Improv

February 8, 2021

Shortly after my first teacher taught me, age six, the basic positions of the violin, he placed a page on my music stand with what appeared before my innocent eyes to be groups of lines with indecipherable black dots scattered willy-nilly over them. He then explained that these groups of five lines were called staves, that the black dots represented musical notes, and that once I learned to read those dots, a magical world of music would open up for me.

I don’t remember learning how to read music, but my teacher was most certainly right. In unlocking the secret of those little black dots, I was able to revel in modest melodies at first, then slowly move on to music of every shape and size, and finally to some of the towering masterpieces of the musical repertoire.

In exclusively reading music, however, I missed out on another magical world, and one that every baroque player, every country fiddler, as well as every jazz musician must know—the art of improvisation.

Not that I missed improvisation as a student wading through the repertoire put before me. The inspired music of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and on and on, left me little time to think about a world devoid of black dots. Even the tradition to improvise concerto cadenzas on the spot—something that any decent eighteenth- or nineteenth-century soloist would have been capable of—was dismissed as unnecessary in my twentieth-century musical education. Why would I even consider improvising a cadenza if most concertos came with cadenzas already composed by violinists of the past? For example, I have a collection of no less than twenty different cadenzas written for the Beethoven Violin Concerto. The era in which soloists such as Mozart and Beethoven masterfully improvised their own cadenzas during performance is, with rare exceptions, sadly behind us.

Only once during my days at music school did several of us conjure up, more as a joke than anything else, a fictitious figure we called Ernst Markevitch. The idea was to fool unsuspecting listeners into thinking that our improvisations, in what I recall as a vaguely mid-twentieth-century style, were the work of Markevitch, as yet unknown but destined to be one of the greats. It was fun to improvise. You could be tender one moment, dramatic the next, and furiously virtuosic at any time in between. The sky being the limit, the joke of it all tended to dim as we liberated our subconscious ideas and feelings. My brother, Victor, having the advantage of being a composer himself, went so far as to program Ernst Markevitch on some of his piano recitals, prefacing the performance with a mini-lecture on Markevitch’s quirky background. I believe he described Markevitch’s father as the captain of a Liberian freighter, his mother a prostitute en route as a passenger to a new and more proper life.

Poor Ernst Markevitch’s life basically came to an end with my graduation from music school. For the next sixty years, I immersed myself happily and gratefully in the life of a working classical musician. There were many black dots to master, interpret, and exult in. Only in listening to jazz live or on record would I admire the breathtaking, on-the-spot imagination of those musicians, and have a momentary pang of regret that this world of improvisation was closed to me.

Then, late in life, my wife Dorothea and I moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico. A new land, a new culture, and the possibility of new friendships awaited us. I soon met Judy Tuwaletstiwa, a lovely person and a remarkably gifted visual artist, writer, and teacher. At dinner one evening, we immediately bonded over shared interests, but also in a sweet way through a common birthplace in Boyle Heights, a section of Los Angeles. Judy and I traded stories about growing up there, about politics, and inevitably about our shared Jewish heritage. And, apropos of that heritage, Judy told me about a particular work of hers, “Das Buch der Frage” (the Book of Questions), which she would be including in a planned show of her works at the Center for Contemporary Art in Santa Fe.

The triptych Judy had created, three large, evocative panels, had been inspired by an iconic photo of a young Jewish boy with hands upraised who had just been driven out of the Warsaw Ghetto along with many others by the Nazis. I remembered having seen this heart-wrenching image more than once over the years. The photo, one of forty chronicling the destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto, was taken by a German photographer who proudly presented it in a leather-bound album to Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS and a key architect of the Holocaust. The work’s title, “Das Buch der Frage,” referred to a remarkable book published in 1987 asking probing questions that defied easy answers. Certainly, one such question on Judy’s mind as well as mine would be how a just God could allow the Holocaust, and specifically the almost certain death of this young boy.

Judy Tuwaletstiwa, Das Buch der Fragen (triptych), 2007-2013, burned holes, linen and camel hair, paper, llama saddle, graphite on canvas, 72 x 48 in each.

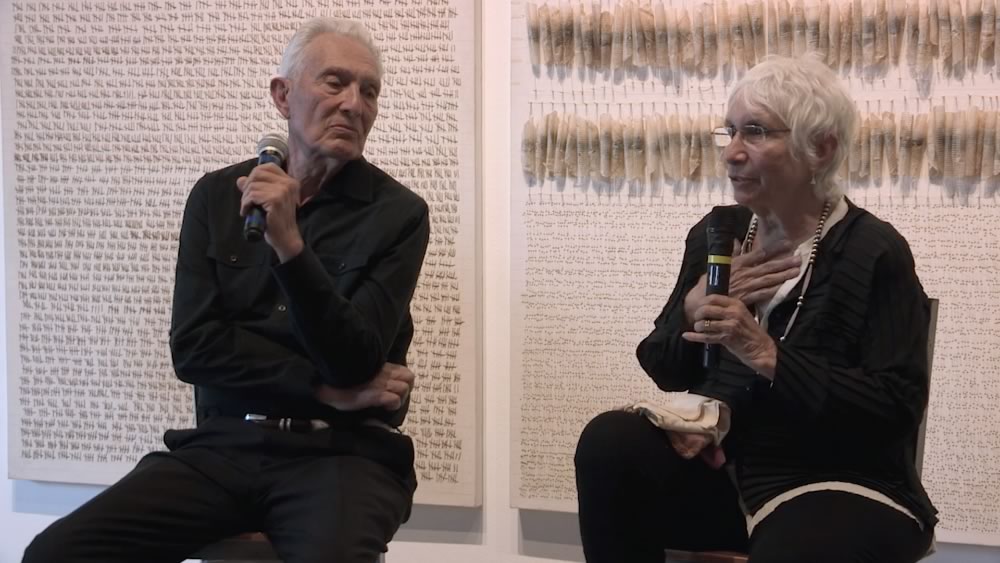

As the evening wore on and our conversation about such things as art, music, the Nazis, and the Holocaust rose to an ever more absorbing level, Judy suddenly turned to me and asked whether I would be willing to talk with her about these subjects, and the triptych, in front of an audience at her exhibit. Judy by nature is questioning, probing, intense, and yet with humor that shines through the most serious of subjects. I agreed immediately to the talk. Based on what had just transpired at dinner, I was sure that a conversation with Judy would have to be, at the very least, stimulating.

Detail from Das der Fragen

But then Judy asked yet another question. “After our talk, Arnold, would you be willing to improvise music on your violin based on ‘Das Buch der Frage?’” There were so many obvious reasons to simply say no. I had retired from performing two years earlier. I had no experience improvising in any shape or form—that is, except for the imaginary creations of Ernst Markevitch. And I could easily make a fool of myself in public attempting something of which I had not the slightest expertise. Perhaps too much wine had gone to my head, but the significance of the subject at hand and Judy’s moving triptych influenced me, and in some scatterbrained way I regarded this as an adventure and a chance to expand my musical horizons. So I said yes.

Judy of course was delighted, and, as the effects of the wine began to wear off, the appropriate alarm bells in my brain did not go off, and I did not say to myself, “Arnold, what on earth have you gotten yourself into!” Instead, it seemed like an opportunity to delve into the essence of Judy’s art, to ask questions that might not even be in “The Book of Questions,” and in some sense to also ask them while improvising on the violin.

How does one learn how to improvise? The only answer I could come up with was simply to dive in. With more-or-less two months before the planned event, I set about practicing improvisation every day. Along with my usual work, I reserved a few moments to let my fingers do what they might on the violin. Inevitably, the poignant vision of that young boy, hands upraised, hovered over me. The first sounds out of the violin had a deep melancholy to them. Then I thought about Judy’s triptych. She had originally planned only one large panel covered with the groups of five lines. Why not possibly insert five-note figures representing those lines into my improv? Judy eventually decided to add two more panels to her work. Should my creation then be in three sections, possibly with a focal point somewhere in the middle? Perhaps I could steal for that purpose the mournful melody my musically untutored grandfather had made up in Poland a century earlier. Then there were the uncountable emotions elicited by both the triptych and its inspiration to consider. I delved with my violin into sadness, anger, rage, desperation, thoughtfulness, and resignation without any idea at first how they might create a storyline.

As the weeks went by, my discomfort at attempting something so new vanished and I found myself looking forward to the dizzying, high-wire act of inventing notes and phrases out of thin air. I began to loosen up, to give myself the freedom to roam, to run into dead ends, to entertain clearly wacky ideas, and to come up with concepts that proved interesting but as yet without a place to put them. Something I conceived of for the center would occasionally pop up more successfully toward the beginning, without my even consciously willing it. I saw some purpose in crafting an overall form with musical signposts along the way—this section tender, another dramatic, yet still another full of anguish—but how to stitch them together in some kind of coherent fashion eluded me. Not only that, the improv became longer and longer as new ideas entered the scene. Why not play the repeat of the same notes an octave higher? Or suddenly go from major to minor key? Or have that passage stop dead in its tracks and have the silence be the music? Yet, I couldn’t say that the music began to take more than a vague shape over time because, by the very nature of improvisation, it changed with every practice session.

The day of reckoning finally arrived a year from last July. Judy and I had a long and animated conversation in front of the assembled audience, and then I picked up my violin and improvised for ten or fifteen minutes facing both “Das Buch der Frage” and the haunting photo placed next to it of that young Jewish boy.

I once asked my friend, the country fiddler Mark O’Connor, what it felt like to improvise. He told me that at its best it is an out-of-body experience, and feels almost as if he is levitating.

Did I levitate during my improvisation before “Das Buch der Frage?” No, my feet never left the ground. But at times the out-of-body feeling that Mark talked about took hold of me. Making my way through the improvisation, I had the odd sensation that I was not completely in charge, and that the improv genie had been let out of his bottle in order to direct me.

Judy, evidently pleased with our “Das Buch der Frage” encounter, has suggested we think about doing it again in one form or another. I’m more than willing, but it is unlikely that my improvisational skills will improve enough for me to levitate. I’ll be happy enough if, along with the inspiration provided by Judy’s moving triptych, I can lure the improv genie out of his bottle once again.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

I have written before of my great admiration of your playing and your writing. I am also a great admirer of Judy’s, a close friend of my niece, Catherine Ferguson. To add to my feeling about this, I am a German born Jew, escaping in October of 1938 with my family, and settling in San Francisco in time for first grade. Say hello to Judy for me.

SO moving and inspiring. Thank you!!! ??

While reading the story I wished that I were there so I could hear the piece. What I nice surprise that my wish was answered. The music was both sad and beautiful and a fitting response to the art work. Bravo!!

Wonderful story! Thank you!

madge.briggs32@gmail.com

Very moving story and wonderful to have the video included. I found the Q&A at the end thought provoking and of particular interest. Thank you for your generosity in sharing your talents.

Thanks you….one of your most moving and fascinating blogs. The photo, the art work, your eloquent thoughtful comments, musical and verbal…..very special. And the improv….terrific. Loved it when you got warmed up.

Thanks, Arnold, for this improv story. I too love improv but it was not part of my musical career, although I always loved jazz, and probably did some when I was singing with my older brother, who couldn’t read music, playing the piano, always by ear. I’d love to have heard you improv.

Arnold, I have been making my way through this wonderful video, not yet at the improvisation (a virtual concert is about to begin where I live, and I’m in charge), but I wanted to tell you that I did hear the Guarneri from time to time over the years, but I have never known how to “go backstage” in a concert hall. Goodness, I heard Jaime Laredo a couple of years ago and didn’t know how to talk to him in that situation. (Decades ago, I spent Christmas Eve overnight with Jaime and Ruth Laredo in New York.) Anyway, I was worried about you when you didn’t write in that key of Strawberry over a period of time, and then so happy when all you did was move to Arizona and, presumably, stay healthy. I am grateful to be able to say something to you! Looking forward to hearing your improvisation…

Best,

Anne Tatnall from long ago

Thank you for this lovely reflection on improvisation (and other things!). I have been an amateur musician all my life, beginning as a violinist wed to those dots but morphing at the age of 14 into a jazz clarinetist. That out-of-body experience is a familiar one to me, particularly when playing with others. There was a time when I flinched from recordings of my own performances, too tuned to the wrong turns and squeaks that arise from quick course corrections, but lately, having reached the age of 78, I enjoy watching videos or listening to recordings of my playing, pleased and humbled by the new things that happen, mystified as to their origin. Music speaks through us!

that was such a special evening, arnold. and you write about your entry into improvisation so beautifully…i feel so fortunate to have heard you speak and to have listened to you play. levitation lived in your notes.

So nice to share your life and thoughts with you. I loved your improvisation, and the discussion that came before it.

The music, profoundly moving. The insights, quite terrifying. It’s almost a cliche to remark on how brief an interval there was in pre-WWII Germany from apparent high culture to utter depravity. How brief could be the interval between events close to home today and an unimaginably dark future? Thank you for the beautiful improvisation and for the generosity of both artists in sharing a long moment of reflection.

I really enjoyed the presentation of the Chamber Music Society and listening to the early recordings and hearing you and the others reminisce!! Lovely seeing you as well.

Margo

Leave a Comment

*/