Sasha

December 1, 2021

As I passed the Curtis Institute of Music’s basement bulletin board, an announcement caught my eye:

Viola auditions will be held next month for the 1958 Pablo Casals Festival Orchestra. Please contact Alexander Schneider.

I was intrigued. The cellist Pablo Casals was a towering figure both in the musical world and because of his stand against fascism. As for Alexander Schneider, I had until recently known little about him except that he was second violinist of the renowned Budapest String Quartet. But at the end of the previous summer, two aspiring violinists, Jaime Laredo and I, had heard so much about the Marlboro Music Festival that we paid a visit just to see what it was like. While there, we attended a stunningly beautiful performance of Franz Schubert’s Octet for Winds and Strings. Alexander Schneider, the group’s first violin, was not only a formidable violinist and a highly individual musician, but in the way he assertively led the group and helped fashion the performance he seemed to be a veritable force of nature.

I was then a violin student at Curtis, but at some point during those school years I had fallen in love with the viola. Contemplating the audition announcement, I thought, “Why not audition for Schneider?” Several weeks later, two of us—I, the violist impersonator, and a fellow student, who was the real thing—took a bus to New York City, made our way to 23rd Street, and climbed four flights of stairs to Schneider’s apartment. The compact, middle-aged man who opened the door said with a distinctly Russian accent, “Vell, come in.”

Schneider’s apartment was spectacular in a chaotic kind of way. Oriental rugs were strewn here and there, photographs and paintings—some serious, some funny, some outrageous—covered most of the walls, and knickknacks of every size and description, perhaps collected from his travels, filled the room. It would have been nice to savor the exotic atmosphere that Schneider created, but he had already put viola orchestral parts on the music stand and pointed to my fellow student to begin.

Almost immediately unhappy with the student’s playing, Schneider tore into the poor young man. What I remember vividly was that Schneider told him he had the wrong teacher, the wrong education, and the wrong path to a career in music. There seemed to be no censoring mechanism embedded in Schneider’s psyche. What he felt, he blurted out. From my front-row seat on the couch, it was painful to watch.

Things went differently when it was my turn. Schneider kept on placing various viola music on the stand, all the while muttering words such as a“good”, “okay”, and “yes”. At audition’s end, Schneider offered me a position in the Casals Festival Orchestra.

On the bus trip back to school, I was over the moon with my good fortune, but sitting next to me was someone clearly devastated by Schneider’s comments. As happened surprisingly often for anyone, yours truly included, who crossed paths with this volatile man, Schneider’s condemnation turned out to be a blessing in disguise. His delivery may have been cruel, but he told the truth as he saw it. This young musician, recognizing even in his misery the great value of Schneider’s unvarnished appraisal, subsequently left his school and his teacher, and went on to have a highly successful career as a violist.

That April, sitting as last-chair violist in the Casals Festival Orchestra, I thought I had died and gone to heaven. Having just turned twenty-one and still in music school, I was playing in a phenomenal-sounding orchestra, conducted on occasion by none other than Pablo Casals himself. During the Festival, I heard memorable performances by, among others, Casals; the Budapest String Quartet; pianists Rudolf Serkin, Eugene Istomin, and Mieczyslaw Horszowski; and violinists Isaac Stern and Alexander Schneider, whom I soon discovered everyone called Sasha.

Even from the perspective of my youthful inexperience, it was clear that Sasha was more than a remarkable musician. He was the moving artistic force of the Festival, and the year before had taken over the prodigious work of managing the musical direction of the 1957 Casals Festival when Casals suffered a heart attack. Not only that, Sasha had earlier been instrumental in organizing the Prades Music Festival that had lured Casals out of retirement,

When the 1958 Casals Festival ended, I was happy that Sasha signed my program book: “Thank you and best wishes. Alexander Schneider.” But it was my hope that I could somehow keep in contact with this uncommon man who could provoke, stimulate, create, and inspire—sometimes all at the same time.

The opportunity arose that fall, when I won the Leventritt International Violin Competition. As I walked on stage for the competition’s first round, I could see Sasha and his cellist brother Mischa sitting among the judges, and I heard Sasha exclaim in a penetrating voice, “Isn’t he the one who played viola last summer in the Casals Festival Orchestra?”

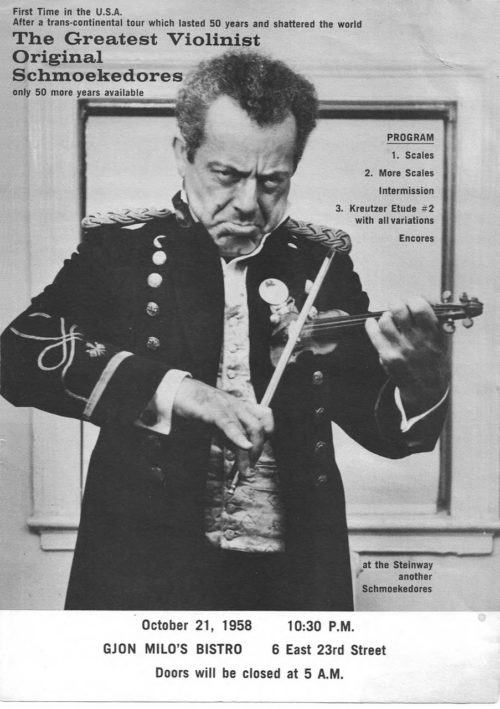

Perhaps because I was now on Sasha’s musical radar, an invitation to a party soon arrived from him in the mail. Accompanied by an outrageous photo of a funny-faced Sasha dressed in some kind of weird uniform and holding a miniature dance master’s violin and bow in his hands, the invitation announced:

As it turned out, this was a fiftieth-birthday party for Sasha, who was born in Vilna, Lithuania, on October 21, 1908. I eventually came to realize from many other splashy Sasha parties I attended over the years—his sixtieth and seventieth birthdays among them—that they were not only a celebration of Sasha’s own life but also a way for him to keep in touch with the many wonderful friendships he had cultivated through the years. Along with an impressive assortment of food and drink, Sasha also generously provided live music for us. A group of spectacular-sounding violists performed Bach’s Sixth Brandenburg Concerto, with Karen Tuttle and Sasha as exuberant soloists.

Clearly, my musical stock was on the rise with Sasha. As a matter of fact, since he heard me at the Leventritt Competition I had suddenly become one of the world’s great violinists, in his estimation. Consequently, Sasha arranged for me to play for Casals, who was visiting New York City. I should have known that danger lurked with the invitation. Casals thanked me politely after I played for him, but as soon as the door to his hotel room closed behind us, Sasha pounced. “I go to all the trouble to have you play for Casals, and what do you do? You play nicely. Nice is not enough for great music!” he yelled at me.

And of course, Sasha was right. Yes, I was young, I was inexperienced, and I was in awe of Casals, but my playing of a Bach solo sonata had been small, careful, and—that most dreaded word of all to describe a performance—nice. At that moment I had probably been unceremoniously stripped from Sasha’s list of the world’s great violinists, but his tirade was certainly beneficial shock therapy, whether I liked it or not.

When I saw Sasha heading toward me the next summer at Marlboro, my first of many there in the years to come, alarm bells went off. Was he going to chew me out all over again about my “nice“ playing for Casals? But Sasha either had forgiven me or forgotten the incident entirely. With hardly any greeting whatsoever, he pointed his finger at me and said, “You’re performing Bartok’s Second String Quartet this weekend.” I soon learned that he had also gone to Marlboro participants Leslie Malowany, violist, and Leslie Parnas, cellist, with the same news. None of us had ever played this treacherously challenging work, but Sasha had done so many times in the Budapest String Quartet. Sasha must have figured that, with Marlboro in need of repertoire to fill the early summer programs, he would simply by force of will and experience mold us innocents, in a mere matter of days, into musicians capable of giving a creditable performance of this string quartet masterpiece.

Rehearsals began the very next morning, with Sasha directing from the second violin seat. It soon began to feel, however, as if it wasn’t Sasha sitting in that chair but Béla Bartók himself. Sasha’s objective seemed to be not only the printed score but also the music’s very essence. He drove us to capture the first movement’s dreamy, impressionistic nature, the wild, primal fireworks of the second, and the eerie moonscape-like aura of the third and final movement. And here was a Sasha I’d not seen before. There were no outbursts telling us how bad we sounded. Instead, Sasha encouraged us to offer raw ideas of our own along with those of his born out of deep experience. The rehearsals under time pressure were scary but also thrilling, as the outlines of the quartet took shape. What normally might have taken at least a month’s work in bringing the quartet to performance level was compressed into five or six days. Nonetheless, Sasha must have thought somewhat highly of our progress, for on July 10 and 12, 1959, we performed Bartók’s Second String Quartet at Marlboro.

Among the many other participants inspired by Sasha at Marlboro during the following years were three friends of mine: violinist John Dalley, violist Michael Tree, and cellist David Soyer. When the four of us formed in 1964 as the Guarneri String Quartet, Sasha was there not only with a bottle of champagne and career advice, but also with a New York City debut on his New School concert series. That performance on April 11, 1965, was the beginning of a forty-five year career on the world’s concert stages.

In 1967, only three years after our Guarneri Quartet had formed,

the legendary Budapest String Quartet retired. It was assumed that each of the quartet’s members at that point in their lives would reduce their professional activities—but not Sasha. In addition to his work with the Budapest, he had already performed and recorded all of Bach’s Solo Violin Sonatas and Partitas; he had recorded many of his beloved Franz Joseph Haydn’s string quartets with his Schneider Quartet; and he had conducted much of the great orchestral repertoire throughout the world. Now entering his sixties, “Enough!,” you would think. But there seemed to be no end to Sasha’s energy and creativity. He became the artistic director of the Schneider Concerts at the New School in New York City from 1967 until his death, and in 1969, together with his manager, Frank Salomon, founded the New York String Orchestra, a year-end seminar and concert for young string players. In addition, Sasha never stopped performing and conducting throughout the world.

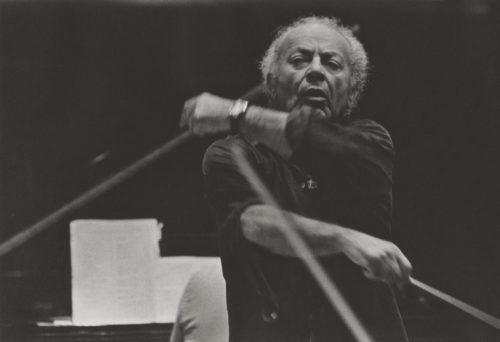

Sasha Schneider conducting in 1980. Photo © Dorothea von Haeften.

Our Guarneri Quartet continued to stay close with Sasha. We performed often on his concert series and participated in the early years of the New York String Orchestra Seminars. During Sasha’s by-now-famous parties, he would sometimes do hilarious impersonations of each member of our quartet as we walked on stage—John unceremoniously and swiftly moving to his chair, Michael looking like the Pope and solemnly holding his viola before him as if it were holy water, David carrying his cello at a rakish angle while leaning forward as if battling a strong wind, and I swaggering on stage with my chin jutting out comically.

Sasha and I continued our friendship as well. Occasionally I’d receive things from him in the mail—some funny, some bizarre, some of questionable appropriateness. Once, a large piece of cardboard arrived on which Sasha had pasted four images cut out of magazines—an angel, a priest, a boxer (James Cagney in a movie role), and an orthodox Jew. Above, he had written, “The Guarneri String Quartet.” Another was a simple postcard of a high-tech dairy farm with cows in their respective stanchions and a Japanese farmer dressed in an immaculate white uniform standing in front. Without greeting or signature, Sasha wrote, “The conductor Daniel Barenboim auditioning musicians for his orchestra.” And on the occasion of the Guarneri String Quartet’s twenty-fifth anniversary, during which a lot of fuss was made of this auspicious event, Sasha’s good wishes came in an envelope with a newspaper photo of four grim-looking South American generals in full uniform, and simply the words, “The Guarneri String Quartet celebrates its twenty-fifth anniversary.”

Even the greatest forces of nature must eventually run their course and fade, and so it finally was with Sasha. I visited him in late December 1992, just before leaving on one of the Guarneri’s annual European tours. Sasha looked pale and complained about a host of ailments that prevented him from being active. “What am I going to do,” he groused, “sit here all day and watch television?” I had never seen him like this before.

On February 2, 1993—the birthday of Jascha Heifetz, another famous violinist born in Vilna—Sasha passed away. But had Sasha really left us? Not in the hearts and minds of so many who crossed paths with him. Not for the aspiring young musicians who continue to perform on his New School concert series, and certainly not for those eager, gifted youngsters who flock from all over the world every December to the New York String Orchestra Seminar. It is still managed superbly by co-founder Frank Salomon, and, since Sasha’s passing, Jaime Laredo has become the Seminar’s inspirational conductor and artistic director—yes, the same Jaime who traveled with me to Marlboro well over sixty years ago when we heard Sasha for the first time.

I think of Sasha so often. I think of a dreamlike vacation spent in the Provence region of France one summer. Having heard that my wife Dorothea, our newborn daughter Natasha, and I were heading to Europe, Sasha generously offered us his house, a beautifully converted animal stable, replete with his beloved Deux Chevaux, a wine cellar, and the smell of lavender everywhere.

Then there was the time that pianist Cynthia Raim and I, upon finishing a rehearsal for an upcoming recital, found ourselves quite by accident in front of Sasha’s Manhattan house at 5 E. 20th Street. If he’s home, why not play part of the program for him, we thought. Sasha was home, listened to us play the Grieg C Minor Violin and Piano Sonata, and disliked our performance so much that he promptly threw us out of his house. Cynthia and I found ourselves once again in front of 5 E. 20th Street dumbfounded at what had just happened.

And I think of the time the violinist Isaac Stern and I happened to enter New York City’s Avery Fisher Hall at the very same moment, for a concert by the Brandenburg Ensemble with Sasha conducting. Isaac considered Sasha among his dearest friends, and I’ll let him have the last word here about one of the most remarkable and influential musicians of our time. As we headed for our seats, Isaac smiled at me knowingly and said, “Buckle your seat belts.”

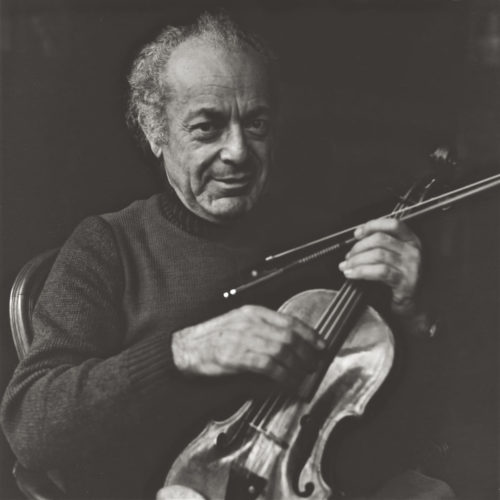

Sasha Schneider, August 8 1975. Photo © Dorothea von Haeften.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

Thank you so much for this! Even though I’d never heard Mr. Schneider play (or conduct) in person until I moved to back to NYC in 1977, his chamber music performances at the New School over the next several years were some of the peak musical experiences of my life. When he was playing first violin in a quartet or trio, he seemed always to be levitating slightly above his chair, so intense was his investment in each and every note!.

Oh Arnold, you capture the essence of Sasha. What a force of nature he was! No matter how outrageous he was, I always appreciated his insistence that every person in the orchestra give his all, all the time.

Your fiddle playing as well as your writing have the same wonderful effect on me: The notes and the words jump off the paper with spirit, energy and « don’t stop, I want to hear more! »

Many thanks for all your talents.

Wonderful!

Sometime in the middle ’40s when I was still in junior high, my Dad took me to a Budapest Qt. concert in Denver. We had seats upfront. During the concert, an argument broke out between the Schneider brothers. This, while Roismann continued to play with an unperturbed stone face. Kroyt also just played on without batting an eyelash. I can still picture this in my mind.

Fascinating and informative reminiscences. Thank you, Mr Steinhardt.

Did Sasha ever marry, have children? It’s hard to imagine ‘yes’ to either of those questions but I would like to know.

Thank you

What a lovely story, I wish I had known Sasha, but I did know Isaac Stern and read about how he got invited to the Prades Festival through Sasha. Wonderful memories!

Thank you. Beautiful tribute. He planted love of music deep in my heart

Who else would have invited Harold and his Music & Arts High School kids to perform Bach at Carnegie Hall?https://www.renaissancechorus.org/carnegie1955.jpg,https://www.renaissancechorus.org/renchoruspic.html

Is your son named for Sasha Schneider?

What a wonderful story about an extraordinary man. It must be wonderful to have all these memories stored in your head. Thank you for sharing them.

What a wonderful recollection of tales with Sasha. He was an indomitable force and one of the greatest blessings of my life! ??

What a wonderful Srawberry Story! Not surprised. He always connected. I was not in his orbit but he would greet me with entusiasm either in Marlboro or NYC. I recall that Debby spent part of the summer with him in his Provence home.

I’ll call you soon snd catch up.

Love to Dorothea and you. Happy holidays, as they say.

John

Sasha was a force of nature. A one-man hurricane. I miss him and his fiery commitment to music making on the highest level.

“Ya come, articulate!”

While I’m not a musician, I totally relate to and love your Sasha story! Having attended the University at Buffalo 1962-66, where I also attended the Budapest String Quartet’s annual Beethoven cycle, I became familiar with the incomparable Sasha Schneider. As I worked in the music dept library I was sometimes assigned to open the door for the Quartet members to enter the stage and thereby had the chance to see them at close hand. Later as Box Office Mgr at the Met Museum’s Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium and a Frank Salomon Associate, I too saw those silly birthday party invitations and attended several of the Unforgettable Sasha milestone celebrations! Thanks so much sharing your delightful memories of this amazing musical character, teacher, mentor, and unique artist we were privileged to know!

Leave a Comment

*/