Perfect What?

January 3, 2011

My daughter, Natasha, told me recently about a gifted young boy she knows who has learned to read at an early age and already plays the piano with astonishing originality. As if to offer a final and irrefutable proof of the boy’s extraordinary musical talent, Natasha added one more thing. “You know, he’s got perfect pitch”. My wife, Dorothea, who was passing by at that moment and only half-listening to our conversation, demanded to know whom we were calling a perfect bitch.

While being a perfect bitch may be a subjective matter, having perfect pitch is easily defined. Perfect pitch, or absolute pitch as it is sometimes called, is the ability to name or reproduce a tone without reference to an external standard. All my life I have heard people speak in awed tones about musicians who have perfect pitch. But just how remarkable is it? After all, every one of us is capable of recognizing the individual voices of literally dozens of our friends and acquaintances on the telephone solely based on variations in pitch and sound quality.

I have perfect pitch. I either was born with it or acquired it when I began studying the violin at age six. At first, my father tuned my violin for me with a pitch pipe. He sounded the A, matched the open A string’s tone with it, and then tuned the other three strings, G, D, and E, by ear. I do not know whether dad had perfect pitch, but he certainly possessed good enough relative pitch to be able to discern perfect fifths, the intervals of the violins strings. At some point, I realized I could hear the A in my inner ear before I played it on the violin, thereby putting dad out of work. Once my parents realized that I had perfect pitch, they broadcast the news about their genius son around the neighborhood. I too was rather impressed with my gift at first and couldn’t resist showing off to friends by telling them that the beep-beep from the car horn they had just heard was an A and C above middle C, or that the back up sound of the garbage truck an E flat, and on and on. In music school, however, I began to realize that I was not that special after all. Many of my musician friends also had perfect pitch. Furthermore, absolute pitch is quite common among speakers of tonal languages such as Chinese or Vietnamese, which depend heavily on pitch variation across single words for meaning.

What good is perfect pitch for any of us who have it? True, if I am sight-reading a difficult contemporary score, for example, it is useful to be able to pick a note far removed in pitch from others out of thin air, but I feel rather guilty about it. My music teachers always emphasized the importance of what my father had—good relative pitch. Far better, they emphasized, for me to sense the relationship between a note and the one preceding it, to immediately hear the actual interval and quality of sound it makes whether, say, the grating tension of a minor second, the pleasing friendliness of a major third or major sixth, or the unsettling oddness of a major ninth—and then play accordingly.

Cursed or blessed, we perfect pitchers must live with this peculiar ability embedded in us, but often with unintended consequences. I once performed as soloist in a Bach Brandenburg Concerto with my violin and all other instruments tuned to the lower pitch of Bach’s time. Whatever note I played came out wrong according to my sense of perfect pitch. I found myself making uncharacteristic mistakes right and left. It took me hours to cast this so-called tone memory gift aside and rely with eventual success solely on relative pitch.

That’s at least a story with a happy ending. A cellist friend of mine with perfect pitch, Daniel Saidenberg, once bought a new car with a tape player that was a quarter tone off. Everything from Beethoven to the Beatles played ever so slightly flat. That relatively minimal pitch alteration slowly began to drive Danny crazy. Eventually, he tried to return the car but with no luck. The sales people thought they were dealing with a nut case.

The pianist Harold Bauer in his memoir, “His Book”, tells of hearing native Hawaiians play and sing their ancient songs but always in the same key. Bauer, who had perfect pitch, asked them to repeat one of the songs he had just heard, singing it purposely back to them at another pitch from the one they had used. The Hawaiians looked blank and said they did not know that song. Bauer insisted that they had sung it and repeated it again and again, each time starting on a different note. They disclaimed ever having heard it. Finally, Bauer sang it at the pitch they had used. Their faces brightened. Yes, that is our song, they said; and sang it to Bauer again. Pitch, according to Bauer, was to these people, the music itself.

My favorite perfect pitch story was told to me by a friend, the pianist Lincoln Mayorga. Lincoln went to Europe on a concert tour and woke up in the middle of the first night away from home jet lagged, and with not the faintest idea where he was. He had, however, one clue going for him—the hum of a refrigerator nearby in his hotel room. Appliances operate on 60 cycles in the Unites States and 50 cycles in Europe. A 60 Hz tone is between an A sharp and B two octaves below middle C, a 50 Hz tone is between a G and G sharp two octaves below middle C, something Lincoln was well aware of. Lincoln lay awake in his bed in the dark listening with his perfect pitch to the refrigerator’s hum and knew instantly that he was in Europe.

I’ve noticed that my sense of perfect pitch is beginning to waver occasionally with age. No longer can I pinpoint instantly and with absolute certainty that the winsome far-away sound of a train is a chord comprised of D, F, and B flat above middle C. Perhaps the chord is a half tone lower or higher. I’m just not sure. Several of my perfect pitch pals who are getting on in years have noticed the same thing. I’m not worried though. So what if the beep-beep of a car horn or the warning sound of a garbage truck backing up remains nameless. As long as I can retain my sense of relative pitch, I’ll be all right. But what if my relative pitch also begins to go? Now that would be a perfect bitch.

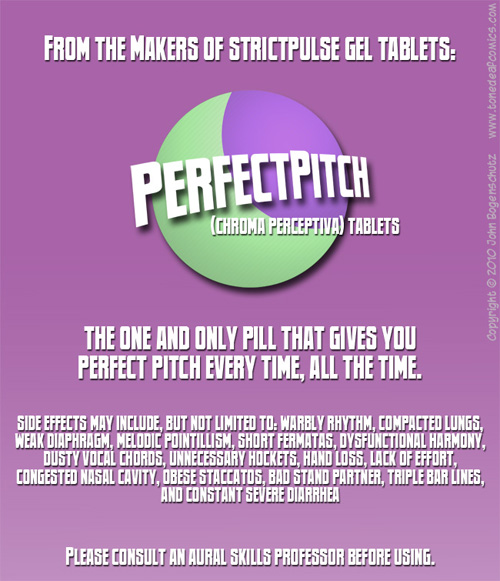

PerfectPitch Tablets by Tone Deaf Comics

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

Hi Arnold,

Thanks for another interesting piece.

It may interest you to know how perfect pitch has been used in biology. I heard a lecture in the ’60s from the then head of a major technology firm who was also an amateur ornithologist. His engineers built an ultra-high speed motion camera for him so that he could photograph & count the number of wing beats of a hovering hummingbird. He then told us that a simpler method was used by an Italian biologist with perfect pitch: he listened to the sound of a locust in flight & could immediately tell from its pitch what was the frequency of the wingbeats.

All the best,

Lee Rosner

I once accused a fellow Von Trapp child in our community production of The Sound of Music that she had called someone a bitch, when she in fact was complaining that they sang off-pitch. She was about 16, I was only 8, but I reduced her to tears after an hour of fruitless arguing and my stubborn insistence that she had made a swear.

I still feel bad about that.

I heard once of a Park Avenue Pitch. If so, how would it sound?

Dear Mr. Steinhardt,

We thought your “Perfect What?” essay was perfect. So did a number of my students (some with and some without perfect pitch).

But we look forward to and enjoy reading all your essays. So, please, keep ’em coming!

Thank you.

Rochelle Walton

Hello Mr. Steinhardt,

I always had issues with colleagues who tried to use their perfect pitch in quartet rehearsals. They would try to impose their idea of a “perfect” G-sharp, but of course as you know, a G-sharp is different depending on what role it’s playing at the time: a 3rd in an E chord, a tonic in a G# chord, or a leading tone in a melody.

Well, many years later I have heard from two different people that had perfect pitch and relied heavily on it, rather than learning their intervals. To their dismay, in their middle age, suddenly their pitch slipped a few steps! An A now sounds like an F, a C like an A-flat. And, since they had leaned on the perfect pitch, they now have trouble playing or even listening to music that they know, because it seems all wrong to them.

So I am glad to reinforce your advice to musicians not to rely on “perfect” pitch.

I have worked on and off for years for a conductor with perfect pitch. Believe me, Arnold, any connection between great musicianship and perfect pitch is truly a coincidence in your case.

Regarding perfect pitch, Arnold, in the second grade of elementary school I received straight A’s on my report card except for a C in music. Since I was rather precocious as a musician, my horrified Jewish mother who considered an A- unacceptable, confronted my unfortunate teacher and discovered that the pitch pipe that she used to tune the students for singing was off by a whole step. I had thought that being literal was commensurate with honesty, and had stood my ground.

And, alas, in recent years if the radio is soft and D and I are lulling ourselves to serenity and sombulance, I have to leave the room since the cacophony created by an aging auditory system is distorted enough to elicit giggles.

We really appreciate that our Friday night sightsinging group conductor Marge Naughton has this gift, but its often hell when we/she have to transpose.

Also had noted with friends, and as was explained clinically by Oliver Sacks {Musicophilia} that absolute pitch is statistically correlated with poor vision. He welcomes contacts from those concerned.

Is this something others find?

Making a paying career using perfect pitch

certainly seems a perfect bitch

When listening to the sounds

&

Their relations

Is your true

Vocation

Leave a Comment

*/