, is that kind of melody. The tune is in fact a variation of an earlier bugle call known as the Scott Tattoo, which was used in the U.S. from 1835 until 1860 and was arranged in its present form by the Union Army Brigadier General Daniel Butterfield, an American Civil War general. The melody is composed entirely from the written notes of the C major triad (i.e., C, E, and G, with the G used in the lower and higher octaves). This is because the bugle, for which it is written, can play only the notes in the harmonic series of the fundamental tone of the instrument.

Think of it! A melody made up of only three different notes—well, four if you count both the upper and lower octaves of G. Even visually, it looks so simple. Three steps up—the longer one in the middle—followed by three small steps down, and a final answering step up. Taps is an entire world of emotion, beauty, and perfect form encapsulated in one short, streamlined statement.

If defining a successful melody proves too elusive, perhaps longevity is a useful yardstick. Most melodies come and go but the good ones, those with that ironclad structure made up of only absolutely essential interconnected parts, might be played, sung, hummed, or whistled for decades, even centuries. Which will actually last for the ages? I think Taps will. Beethoven’s Ode to Joy will. Unfortunately, so will Santa Claus is Coming to Town.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

Talk about your ear worms! The never-ending melody that constitutes the first theme (cyclical form and 27 bars long – count ’em) of the Cesar Franck sonata may just be the ear worm from hell. From the seemingly innocent entry of the piano part, you know you’re in for it. Just try and shut the damned thing off till the very last bar. Yeah, just try.

Wonderful story. I would have to say that my “ear-worm” is definitely Ravel’s Bolero.

Leave a Comment

*/