Practice? MMMaybe Not

September 2, 2020

If I don’t practice for one day, I know it;

two days, the critics know it;

three days, the public knows it.—Jascha Heifetz;

But Mr. Heifetz, what about four days, or four weeks, or, gasp, even longer?

During a busy performing schedule, I would sometimes take a day off here and there; and in the summer, one or even two weeks. I felt that it was wise to give both my body and my mind an occasional vacation from the instrument. Of course, Heifetz was right in the sense that performing on the heels of those time offs would be tantamount to professional malpractice.

The longest I ever parted company with my violin, however, was in an unplanned, unwanted, but unfortunately, unavoidable situation. Fresh out of music school and in disgustingly good health, I was about to be drafted for two years of active duty in the United States Army. This was not good news, for I had just been offered the assistant concertmaster position in the world renowned Cleveland Orchestra- a plum job at any time but especially for me as a twenty-one year old just starting my life as a professional musician. There was a solution to the problem, thankfully. If I joined the Ohio National Guard, only six months of active duty was required, and I would then be able to accept the coveted assistant concertmaster position. There was no question in my mind. I agreed to become a soldier.

Active duty in the Guard was divided into three two month periods: basic training, advanced basic training, and finally a cushy job playing glockenspiel and bass drum in the 122nd army band. In those first two months, I had to learn how to shoot a rifle, crawl under barbed wire with live machine gun bullets flying overhead, and march with full gear in the insufferable Fort Knox heat. Oh, and one more thing: I was not allowed to bring my violin to camp for the duration of basic training.

Sergeant Jones was in charge of recruits. He was tough but fair-minded as we went through our daily physical training. “Hit the ground and do twenty-five pushups”, he would bark, and then walk slowly past each of us in order to see how we flabby, out of condition weaklings were doing. Suddenly, I felt a boot on my backside. “Steinhardt”, he hollered, “your butt is fanning the air. Twenty-five more pushups for you”. Jones was right, I had to grudgingly admit. My butt was indeed fanning the air. Dutifully, I did twenty-five more in the hot, humid sun.

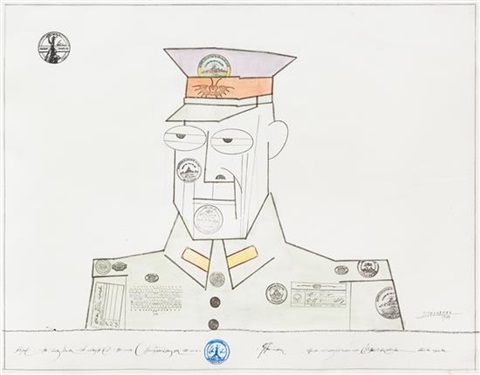

Saul Steinberg

For the first few days, I didn’t miss the violin. Up at dawn, pushups, pull ups, scaling walls, learning how to take apart and put back together an M1 rifle, and the dreaded marches up aptly named Misery Hill was a full time occupation. But as the days went by and my physical condition improved- that is to say, my butt no longer fanned the air while doing pushups- I began to long not only for the silvery sound that could waft out of the violin’s F holes, but also the tactile sense of running my fingers up and down the instrument’s fingerboard and the reassuring feel of the bow stroking each of the instrument’s four strings. After all, I had been playing the violin almost every day since I was six years old.

And I missed music terribly, whether playing or listening to it. Occasionally, I would hear snippets of country western or jazz coming out of a distant radio, but the army existence was a wasteland in terms of classical music. Once, while suffering from a rash that never seemed to go away, I was sent to the base hospital. As I sat waiting for medical attention, sounds of the Beethoven Violin Concerto drifted out of one of the nearby rooms. Tears of gratitude welled up in my eyes. For that brief moment, the gruesome articles of war I was being trained in vanished, and Beethoven’s music comforted me in a way I’m at a loss to describe.

When the two months of basic training were almost over, I eagerly contacted the friend of mine in Cleveland whom I had asked to send a violin to me. Suspecting that the rough and tumble soldier life might not be ideal for the exquisite sounding and highly valuable nineteenth century Italian violin I owned and performed on, the cheapest fiddle I could get my hands on took its place. Almost as an after thought, I had it insured for one-thousand dollars, a pittance in comparison to the value of any self-respecting violin.

One early morning, I suddenly heard my name blaring out of our barrack loudspeaker. “Steinhardt, you’re wanted on the double at the base post office”. When I arrived there, Sergeant Jones was waiting for me. “Steinhardt”, he growled, “what the fuck is in that box that’s worth a thousand dollars”?

Here, I must momentarily depart from the story to explain a remarkable but well-known aspect of army life. Speaking without using the F word in almost every sentence, is just not done. At daybreak you might hear, “What’s the fucking weather like today? ”, or at dinner, “Pass the fucking peas”.

So, Sergeant Jones’ choice of words in asking what was in the box valued at one-thousand dollars was unremarkable, although it certainly deserved an answer.

“There’s a violin in the box, Sergeant”.

“A fucking violin worth a thousand buckeroos? Open the damn thing, Steinhardt”.

When I had successfully dismantled the cardboard box and opened the violin case, Sergeant Jones approached the violin resting peacefully in its quarters with a combination of awe and suspicion.

“You play that thing?”

“Yes, Sergeant”.

“You any good?”

“Well, I’m a professional musician.

With that, Sergeant Jones’ demeanor changed dramatically. He sat down at his desk, put his booted legs on its top, and said with a wicked grin plastered all over his face:

“Steinhardt, you are not getting out of this place with your fucking violin unless you play Flight of the Bumblebee for me”.

Although I was impressed that Jones knew of this virtuoso encore piece lifted from Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera The Tale of Tzar Saltan, there wasn’t the remotest chance I could play it. I’d never studied Flight of the Bumblebee, and even in top form, it would have taken me innumerable hours to master its whirlwind nature. When I explained this to Sergeant Jones, he remained silent for a moment, and I began to fear that he would simply say: No Flight of the Bumblebee, no violin. But Jones was not finished.

“OK, Steinhardt. Forget Flight of the Bumblebee. Play Fascination for me, instead”.

The song, Fascination, was composed in 1904, but the lilting waltz had staying power. Nat King Cole recorded it (with a gorgeous trombone solo in the middle) and it also had an appearance in the 1957 film, Love in the Afternoon, starring Audrey Hepburn, Gary Cooper, and Maurice Chevalier. This was now 1960. Sergeant Jones, obviously, knew the song, and so did I. If you had asked, I would have been able to sing it badly with my croaky voice, but after two months AWOL from the fiddle, the question was, could I play it.

I picked up the violin and bow, two old but temporarily estranged friends, and drew the bow across the strings in order to tune the instrument. This gesture, done thousands of times throughout the course of my life, felt so familiar, so normal, that it gave me the courage to simply dive in and begin Fascination. Lo and behold, my fingers obeyed my commands and the right notes began to emerge. Deep neural pathways between hands and brain set in motion at childhood must have been at work. When I came to the end of the song, Jascha Heifetz’s admonition took center stage. The critics would definitely have known I hadn’t practiced and so would the public, but in this case, not Sergeant Jones. He jumped up from his chair and practically shouted at me, “Steinhardt, you sure can play that fuckin’ fiddle”.

That night, I played the violin next to my cot in our barrack. In a matter of seconds, I was surrounded by many of the guys with whom I had spent the last two months in training. They listened to me with curiosity and interest, and they asked questions: Where’d you learn to play? Do you earn a living from this? Do you make a lot of money? Where are you from? What’s your religion?

They appeared to come from all walks of life, but none of them at least in this group had ever heard a single note of classical music. Nonetheless, the guys accepted me and my Bach, my Paganini, and even my boring scales, graciously. For the next two months of advanced basic training, and then for the last two months along side of my performances on glockenspiel and bass drum in the 122nd Army Band, I practiced.

By the time I finally sat down in my chair as assistant concertmaster of the Cleveland Orchestra and waited for its conductor George Szell to mount the podium, all that practicing compliments of Uncle Sam seemed to have paid off. I was once again in solid form as a violinist.

But what did I actually learn from those six months in the army? Certainly, not that I would have made a very good soldier. I hated cultivating how best to kill my fellow human beings. There were two moments, however, that stand out in my mind among all the implements of war we recruits were constantly confronted with. I will never forget sitting in the hospital as strains of the Beethoven Violin Concerto wafted out of a nearby room. Those sweet sounds reaffirmed just how profound music’s hold on me was. Then there was strict but fair minded drill Sergeant Jones who could easily have let me and my violin escape without musical payment, but didn’t.

It has been sixty years since I played Fascination for you, Sergeant.

Let me play it for you once again.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

Thank you Maestro! I shared your story with many friends this morning…both amateur and professional musicians, and even more numerous: enthusiastic audience members. I tremble to imagine where I would be without the comfort of music in my life. I have played the cello for over 50 years. For the past 25 years, I have been in a string quartet. Our Covid-19 enforced break from March until the end of July was the longest we have ever been away from each other. For a few more weeks, we are enjoying our roughshod versions of Haydn and Schubert, playing outdoors. I hope we can find someplace drier and warm to play through the upcoming winter here in the Pacific Northwest.

Thank you for sharing your stories and your music with us. It is wonderful to hear your lovely, lyrical playing. I studied with you at University of Maryland in the 90’s. You’ve made a huge impact on my playing and my life. So wonderful to reconnect with you now through this blog. Keep writing and keep playing for us, please. Such an inspiration.

Sincerely, Wendy Harton Benner

As usual, a wonderful story. Fascinating.

I’ll contact you to say hi.

Best, John

Beautiful, heart warming, sincerest thanks.

As always a very touching story. And you sure can play that fiddle!

What a delightful story, thank you.

Thanks so much for this story, and the “Fascination” performance! I appreciate the time you take to publish these stories and enjoy each and every one of them immensely.

All the best!

My mother (who passed in 2016) was a country music fan, but Fascination was her absolute favorite song. She used to hum it around the house, and I can’t hear it without remembering her. So thank you, Mr. Steinhardt, and Sergeant Jones!

I am a huge admirer of your playing, but also your writing.I heard the Guarneri String Quartet in Sedona many years ago (I live in nearby Prescott),and cherish several recordings. “Indivisible by Four” is one of my favorite books. I I grew up in San Francisco, with Pierre Monteux conducting and Rudolf Ganz’s delightful Children’s concerts.

Thanks for this story. I realize that long before listening to you on recordings of the Guarneri, I heard you in Severance Hall; I grew up in Cleveland and in high school in the late 50s-early 60s, I went to the orchestra whenever my parents would give me one of their seats. I especially remember two concerts: Beethoven 7, and Britten’s War Requiem.

Lovely. Thank you. Now the pushups…?

Thank you for the music.

More would be good, for all . . .

What a heart warming story. Your playing brought a tear to my eye. Thanks for sharing this story.

I love these stories. Thanks!

Thanks for this lovely story (and performance). Glad to see you looking so well.

Thank you for the performance, Maestro!! After I listened to you I looked at your chickens, LOL! Interesting story for this time in our lives of chaotic violence. It’s scary out there! Where will all the musicians go? Orchestras? IDK. Very sad times for me, perhaps similar to World War 2 when my dad, a professional “great” oboist” fought the Germans and won!

. I wonder how long Dad didn’t have his oboe. God Bless Him and God Bless Biden!

Thank you for sharing!!

Be well!

I am a life-time amateur chamber music player and have attended many or your concerts here in Los Angeles. It was always a thrill to hear your quartet (and read your 2 books) Now, though I can no longer play as I am older than you and quite deaf, I really enljloy your stories. Please tell thelm more often!

Thank you so much for sharing this story. ? I just loved it. I’m so glad you survived intact. Thank you for all the beautiful music you have shared including Fascination. ?

Mr. Steinhardt,

The portion of the story when you randomly heard the Beethoven concerto in the army hospital was NOT read without moistening of the eyes. My daughter just did some time in AF Basic Military Training, because she enlisted in the Illinois Air National Guard to help pay for her college tuition. I’m a professional violist, so I relate to your story doubly to your story.

As always, your story brought joy, enjoyment, as well as appreciation for all things of which you wrote.

Lastly, I’ve always thought of you as a charismatic person, and this video proves that it hasn’t changed! You will always have fans and admirers for all the great work you’ve done over your career; not only of the legacy of the Guarneri, but even with your solo career, and I have some recordings to prove it!

Thanks again, and KEEP ‘EM COMING!

Peter

M’Gosh! I had the same National Guard/6-month training (Ft. Jackson SC). I, too craved hearing classical music, but didn’t have the Beethoven experience you did. My earworms did produce movements from Handel’s Messiah, which helped during KP duty. The “f” word is certainly a cut below the “f” hole.

Dear Mr. Steinhardt,

thank you for yet another wonderful story. Your articles are always a source of inspiration. Your blog has been the motivation for me to start my own blog (www.violinmatters.com) where I write about violin teaching and learning.

Leave a Comment

*/