Fifteen Seconds of Fame

December 1, 2014

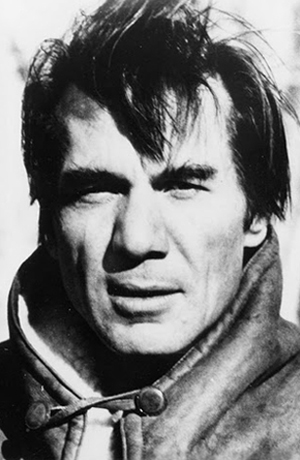

Galway Kinnell

The American poet, Galway Kinnell, died last October. I had the pleasure of knowing him and seeing him occasionally during the years he lived in New York City. One evening, Galway and his wife to be, Barbara, invited me and several other friends to dinner. Introductions were made all around and a superb meal along with lively conversation soon followed.

At one point, knowing that I was a musician, a woman seated across from me asked whether I had ever met Igor Stravinsky. I had, indeed, met the composer, but I told her the encounter had been so utterly minor that it really wasn’t worth repeating. She persisted. For whatever reason, I could see she was intrigued by Stravinsky, and so, reluctantly, I told my story.

When I was twenty-one years old, William Steinberg, the conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, invited me to perform the Stravinsky Violin Concerto with his orchestra. Of course, I accepted.

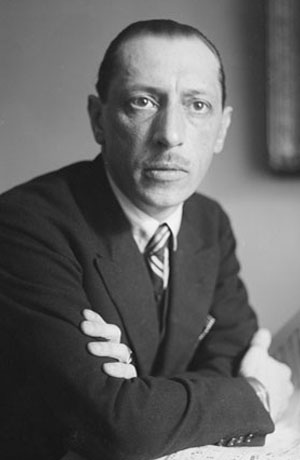

Igor Stravinsky

This was a very important engagement. What Maestro Steinberg didn’t know was that I had never heard, much less performed the Stravinsky Violin Concerto. Several months before the performance, I began to worry in earnest. Even more than simply learning the concerto’s notes, challenging as that might be, I was concerned about my ability to grasp the elusive character of Stravinsky’s music.

That summer, while in Los Angeles, my hometown, I happened to run into Sylvia Kunin, a great supporter of young musicians in the area. I asked her whether she knew anyone who could help me with the concerto. Sylvia said she would think about it and get back to me.

That afternoon, Sylvia called my parents’ house and told me she had found someone. Igor Stravinsky. I almost dropped the phone. “Here’s Stravinsky’s phone number,” she said. “He’s waiting for your call.

My head began to spin. The idea that Igor Stravinsky, arguably the most renowned composer on the planet, was waiting for a call from inconsequential me, was an impossibility. That Stravinsky even had a phone, just like ordinary mortals, also struck me as an impossibility.

Nonetheless, with shaking hand, I dialed Stravinsky’s number. “Hallo,” a voice answered after a few seconds. It was Stravinsky himself. I blurted out my name and began to state the purpose of my call, but Stravinsky gently cut me off. He told me he was too busy to devote any time for his older music but that I should come over to the house and he would give me a record of the concerto made years earlier with the violinist Samuel Dushkin. Stravinsky then gave me his address.

“Mom,” I said to my mother who was in the kitchen, “I’m taking the car and driving to Igor Stravinsky’s house.” Mother refused to believe me at first, but then insisted on sitting in the car in order to watch the revered composer open the front door and let me in. Stravinsky greeted me very personably, handed me the record of his concerto, and said that I could keep it as long as necessary but that he wanted it back since it was his only copy.

We shook hands and I left, record in hand, my head in a daze.

The record proved extremely useful in helping me absorb the concerto’s playful yet quirky style, but eventually the time came to return it. With trembling hand, I again dialed Stravinsky’s number, and again a voice on the other end said, “Hallo.” Within minutes I was back in Stravinsky’s house returning his record and thanking him. I was so unnerved by the experience that I left without even having had the presence of mind to ask Stravinsky for his autograph.

“And that’s my utterly insignificant Stravinsky story,” I told the guests seated around the dinner table.

I cannot vouch for the accuracy of what follows since the dinner party took place many years ago. I apologize for any tricks my memory may have played on me.

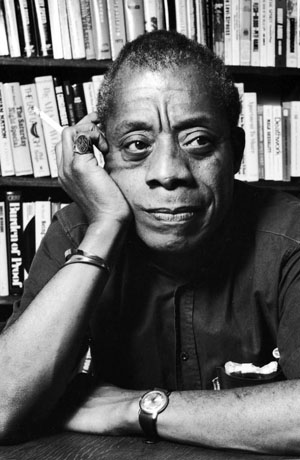

James Baldwin

There was a moment’s silence, and then the writer seated next to me said that she had an equally insignificant brush with greatness to relate. “I was still a relatively young writer, and working as a publishing house editor,” she said. “One day, the president of the company announced that James Baldwin would pay a visit to the office the next morning. I was so excited I hardly slept a wink that night and woke up with a horribly stiff neck. Hours later, I sat stiff as a board and miserable at my desk, wondering how on earth I was going to greet my hero with an immovable head glued to my body. But to my astonishment, when the president introduced me to the famous writer, Baldwin gushed something like, ‘Why young lady, I’ve read some of your work and I absolutely adore your writing. You are enormously gifted.’

“At that moment, my heart melted, and so did my neck muscles. I lifted my head effortlessly and thanked him. The encounter had lasted less than a minute, but my stiff neck had vanished.”

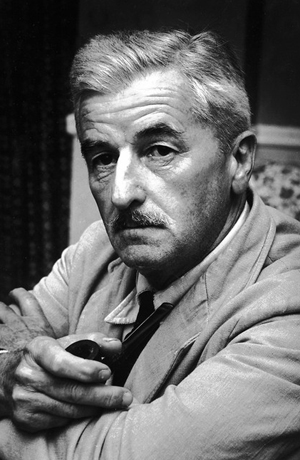

William Faulkner

Then another writer at the table chimed in with a similar story. He said that as a very young man, he had briefly worked as the telephone switchboard operator of a hospital. One evening, none other than William Faulkner was admitted. Later that night, Faulkner’s room lit up on the switchboard and he asked to be connected to a certain telephone number. Our fellow dinner guest said that he had had the thrill of saying exactly three words to one of the greatest American writers: “Certainly, Mr. Faulkner.”

“I have my own Faulkner story,” Galway exclaimed. Galway told us that he was on a Fulbright scholarship in Paris, France, when it was announced that William Faulkner and Albert Camus would be giving a talk together about their lives and work. On the appointed evening, the two writers took their seats on stage accompanied by another man who told the audience that, unfortunately, the translator had become ill. He asked whether anyone would volunteer to translate between French and English.

Albert Camus

“I raised my hand and suddenly found myself on stage with Camus and Faulkner,” Galway related. “Camus began the conversation: ‘Please tell us, Mr. Faulkner, what the state of American literature is at the present moment.’ I translated.

“Then Faulkner answered, ‘How the hell should I know anything about American literature. I’m just a farmer.’ This time I did not translate, at least not exactly, and for the rest of the evening I felt obliged to edit as best I could Faulkner’s unpleasant remarks. Camus and Faulkner thanked me afterwards with a dismissive handshake and then, poof, they were gone.”

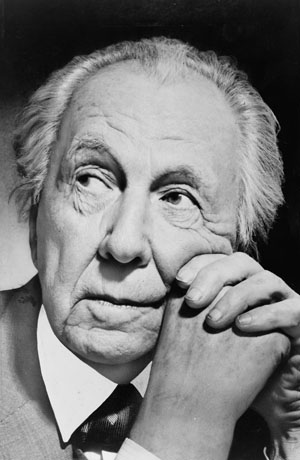

Frank Lloyd Wright

“I’ve got a story somewhat like that,” said the architect seated next to Galway. He told us that Frank Lloyd Wright had once visited his class in architecture school. After seeing several student designs, the elderly Wright launched enthusiastically into an impromptu lecture during which he absentmindedly sat down on one end of a door that had been temporarily placed on two saw horses.

“Seeing that Wright was oblivious to the danger of the door tipping over with his added weight and to the possibility of suffering a bad fall, I sat down on the other end of the door,” the architect explained. “Wright never missed a word and I, a mere student, had the anonymous satisfaction of having possibly saved the great architect a trip to the hospital”.

Eleanor Roosevelt

“Well, I have my own trifling story to tell,” said the woman who originally asked me about Stravinsky. “Eleanor Roosevelt had been invited to speak at my college, and as a member of the student welcoming committee, I was chosen to pin a corsage on Roosevelt’s lapel as the First Lady walked on stage. I was so nervous and my hands shook so badly that I stabbed Mrs. Roosevelt in her breast with the corsage safety pin. I was mortified, but seeing how upset I was, she consoled me and told me things like that had often happened to her when she was young and had to appear in public. Mrs. Roosevelt didn’t even know my name, but I’ll never forget her kindness.”

The man next to her, yet another writer, stirred in his chair and we all looked expectantly towards him. One by one, Galway and each of his guests sitting around the table had served up their utterly insignificant brushes with greatness and now it was his turn, the last guest, to speak.

“Yes, I too have a story you might want to hear,” he said. “The student literary club at my college had invited Dylan Thomas to read at their monthly poetry event. As president of the club, my job was to pick Thomas up at the train station and make sure that he, an infamous alcoholic, would stay sober.

Dylan Thomas

“I failed miserably,” he told us. “Thomas insisted on going directly from the train station to the nearest bar, and demanded that I keep him company. After a couple of hours of drinking, he announced out of the blue in slurred speech that he had a wonderful new name for our student literary magazine, doubtless one far better than the unimaginative name now adorning its cover.

“For the first time, I saw the possibility of something positive emerging from Thomas’s visit,” the writer said. “He might make a drunken spectacle of himself at the poetry reading that evening but our little literary magazine would be able to boast an evocative name bequeathed to us by one of the world’s greatest living poets.

“Dylan Thomas lifted his head in an alcoholic haze and said, ‘The word I have in mind for your magazine is’—and here he smiled at me ever so sweetly—‘the word I have in mind is…Scrotum.’”

We all burst out laughing, and someone at the table proposed a toast: “To the journey we have just taken from Stravinsky to Scrotum, and to a future with many more utterly insignificant encounters.”

If my memory serves me correctly, dessert was then served.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

Just loved this!!

I intend to use this story telling episode as a new dinner table conversation piece. Everyone will be asked to tell their 15 seconds of fame experience. I already have mine. I had dinner with Arnold Steinhardt and Dodo. Who can beat that?

Actually, Faulkner could speak pretty reasonable French….God knows why.

What a delightful way to travel around the table!

When I was ten years old, Jascha Heifetz played with the Miami Philharmonic. From the first notes of the Beethoven concerto, which I recall to this day over 60 years later, I was mesmerized. After the concert I went backstage for his autograph in a little book in which I kept a record of special events and people. The guard at the door warned me, “He doesn’t like children.” Heifetz’s demeanor, of course, was not exactly warm and inviting! However, my heart must have been in my eyes — he looked at me for what felt like forever, smiling very slightly, and then went through my entire book, page by page, before signing it.

My own “utterly insignificant brush with greatness” occurred in front of an exclusive men’s tie shop on the corner of New York’s 6th Avenue and 50th St. in the 1960s. Among the richly configured goodies displayed in the window, what caught my eye was a crushed velvet tie of a most delectable purple hue. As I waited patiently for my now tardy friend, along came the great Surrealist painter, Salvatore Dali, wearing his customary mustache and a magnificent tan camel’s hair coat. As he passed the shop window, he was attracted by that same tie and spent a long couple of seconds drinking in its lusciousness. Being more than a fan of his work, I was tongue-tied – what do you say to an idol; “Hello, Mr. Dali, I love your work”. . . duh? No, after he left, along with his two gorgeously attired female companions, I did the only thing possible; I bought the tie immediately and have treasured it ever since.

wow, Amazing stories!!!

So funny…..thanks for sharing this lovely vignettes with us!

Best Dylan Thomas story I’ve heard ! – and the perfect gathering – when accomplished artists speak of their own helpless love for their beloved teachers/heros – my own favorite encounter was with Stephen Spender, I do not do such encounters well, as he was in his 80s, and I was young and careless, wondering with him about the relationship with language, Spirit and age – he replied generously – but now that I am of his age, I feel my youthful arrogance was way out of line. Still! These precious moments!

It wasn’t enough that I got to watch Vladimir Horowitz rehearse at Carnegie Hall, peeking through the balustrade of the dress circle (along with probably a dozen others like me in the dark, I learned later) and got to see Wanda Toscanini lose it over some chairs that had been carelessly left on the stage. I wanted to meet him. So, as coached by his piano technician, my spouse and I dropped by his 14 E 94 townhouse one day at 11am to give him a copy of my Steinway poster, hoping, of course, to meet him. A housekeeper let us in and phoned upstairs. As we waited, we heard some unintelligible volodyistic vocalizations up the spiral staircase. Wanda came down to meet us, not livid at the intrusion, but in fact very earnest and polite. We couldn’t meet him though, Wanda explained, because “Mr Horowitz is not visible at the moment.”

What a legendary evening! Great stories.Thanks so much for telling us about it all.

In 1978 I was taking the Metroliner from Washington DC to NYC. On walked Arnold Steinhardt, 1st violin of the renown Guarnari Quartet, violin case in tow. I was sitting with my wife and I told her who he was. He was sitting alone, and I went over to talk to him because I was a fan of the GQ and also a cellist. The GQ had played the night before at the Carter White House. I told Steinhardt I was a medical doctor, originally from LA but now living in the SF Bay Area. He told me that when as young boy in LA he had seriously considered medicine but decided against it because he had a poor memory. “Really,” I said. “Can you play the Beethoven violin concerto from memory,” I asked. “No problem”, he said, “but that’s different.” Interesting how we conceive memory. That was my brief moment with our maestro.

Arnold, as I’ve come to expect, your stories & writing are what I want to share when able. I was saddened to hear of Galway’s passing, tho I haden’t read his work for 40 years, remember, stil, homophobicthe feelings when reading his work. Brushes with fame, poets, my daughter, at 3 yrs. was asked to sit with Allen Ginsberg during a reading in Berkeley, Ca.

I had the privilege of studying poetry writing with Galway Kinnell at Sarah Lawrence College where I was an undergraduate, Class of ’74. A friend recently asked about him and this is what I wrote to her:

So what was Galway like, you ask. I learned a lot from him. For one thing, I learned that it is good for poems to be serious, to put yourself out there, to express what’s important. He was a brooding presence but very gentle as a critic. He made you want to write more (the key sign of a good teacher) and never insulted anyone. He wasn’t interested in discouragement and would point out the lines that he liked (but only if he found lines he liked). He would of course have us bring our own stuff to the seminars and we would read them out loud and criticize them. He also would have us bring poems that we read and liked and it didn’t matter from what style or time. I brought in some poems by Ted Hughes from his book “Crow” which was new at the time. Galway didn’t admire them–they were too negative for his taste. But when someone pointed out a line or two as though to suggest they weren’t any good, Galway said, “They look good to me.” I worked on the poem “My Mother’s Death” with him (parts are on my web site). Of me Galway pointed out to the group that when they criticized my poems they never criticized my technique, that is I didn’t write sloppy lines. It was always whether the composition held together. He taught me also that poems are meant to be read out loud. I also remember bringing in a passage from Samuel Beckett, I forget from which novel. Galway didn’t like that much either — he thought Beckett’s language was “dead.” I continue to disagree.

When I taught violin in the English schools I personally studied violin. My teacher, Clifford Knowles, loaned me his score of the Elgar Violin Concerto when Yehudi Menuhin was to perform it with the Halle. I could afford a seat three rows back from center stage and there I sat with the open score throughout the marvelous performance. At the Concerto’s end it was obvious that Yehudi Menuhin bowed to me. At backstage he was so kind and gracious.

Leave a Comment

*/