A Meditation on the Meditation

March 1, 2011

In the ancient Egyptian city of Alexandria, the courtesan, Thaïs, reflects on her past life of worldly pleasure. Looking into the mirror, she worries that her beauty will soon fade. The monk, Athanaël, arrives at her palace, admonishing Thaïs that there is one kind of love she does not yet know. He exhorts her to prepare her soul for eternal life, in order to rise resurrected from the grave of sin. At first, Thaïs mocks him, but gradually her feelings turn to apprehension. Trembling, she commands the monk to reveal this mysterious love. Athanaël, who has secretly struggled with visions of the ravishingly beautiful Thaïs, violently calls on her to repent. She is terrified. At that moment, Thaïs hears her lover’s voice outside, pleading for her affections. She scorns him and, casting her eyes wildly about, vilifies all those who are wealthy and happy. The monk leaves, announcing resolutely that he will wait before her palace till daybreak for her answer.

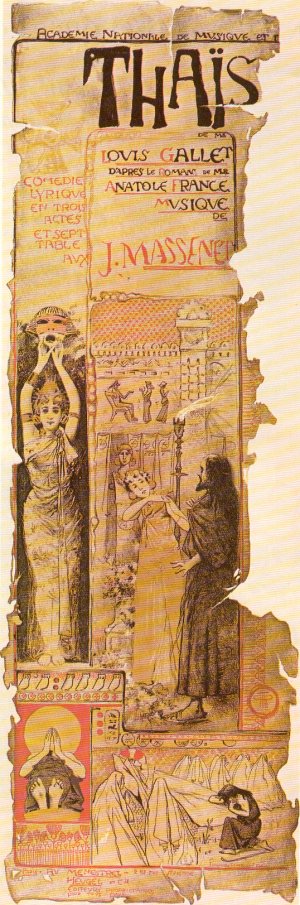

This is not a slice out of fourth century Egyptian life, but the theatrical centerpiece of a French opera, Jules Massenet’s Thaïs, which made its debut on March 16, 1894, at the Paris Opéra. Sitting mutely on stage during the second act, the aging courtesan struggles for her soul—her meditation enacted by characters moving silently behind a scrim. The audience awaits the traditional aria that will bring Thaïs’s meditation to life, but Massenet does something daring. He removes all music from the stage, handing it entirely over to the orchestra. Released from verbal and aural constraint, Thaïs roams in each listener’s heart and mind with a more private relevance.

A sensual, semi-religious incense wafts alluringly out of the orchestra pit in the form of a florid melody redolent with sweet and poignant memory, tenderness, sorrow, regret, turbulence, drama, anger, resignation, and finally, acceptance. Strings and harp provide a gentle accompaniment, but the powerful aura filling the opera house is created in large part by a single instrument: the violin. Massenet could have chosen any orchestral instrument to describe this singular moment but the violin, so like the human voice in its ability to sustain and to sing, takes on the qualities of the courtesan herself. The concertmaster’s bow gliding across the violin’s strings is not so different from the column of air that rushes past the vocal chords, but truth be told, the violin can do so many things better than Thaïs. For one, the violin encompasses not only the alto and soprano vocal range, but also out-distances both registers as the Meditation soars far into the stratosphere. The concertmaster’s hands are almost like two different actors in one body. The fingers of his left hand shift along the strings with an adroitness and brilliance that Thaïs would envy, yet he can modulate the vibrato in an infinite variety of speeds and shadings the way the courtesan’s vocal stand-in might. The other actor, the right hand, expresses with the bow her longing, her sighs, her gestures as if it were a feather or paint brush; or her anger, displeasure, and heartache by applying it with unrelenting pressure, bursts of speed, or knife-like thrusts.

Massenet’s opera ends badly. Thaïs, dying in the monastery after three months of penance, again meets the monk, Athanaël, who has been haunted by her profane and voluptuous beauty. He confesses that it is she who has converted him to worldly love. As Thaïs falls dead, the monk collapses in despair.

Thaïs’s Meditation, is a perfumed and poignant turn-of-the-century melodrama, but it seduces others beside Athanaël. It took only a generation after the opera’s debut for the Meditation to become a rite of passage for fiddlers. This aria without words poses no insurmountable technical difficulty, but the beauty of its long, winding melody buttressed by languid harmonies is elusive and challenging. In the course of the Meditation’s four or five minute length, a violinist is called upon to provide a coherent form, subtleties of detail, intensity of feeling, and an organic transition through a variety of powerful moods.

The number of violinists who have tried their luck with the Meditation since its debut is anybody’s guess. As early as the1920’s, six different recordings were listed in Alberto Bachmann’s Encyclopedia of the Violin. Two of them, made by Mischa Elman and Fritz Kreisler, came into my possession in the1950’s as people began abandoning their bulky old 78 R.P.M. records for the new, lighter long-playing ones. At mid-century, there was no living violinist who did not revere Kreisler and Elman. When you listened to Kreisler, the nineteenth century seemed to reappear, unfolding gently before your ears. Kreisler’s playing had a warmth, leisureliness, and freedom that brought forth the vanishing attributes of an earlier era. People loved his playing but, moreover, they left the concert hall more content with themselves and thinking that the world wasn’t half-bad after all. Indeed, when Kreisler appeared on stage, his mustached, smiling, and avuncular presence itself is said to have evoked minutes of applause before he even lifted violin to chin. As for Elman, my parents had taken me as a child to hear him perform. What I remembered most was the incongruity of how this short, balding, and homely figure who weaved awkwardly back and forth could sing on the violin, how lustrous was his tone, and how he seemed to revel in it.

Despite Kreisler and Elman’s reknown, the records did not interest me particularly. The Meditation had suffered the fate of many pieces that are too successful for too long. For those composers with the good fortune to write something well crafted enough to capture the public’s imagination, danger lurks in the wings. The work is first discovered, then performed, and finally adulated. So far, so good. But from here on, it runs the risk of being overplayed, worn thin, ridiculed, and finally reviled. After fifty years of flight, Massenet’s song on wings began to wobble and became the butt of jokes. At the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, we used to call it the ‘Medication’ from Thaïs. I was more drawn to the new music of Bartok, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, and Prokofiev, composers in the musical laboratory of the twentieth century. For me, the Meditation had become a curiosity, a relic from another age.

Kreisler and Elman’s artistry, however, meant a great deal to me. I wondered why two famous violinists had recorded the same piece at more or less the same time. What was all the fuss about? I pulled the solid feeling yet very breakable 78 R.P.M. records gingerly from their perch and looked them over. Both, made by the Victor Talking Machine Company, featured a logo of a dog looking perplexed as he peered into the horn of a wind-up record player. “His Master’s Voice” was inscribed underneath, and in larger letters “Thais—Meditation” with the artist’s names at the very bottom. So it wasn’t the ‘Medication’ after all; but a meditation… about what, though?

I pulled the Kreisler out of its stiff paper sleeve first and placed it on the record player’s turntable. Only years later did I learn that Kreisler had recorded two versions of the Meditation accompanied by Carl Lamson at the piano on February 2,1928 (his birthday). Such was the popularity of both the artist and the work that both takes were released.

The old record emitted a frightful collection of crackles, pops, and hisses that yielded only reluctantly to the pianist’s gently ascending introductory chords. Then Kreisler made his entrance. Nothing was ever forced about his playing. Kreisler’s tone was robust but with an underlying resonance that made me think of a deep, lusterous lacquer applied in many coats. The shaping of the music was radiant and supported by a narrow, pulsating vibrato. When the record came to an end, there was little to say. Fritz Kreisler had bridged the passing styles of time and survived the surface noise of this old disc to deliver a performance of intoxicating beauty. A great poet had spoken. To my surprise, the Meditation itself had also affected me. There was a devotional yet sultry magic in the way the melody stepped down and rose over and over again.

Kreisler’s interpretation had been so all-encompassing that the Mischa Elman version seemed irrelevant, but I placed the other disc on the turntable. Again the scratchy surface, again the two bar piano introduction, this time played by Percy B. Kahn. Elman’s violin sang with an aching sadness. The tempo was faster than Kreisler’s, allowing the solo line more freedom and impulsiveness. But Elman seemed to seek out a very specific quality of tone. He was like a miner excavating the strings of his violin for veins of sound rather than gold. His tone’s sheer opulence bathed the senses seductively. Where Kreisler had been noble, Elman was touching, but of the two versions I could not say which affected me more.

As time has elapsed, most violinists and their audiences do not even know or have long forgotten what the Meditation’s original intent was. At a wedding of two violinist friends of mine, the groom, Andy Simionescu, in formal attire, played the Meditation for his bride, Pamela Frank, at the altar. Bedecked in a cream-white wedding gown complete with veil and train, Pamela was clearly transported by Andy’s declaration of love. Later, it occurred to me that the young man might have reconsidered his choice of music had he only known that Thaïs’s plans did not include marriage. At that very moment in the Opera, she was considering whether to repair to the convent or remain a high-class call girl.

I met Elman at a violin shop the year before he died in 1967. The rare instrument dealer, Jacques Francais, introduced me as the first violinist of the Guarneri String Quartet. This was all Elman needed to perform an hour’s worth of first violin parts from the great string quartet literature for his captive audience. A wave of recognition swept over me. It was that same sound I had heard on my old record and frankly, it gave me a lump in my throat. How did he do it, and where did it come from? Was it the pressure of the bow? The way his fingers touched the strings? His vibrato? As Elman played for me with a backdrop of dozen’s of string instruments either hanging in glass cases or scattered willy-nilly around the shop, I searched for a clue to his magic, but found none. He looked like any other violinist. I had to conclude that Mischa Elman’s sound, not to mention his musical conception, came from somewhere else, perhaps the place where heart and mind secretively meet. As for telling him how much I loved his recording of the Meditation, in the excitement of the moment all such thoughts vanished in the violin shop air heavy with the smell of varnish, glue, and rosin.

These days, when I occasionally listen to Elman’s Meditation, I feel almost like an intruder, even a grave robber. Elman died many years ago and yet, his Meditation is so alive, so touching. How is it that a human being whose physical traces have vanished from the earth can still bring tears to my eyes? Why make Mischa Elman play the Meditation over and over, I ask myself. Let the dead rest in peace. And yet, without this disembodied representation of him, my life would be poorer for it.

The Meditation, a mere drop in the immense ocean of the violin repertoire, is one of several works I singled out not to play for many years. Call it youthful close-mindedness. But in middle age, the alluring courtesan’s implicit invitation became irresistible. I worked through the Meditation with the confidence of an experienced musician, but quickly became mired in details, all small in themselves but each a crucial part of the overall design. What speed should my vibrato be, and when and how should I vary it? How should I shape the phrases? When should I let the tempo move forward and on which notes should I linger? These were, in fact, some of the same things I wondered about in the violin shop those many years ago as I searched for a key to Elman’s artistry.

Eventually, I performed the Meditation on a Curtis Institute of Music faculty concert. The teenage student who once attended Curtis was now a violin teacher at the very same school. The Meditation was programmed within a group of once popular salon pieces but now largely forgotten. Victor Herbert’s “A La Valse” came to an end, the applause died down, and the Meditation’s two introductory bars rolled, harp-like, off the graceful fingers of pianist, Billy Sokoloff. I cannot tell you whether on that particular evening I was a poet or even a reasonably successful teller of Thaïs’s story. Such things are mysteriously opaque to performers. You would have had to ask the people attending the concert. As the Meditation progressed, a violinist in the audience, Linda Cerone, turned to her husband, David, who was then a member of the violin faculty, and whispered in his ear dreamily, “He’s playing his old records.” David, who has his own cherished record collection, lowered his eyes and smiled knowingly.

Was I a poet? The Curtis Institute records all faculty concerts, and somewhere in their archives lurks evidence of my performance to which I could easily gain access. One listen and the question would be answered, but I’m apprehensive about what the truth might reveal. Better that some Curtis student delegated to cleaning out the school’s musty basement years into the future stumbles onto my recording and wonders whether he should listen to Steinhardt, dead long ago, playing the Meditation. Let that student decide whether I was a poet or not. Let him be accused of playing his old records.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

I’ve played the Meditation twice for an audience now and will play it again very soon. I’m always looking for new insights into the piece or stories so I can understand it better and perhaps play ot better. I haven’t found very many. I get the feeling Meditation is not as appreciated as it should be, as you wrote. When I saw that you wrote a post in it, I was unbelievably too happy for words. Thank you so much, Mr. Steinhardt, for writing this. I wish I could hear your interpretation, but sadly I’m no Curtis student. I can’t wait for your next post.

When my father was well into his 90s (he was born in 1909) he still loved to retell the story of himself as a young teenager going to hear Fritz Kriesler play a recital at Cleveland Public Auditorium. As he recounted how beloved Kriesler was by his audience, chairs even set on the stage around him in that huge auditorium, not letting him off the stage until many encores were played, my Dad would begin to weep. Such was the effect of Kriesler’s beauty of tone and intimate connection with his public. My Dad was an accomplished “amateur” violinist who loved listening to and especially playing “Meditation” from Thais. The fourth generation of violinists in our family will be learning that venerable warhorse soon, I’m sure. Thanks for the tribute.

Mr. Steinhardt,

What an information-packed and moving reflection on the Meditation. Beautifully written. As badly as I play it, the piece has a transcendent quality that comes through. I beat it up but it takes flight nonetheless. Its soul is unmistakably French and that’s another one of those things we are also not given to understand. You are now at age when medication has turned to understanding or, to put it in Emersonian terms, when Understanding has turned to Reason.

Al Rosa

mr Steinhardt, I am just a beginning fiddler, but I loved your books. please write another one.

Thank you so much for sharing your poetic thoughts! I too used to not want to play Meditation. And now after getting older and playing so many years of opera, I have changed. I also enjoyed remembering Francais’ shop. And you have inspired me to go retrieve my grandparents’ old 78s. Thank you!

Beautiful writing.

Leave a Comment

*/