Speak, Piano

March 6, 2017

Many years ago, my wife, Dorothea, and I visited her friend, Gottliebe von Lehndorff, in Peterskirchen, a town not far from Munich, Germany.

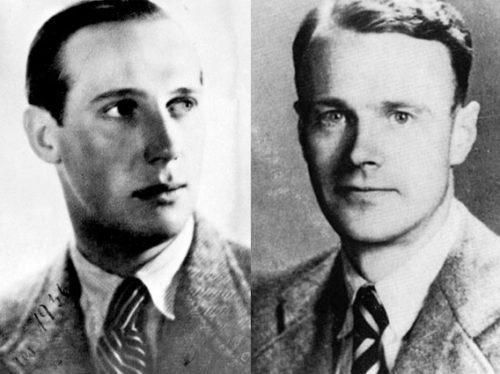

A single, shattering event had originally brought the two women’s lives together. Both Dorothea’s father, Hans Bernd von Haeften, and Gottliebe’s husband, Heinrich von Lehndorff, had been involved in the failed July 20, 1944 plot to assassinate Adolph Hitler, and both had been subsequently executed.

Heinrich von Lehndorff (left) and Hans Bernd von Haeften (right)

Gottliebe was now living in what was essentially a converted monastery. She had created a place where friends could live and where artists, writers, musicians, and assorted creative people could gather, converse, and expand on their interests. In my own field of music, the Austrian pianist, Friedrich Gulda, was a frequent visitor.

On the day Dorothea and I arrived, something unusual was taking place. Gottliebe and some of her friends had decided to relocate a grand piano, presumably the one on which Gulda and others played, from the second to the first floor. The plan was to move the piano out through a large upper window and lower it to the courtyard below. With this in mind, the piano had been tied with ropes that in turn were attached to a beam stretching across the courtyard. There were several people involved in this operation and they were all busily discussing the best way to proceed. The question was how to manage the ropes in such a way that the piano remained stable and unscathed on its journey first outward and then downward.

It quickly became apparent to me, even as a casual bystander, that none of those involved was a professional piano mover. Heated opinions flew back and forth for several minutes, ropes were rearranged again and again, and, finally, a course of action was decided upon. The piano began to be gingerly eased out of the window.

With hindsight, a professional should have been in charge, for the piano suddenly slipped out of a section of rope, careened into thin air, and then, with one convulsive motion, turned upside down. Some of us gasped, others screamed, and those non-professionals in charge pulled desperately on the remaining ropes in an effort to right the endangered instrument.

In all the excitement, I seemed to have been the only one who noticed a small piece of paper that fell from the still upended piano and fluttered gently to the ground. While the others successfully managed to lower the piano safely to earth, curiosity got the better of me. I wandered over to the square-shaped paper lying in the grass and picked it up. In utter disbelief, I saw that what I held in my hand was an image of Adolph Hitler sitting in a field and peeling an apple with his pocketknife. Hitler was wearing casual street clothes rather than a military uniform, implying that the photo must have been taken in the 1930s before the Nazis invaded the rest of Europe and set World War Two in motion.

Adolph Hitler looked so thoughtful, so benign surrounded by that bucolic countryside. Perhaps for many in the 1930s who had regarded this image—one that I soon discovered had come out of a pack of cigarettes—Hitler was indeed seen not only as thoughtful and benign, but also as the German-speaking people’s savior who would lead them to a new and glorious future. Now, thirty years after that devastating war, all of us gathered around the piano probably had Adolph Hitler still marauding painfully through our memories and our innermost feelings. Certainly, that must have been true for Gottliebe who had lost her husband, for Dorothea her father, for me many of my closest relatives in Auschwitz, and for all the others present both German and Austrian who were in one way or another ensnared by Hitler’s ghastly vision.

I showed everyone the photo of Hitler that had lived for decades hidden away somewhere inside the piano. It invoked outwardly nothing more than a few nervous laughs. Was the subject after all those years still too painful to dwell upon openly, or were people simply tired of their failed attempts to grapple with the incomprehensible?

I cannot remember whether I gave the cigarette card to anyone there or placed it back amongst the instrument’s innermost workings, but questions kept coming at me. Who was the smoker who had played this piano? Why had he or she not kept the card rather than squirreling it away? Was the smoker one of those brutal high-ranking Nazi officers who paradoxically also loved his Bach, Mozart, and Schubert? Could the person have been a terrified but apolitical music teacher seeking solace at the piano while trying to live below the dangerous Nazi radar? Or had this poor soul been a German Jew, smoking as he played, who loved his country and his music too much to leave in time to escape the extermination camps?

I’ve often wished that an old musical instrument—my violin, for example—could tell us its own vivid story as well as the one dictated by the performers who have played on it. For a brief moment, as the piece of paper fluttered to the ground and revealed its heart-stopping image, I almost involuntarily blurted out: Speak, piano. Tell us about the man with the pack of cigarettes. Tell us about the people who played Bach, Mozart, and Schubert on your keyboard in order to soothe their aching souls.

Tell us what you know about that dark and sinister time in human history.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

Thanks for this, and for all the previous, essays! Not to mention so much music to enjoy!

I also ask my violin the same kinds of questions but only once have gotten a glimpse of some of those answers.

A couple of years ago I had the opportunity to explore and document the history of a modestly famous Stradivari and the lives of those who had passed through its long life–almost literally back to the Cremona workshop. It was onstage when Brahms and Joachim premiered the Brahms concerto; it belonged to a former Auer student, later a mining engineer, who was exiled to Siberia as a young man and who very well may have sold the violin to cover the passage of his long-ago first love, so she could come from eastern Europe to the US; and it skipped town just ahead of Castro’s ragtag army…among other stories.

Really, if only these artworks could speak!

You never fail!! Touching and so visual.

Dear Arnold,

In the 1970’s I worked in Cologne Germany and often visited Berlin. The (West) German government office supervising banks and other credit institutions had its office in the building where one of its courtyards was then still pockmarked from the bullets that executed those who tried to kill Hitler.

The vast classical music culture scene was incomparable and I immersed myself completely. Since 1994, I’ve had the pleasure of heading the American Friends of the Berlin Staatsoper, whose orchestra, the Staatskapelle Berlin under Daniel Barenboim performed all the Bruckner symphonies at Carnegie Hall this past January.

Your recollections are wonderful.

Thank you!

Speaking of the intersection of music and war, my Uncle Leo, a clarinetist in a US Army band, was playing for troops stationed in France at the Eastern front when Hitler suddenly launched the Battle of the Bulge. In the confusion, he was handed a gun and told to march into the woods. At some point, he noticed that the soldiers to his left and right were German! Realizing the blunder, he raced back to camp just in time to catch the last truck back to the rear. Years later, just before Leo died, I got to play a duet with him, on my flute, all the while remembering that crazy but serious story.

Wars are full of such stories. In the Summer of 1944, my dad was a radio man on a B-24 flying out of England.

Right now it is the photo of those two heroes trying to save their country and perhaps the world that touches my heart. A picture of a happy Hitler does little for me.

Hi Arn,

Thanks for this fascinating story – I had no idea of Dorothea’s father’s part in that bitter adventure, and I hope you will convey to her my deepest sympathy. We wondered which of the photos was that of Herr von Haeften?

Looking forward to celebrating our birthdays in April, Dan

Speaking of instruments and war, when the Japanese invaded Manila after Pearl Harbor, a stray bullet somehow hit my aunt’s home and lodged in the beautiful dark Trubger piano she used to practice on in the living room. The family and piano survived the war; the piano was lovingly and carefully repaired and still stands proudly in my aunt’s home. As for my aunt, she went on to earn a Degree in piano performance, a DMA, and taught piano to countless students since then, all on that Trubger.

Dearest friends Arnold and Dodo:

Paolo and me are reading this story that moves us so deeply.

With love, from Ciudad de México. Looking forward to see you soon.

xoxo

I thought this was a particularly interesting story because I, too, lost relatives in the Holocaust, as did my husband. We are also quite friendly with someone else whose father was executed for involvement in the plot to assassinate Hitler. History is still very close!

Thank you for sharing harrowing historical

events, poetically expressed; as an

everlasting tribute to your wife’s heroic father!

So many examples of heroism here; the faces of the fathers heartbreaking and luminous. Thank you for this history.

Dear Arnold,

An astounding story! It seems as if the piano turned upside down just so the paper would be discovered. Could you tell from the scent of the cigarette paper which brand it was?

Do you think if you could have checked the DNA of this small piece of paper, you could have traced the cigarette holder?

Did Dodo saw it?

Love, Hava

Leave a Comment

*/