An Arthurian Tale

May 8, 2018

As a teenager growing up in Los Angeles, some fifteen years before our Guarneri String Quartet would perform and record with the pianist Arthur Rubinstein, I had a brief preview of Rubinstein’s personality. My violin teacher, Peter Meremblum, had founded and led a very well-known young people’s orchestra in which I played. The Southern California Junior Symphony had acquired enough quality and reputation to be featured with violinist Jascha Heifetz in the 1939 film They Shall Have Music. Meremblum seemed to know everybody in music and was able to lure some of these great artists to his Saturday-morning rehearsals.

Arthur Rubinstein appeared at one of the rehearsals. The news of his impending performance traveled quickly and instead of the usual handful of parents and friends attending, the hall was now filled to overflowing with music lovers and curiosity seekers. I had already heard Rubinstein perform memorably at the Hollywood Bowl, and had listened to him avidly on recordings, but this was to be my first encounter with such a towering artist up close.

Everything about Arthur Rubinstein was striking: his shock of curly hair, his prominent nose, his husky voice, his grace, his poise, as he shook Meremblum’s hand and greeted us in the orchestra. But when Rubinstein sat down and began to play the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto, even we youngsters could tell that he was struggling with passages that came out blurred and somewhat uneven. Suddenly, Rubinstein stopped, rose from the piano, and addressed us. “I want to apologize for my playing. Last night I smoked too many cigars,” he said with a conspiratorial wink, “had too much to drink, and stayed up far too late. What I really need now is not the Tchaikovsky Concerto but two aspirins and a good snooze.”

There was complete silence in the orchestra as we tried to digest what Rubinstein had just said. More than merely a great pianist stood before us: a person of stature who could admit his shortcomings and even apologize to kids, some of them with acne sprouting on their faces, was indeed a great man. With his confession, a cloud seemed to lift off Rubinstein. He resumed his place at the piano and played the Tchaikovsky Concerto with an electricity and verve the memory of which all of us present will carry to our graves. It was beyond my imagination to think that I might be playing chamber music with Rubinstein little more than a decade later.

When our Guarneri String Quartet formed in 1964, we had no concerts arranged, no manager, and not even a name, but good fortune quickly shined on us. In addition to acquiring all of the above, we soon landed a recording contract with RCA records. Our recording producer, Max Wilcox, also happened to make records with none other than Arthur Rubinstein.

During the year that we recorded the Beethoven cycle for the first time, Max began to scheme. Rubinstein visited the RCA studios regularly to record and listen to the final edit of new recordings. He was pleased with the final version of his latest solo disc, Beethoven’s C Minor Concerto, which Max was now playing for him. While Rubinstein leaned back and lit up a very good cigar, Max gently asked whether he might like to hear the newest recording of a gifted young quartet in the RCA stables. Perhaps in his next life, Max will be a professional matchmaker, for after listening to us, Rubinstein proposed that he, a man already in his eighties, and the youthful Guarneri Quartet join forces for the Brahms Piano Quintet.

Such a collaboration was something none of us would have dared to imagine. We were young and at the beginning of our career, while Rubinstein, one of the most renowned pianists in the world, was in the twilight of his. With such a disparity in age, culture, and experience, it was hard to predict what the chemistry would be like.

At our first rehearsal for the planned recording, Rubinstein himself ushered us into his New York City apartment. It was the same Rubinstein who had appeared before our children’s orchestra, only now his hair was almost white. For an eighty-two year-old man, he exuded a seemingly unquenchable vitality, keeping up a stream of convivial conversation as we entered a well-appointed room with a grand piano featured prominently at one end.

It was quite impossible to forget the stature of the man with whom we were about to rehearse. On the other hand, there was none of that discomfort one feels in the presence of a powerful personality who has attained the very top of his profession. A big ego was obviously at work, but we soon learned that Rubinstein’s interests extended outward beyond himself and music into art, literature, politics, the world, and with a charm and intelligence that were all but irresistible.

Three truths were immediately evident as we began to read through the Brahms Quintet for the first time: Rubinstein was not very well prepared, he seemed somewhat cavalier about whether we played exactly together, and his playing was exquisitely beautiful. His phrasing had a leisurely sweep and suppleness that was never forced or excessive.

As we soon learned, Rubinstein was an astonishingly fast learner, but he seemed blithely unconcerned with wrong notes and occasional uneven passages. It was the music itself that absorbed, even intoxicated him. He would often stop and exult over a harmonic progression, a special moment.

That, in turn might remind him of a story. Starting the tale seated at the piano, he would become animated and stand up to act out the various plot twists and even assume the voices and facial expressions of its characters who were often some of the leading musicians of the turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century. Rubinstein demonstrated the punch line of a long tale about a famous pianist with a drinking problem by walking shakily to the piano, bowing with exaggerated dignity to the audience (in this case, the four of us), and then turning around and pretending to retch violently into the piano. We were an adoring audience, happy to be in the presence of this extraordinary raconteur who for those brief and delicious moments ushered us into a world that had long since vanished.

An enormous bonus came with Rubinstein’s music-making. We were able to witness up close an artist who seemed to enjoy himself and every aspect of his life immensely. He once said that even a toothache gave him pleasure! Really, Mr. Rubinstein? On the presumption that even the most joyous people have an opposing, balancing dark side, I would secretly observe him for signs of it as we listened to playbacks of sections in which Rubinstein had not played his best. But I could find none. He took it all in attentively; his attitude was relaxed, unworried, confident.

Rubinstein stood out as an eighty-year-old experiencing the autumn of his life with the freshness of a child. And it showed when he played. There was a grandeur and expansiveness in Rubinstein’s phrasing. He grasped both the scope and the details in the music and took the time necessary to reveal them.

Our Guarneri Quartet and Arthur Rubinstein eventually performed in New York City, London, and Paris, and recorded ten different works together—the Brahms, Schumann, and Dvorak Piano Quintets, the three Brahms Piano Quartets, the Dvorak E Flat Major Piano Quartet, the two Mozart Piano Quartets, and the Fauré C Minor Piano Quartet.

I always hoped that, by osmosis, some of Rubinstein might rub off on me. It would be foolish, of course, to think that one person’s artistry could be grafted onto another human being. I would settle for something more modest, a small portion of his outlook on life. When you are blessed with such an attitude, all things are possible.

Our paths crossed with Rubinstein some ten years after first performing and recording with him, again at RCA. The Guarneri Quartet was making another record and Rubinstein, now well into his nineties, was there to hear one of his very last recordings. Rubinstein stood, immaculately dressed in a dark blue three-piece suit, with an antique gold watch fob emerging from his vest. Aged and frail, but still a fashion plate, he greeted us. “You know,” he said almost apologetically, “I never imagined reaching this advanced age.” A sheepish smile flickered across his face. “Frankly, I feel silly being this old.”

That endearing little remark about aging brought me back to the moment when Rubinstein had stood before us youngsters those many years earlier and said, “What I really need now is not the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto, but two aspirins and a good snooze.” Both remarks were so disarmingly honest, even confessional, as if Rubinstein were letting each of us individually into his own very private and personal world.

His playing was like that. Let me tell you a story Rubinstein seemed to say as he spun out phrase after magic phrase.

And what a story it was.

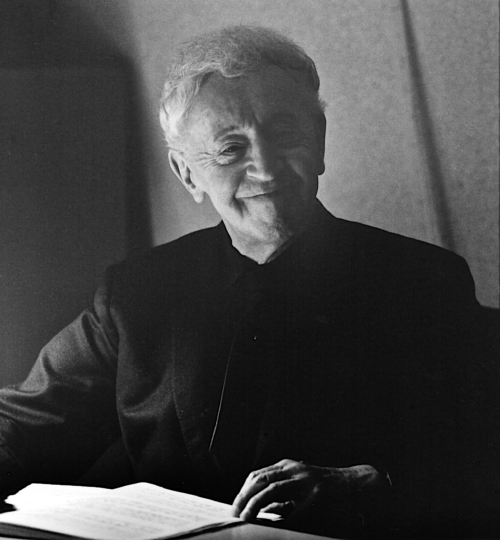

Arthur Rubinstein(a),1971 Photo © Dorothea von Haeften

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

Arnold, I just love your stories so much. Would you consider sharing some memories of Max? Or maybe something about the relationship between an artist and his producer? Dick Stoltzman

Arnold, I just love your stories so much. Would you consider sharing some memories of Max? Or maybe something about the relationship between an artist and his producer? Dick Stoltzman

The last time he played a recital in Boston, Symphony Hall was packed to overflowing, with people crammed onto the stage. Rubinstein entered by the upstage door at the back back. There was a little girl in a pink satin dress sitting on that central aisle leading from that door to the piano, perfectly behaved and attentive. After the last encore, she received her own private, courtly bow as he left the stage for the last time. I suspect that child will carry that memory for life, as I have.

Great story, thanks for sharing. You’d be just the perfect passenger to seat next to in a long flight… :)

Thank you for this wonderful story of a great pianist and a great string quartet. At the end of the day, our humanity shows through even for such talented and gifted musicians and people.

The Brahms recording remains one of my favorites.

So if we trawl through the Mendelssohn last mvmt done with intense panache and the vocal solo from the little girl done with intense coloratura, will we see a juvenile Arnold there in the rank-and-file?

Just finished listening again to the quartet’s recordings with Rubinstein on CD. Wonderful collaborations. In April 1961 I was fortunate to hear Rubinstein in solo concert at Connecticut College in New London, Connecticut. Also enjoyed both of his farewell concerts in Vancouver, BC.

Thank you Arnold for yet another warm,endearing and funny story. I feel I there when he retched into the piano. My kind of joke! Arthur Rubenstein was my father’s favorite pianist.

ps. the photo by Dorothea is marvelous..

Arnold, as usually, you always write a wonderful story of your violinist career with such so incredible musicians like A. Rubinstein. I love your stories and expecting them every month..

Love, Maru Rangel

It is so good to be visiting one of your stories again. You have such a way of invoking the

magic and excitement of yesteryears, reminding me of meeting you, and Michael, listening to rehearsals at Marlboro with Pablo Casals, and the exquisite pleasure of listening to the Guarneri Quartet.

The Brahms recording was also Glenn Gould’s favorite recording.

But, Arnold, all the wonderful qualities of Rubenstein that you describe so well here, could be said about you. And have been said about you: Your grace, your humor, your thousands of fabulous stories, your love of music, your brilliant talent, and your humility, your ability to confess and laugh at yourself… it’s all you. (Sorry, Arnold, I know this will embarrass you, but it has to be noted).

Powerful statement… about Rubi and also about yourself. Thanks for sharing.

Leave a Comment

*/