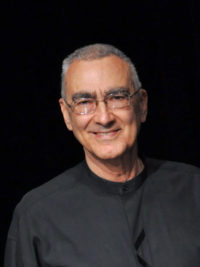

Michael

August 8, 2018

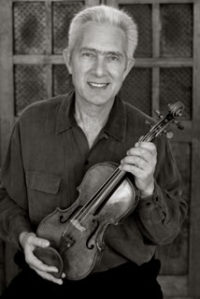

In all the forty-five years that our Guarneri String Quartet performed in public, and during the nine years since we retired, I don’t believe I’ve dreamt of the quartet more than a handful of times. This might seem odd to string quartet aficionados who know how much must go into a performance: practice and more practice, discussion and disagreements, endless and often exhausting travel, and, finally the high bar we set for ourselves in performance itself. Lots to dream about, wouldn’t you think?

I wonder myself why I haven’t dreamt more often about our quartet. Perhaps it has to do with the nature of who the members of our group are and how we operate with one another. We are a rowdy bunch—like four opinionated brothers you might say—who, while maintaining a certain amount of respect and politeness in rehearsal, have no qualms about truth telling.

A most unprofessional explanation of my Guarneri-less sleep might be that our openness and frank criticism during rehearsals—for the good of the performance rather than to squabble with each other on a personal level—meant that each of us walked out of rehearsals relatively unencumbered by smoldering resentments or unresolved issues. And therefore presumably nothing of substance to dream about.

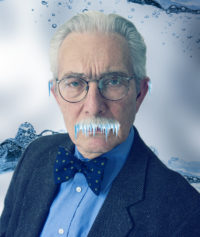

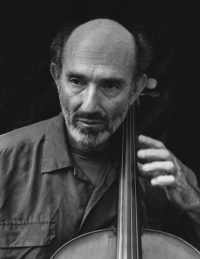

Several weeks ago, however, I did dream about the quartet. I awoke both surprised the dream had happened and amused at its utterly mundane nature. It involved a single bar of music during rehearsal in which violist Michael Tree and I shared a passage with exactly the same notes and rhythms. As we played, both Michael and I made a slight swell in volume as indicated, but our swells unfortunately peaked at different times. This was the most minor of details that would have to be sorted out. Should I do it Michael’s way, or would he agree to my way, I asked. An impish smile crossed Michael’s face as he began to respond, but just at that moment I awoke.

Why a Guarneri Quartet dream and why about Michael, I wondered as I sat up in bed. And then as the fog of sleep lifted, the answer came rushing at me unavoidably. Several weeks earlier, on March 30th, Michael had passed away.

After the quartet retired in 2009, Michael and I remained fast friends and occasionally performed together at music festivals. Now and then I would visit with him in the very last years when his health began to fail. As chance would have it, my last visit was the day before Michael died. His wife, Jani, and I sat across from Michael as he, no longer conscious, lay in bed. I held his hand and spoke a few words to him in the hope that he heard me on some level, and then Jani and I told stories about Michael—his artistry, his humor, his importance to our musical community.

Since Michael passed away, I’ve thought a lot about our 64-year-old friendship, but there are so many moving parts to it. In 1954, as a first- year student at the Curtis Institute of Music, I heard Michael before I actually met him. He gave a recital at Curtis Hall as an already superb violinist, but what struck me was the compelling nature of Michael’s music making—the sense of rubato and nuance the way he shaped a phrase. Here was a big musical personality.

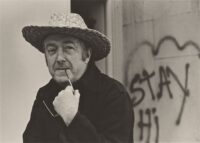

Michael and I soon became good friends. He was funny, quirky, boisterous, a great storyteller, and highly opinionated, especially about music. For me, seventeen years old, Michael was a most intriguing fellow. As he was the older, more experienced boy, I began to follow his lead in all kinds of ways. Michael wore tweed jackets. I bought a tweed jacket. Michael had a pipe collection and smoked Balkan Sobranie tobacco, so I did the same. We were two Jews, one from LA and one from Maplewood, New Jersey, both trying to pass ourselves off as English gentlemen.

During our years together at school—during one of which we roomed together—Michael and I played hundreds of hours of gin rummy, went to innumerable movies, ate endless meals with our student friends in China Town while fighting with chop sticks for the best pieces of sweet and sour shrimp, and played incessant practical jokes, one of which backfired when I enacted a scene from the French horror film, Diabolique. Unfortunately, it scared Michael half to death and almost got me thrown out of school.

All of that, of course, was merely a way of letting off steam while we tackled the serious business of becoming musicians. But there was more. At that time, many violinists in the school, and that included Michael and me, hoped to be the next ravishingly brilliant violin soloist. As for chamber music, the exalted repertoire was our education, our joy, and our inspiration. Michael was one of many who studied chamber music as part of the school curriculum and often enjoyed playing string quartets late into the night for sheer pleasure, but for a career? Chamber music and more specifically string quartets might be a cherished sideline, but surely they were hardly a way to make a living.

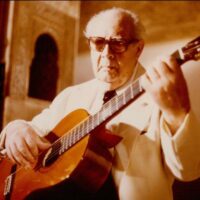

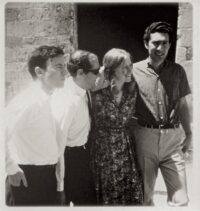

That was about to change with the ever-increasing presence of the Marlboro Music Festival. Here were great soloists of the time such as Rudolf Serkin, Marcel Moyse, Alexander Schneider, and Pablo Casals performing chamber music to large and enthusiastic audiences. Marlboro proved the lie that chamber musicians were merely failed soloists. The festival opened up a new world of possibilities by blurring those lines between soloist and chamber musician.

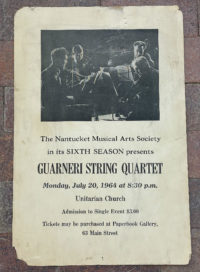

Several of us from Curtis, including Michael and John Dalley, violinist, found Marlboro irresistible. We spent summer after summer studying and performing the hallowed chamber music repertoire. And gradually but somehow inevitably, our priorities began to evolve. Michael and I first began to talk with each other about forming a string quartet, then we talked with John Dalley, and finally with cellist David Soyer.

When the decision to form a quartet at the end of summer 1963 took place, David would obviously be the cellist, but who would the violist be? The three violinists, John, Michael, and I had all loved playing viola, but before any discussion could take place, Michael firmly claimed the position for himself. John and I put up no argument, for we had often heard Michael performing as violist. Violinists who pick up a viola often cannot avoid still sounding like violinists. Their vibrato is too fast, they tend to skim the strings in the violin manner, whereas the viola demands a slower bow speed and a different bow pressure in order to plumb the dark, rich, and seductive sound the instrument is capable of. But Michael was a natural, and he must have sensed at that moment that his future lay with this larger instrument.

One of our very first performances as a string quartet in 1964 at Marlboro was of Paul Hindemith’s Quartet Opus 22. Frank Salomon, co-administrator of the Marlboro Music Festival, played a recording of the performance for me not long ago. I had no idea such a recording existed and I was nervous to hear what easily could have been a tentative performance by four guys just starting out on their quartet adventure. Hindemith, a violist himself, had given ample and challenging solos for the instrument. The four of us played well enough, but Michael sounded phenomenal as a masterful instrumentalist, as a team player, and as a fully formed and charismatic musician. All those jokes about poor violists were rendered obsolete at that moment.

For better or worse, rather than blending in a unified sound and interpretation at all times, we chose to maintain our individual personalities whenever possible. This was clearly evident in Michael’s swashbuckling opening viola solo of Smetana’s From My Life Quartet. No one else could have sounded like Michael—unabashedly open-hearted, daring to impatiently move forward with the music’s increasing intensity, and all done with immaculate precision.

And then, the Guarneri String Quartet went on to perform on the world’s concert stages for the next forty-five years with only one change of membership when cellist David Soyer retired and Peter Wiley took his place. How did that happen? The simple answer is that we played well and people kept on hiring us. But the concert field has other such successful groups that have changed members at will or collapsed entirely. Our luck was that we had a workable and mostly enjoyable chemistry. And Michael was an integral part of that: full of useful ideas, able to take criticism well, almost never moody, and with an over the top sense of humor.

String quartets have often invited me to perform with them as guest violist. This has put me in the unique position of seeing how they operate first hand, and how every one of them seems to have a distinct personality. One group was overly polite and could hardly muster criticism. Another was serious, sharply critical, and uncomfortably tense. A third talked more than it played during rehearsals. The Guarneris? We could be intense, argumentative, sometimes immersed in seemingly insignificant details, but our overarching mood was open, good-natured, and often raucously funny.

Michael was the ringleader when it came to jokes and stories. Often he would relate an event that both of us had witnessed but that I hardly recognized in his retelling. Michael would get carried away as he turned a simple story into a full-blown melodrama full of details that I had hardly been even aware of. Knowing Michael full well, the rest of us could not help laughing even as we rolled our eyes in disbelief.

When it came to concerts, however, Michael was utterly serious. After performances, he often made notes of what he felt had been lacking. At the next performance of the work, whether it was the next night or three months away, Michael would bring his comments to us beforehand. This was laudable and also extremely useful.

That is, except once in Eindhoven, Holland.

Michael came to each of our dressing rooms before the concert to ask permission for him to begin the last movement Fugue of Beethoven’s Opus 59#3 Quartet a little more slowly. He felt that we were playing the Fugue at such a clip that many details were falling by the wayside. We all agreed. Why not take a tad off the tempo of this wildly brilliant movement for clarity’s sake. But Michael miscalculated as he began the Fugue. With the best of intentions, his tempo sounded as if he was practicing in slow motion. The rest of us looked at each other in astonishment. After practicing for months to play the almost impossibly fast tempo that Beethoven indicated, we somehow managed to get through this waterlogged rendition.

In the wings immediately after, Michael raised his voice to carry over the applause that was still continuing. “I’m sorry. I’m sorry,” he said, looking sheepish. “I miscalculated.” “Never mind” answered Dave. “We are going out there and playing the movement again at the RIGHT tempo this time.” “Alright. Alright,” said Michael with a somewhat crazed look on his face. As he put bow to string, I was entirely unprepared for the fastest tempo I had ever heard. Again, the rest of us looked at each other in disbelief. How on earth were we going to play a tempo that would have astonished even the great Beethoven. The Eindhoven audience was given the once in a lifetime experience of hearing both the impossibly slowest performance of Beethoven’s fugue ever, followed by the impossibly fastest rendition ever.

Lucky them.

What do quartet members do on tour after they have traveled, checked into the hotel, practiced individually and rehearsed? In their free time they might read a book, watch TV, or go for a walk. But for Michael and me it was tennis. If possible, we would arrange ahead of time for a court and even players for doubles drawn usually from the chamber music board. Tennis rackets were usually stored with our instruments in the plane’s overhead racks. Were we accomplished players? Not particularly, but it didn’t really matter. We loved the game, it was good, healthy exercise, and Michael and I always pushed ourselves to the limit in order to win.

Ironic that in performance only a few hours later. Michael and I were often playing phrases together that required consideration, thoughtfulness, and deep cooperation rather the competitiveness needed as we bashed the tennis ball back and forth. In the second theme of the first movement of Maurice Ravel’s String Quartet in F Major, Michael and I play in octaves this achingly tender melody, making a slight nuance together as the harmony changes, and finally lingering oh-so-softly at the end of the next bar—an “ooooh” moment for the audience if we do it well. This was music making, of course, but you might also call it a very special kind of friendship that existed between Michael and me for those fleeting moments of the second theme.

The Guarneri quartet acquired a curious rehearsal technique early on, one that happened without planning or discussion but that somehow stuck. We never complimented each other. It was assumed that each of us was expected to play well and that comments were only for constructive criticism. For example, if Michael had ever said to me, “Oh Arnold, I just loved the way you played that phrase,” my first thought would have been that I was about to be fired.

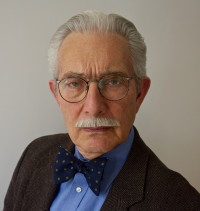

But the Guarneri Quartet retired almost ten years ago and somehow that releases me to say something to you, Michael, that I would not have dared to say in all those forty-five quartet years together.

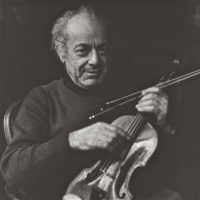

I loved your playing, Michael. I loved the freedom, the expressiveness and the very personal character of it. I loved the melancholy in it and that gorgeous dark chocolate sound you were able to muster at just the right moments. That won’t be forgotten by all of us who had the privilege of hearing you, working with you, and by those fortunate students who studied with you.

We thank you, Michael.

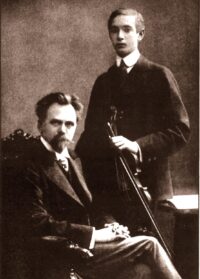

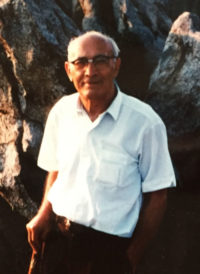

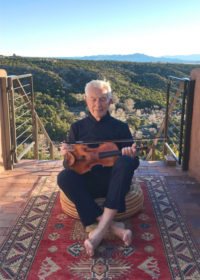

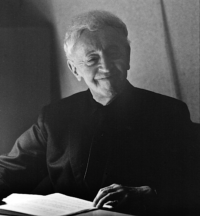

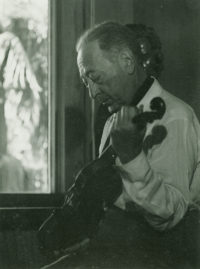

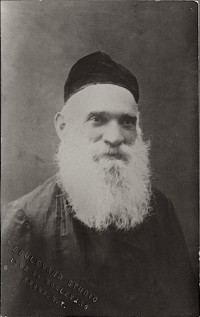

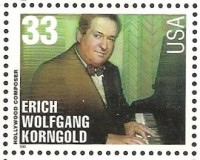

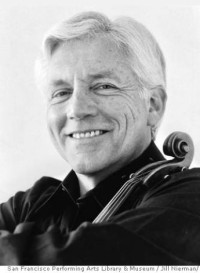

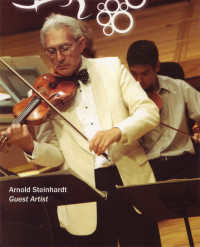

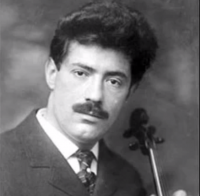

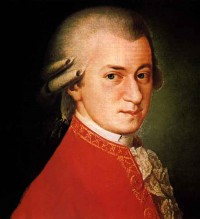

Michael Tree, 1974. Photo © Dorothea von Haeften.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

3 Trackbacks/Pingbacks

Comments

This is such a moving tribute to your quartet mate and friend. I was fortunate enough to study violin while in high school with Michael’s father, Samuel Applebaum. He was a kind, generous, and inspiring man. He set me firmly on the path to my own musical career in the gentlest way possible. Michael’s mother was warm and caring as well, and that light in Michael’s eyes, I always thought, was inherited from both his parents. Thank you for this, and for writing such a heartfelt and informative blog in general.

That was beautiful. Thank you for sharing.

so touching

Beautifully written, Mr. Steinhardt!

After hearing news of his death, I played the last movement of Razumovsky no. 3 quartet. That same anecdote in your book never failed to illicit a chuckle for me — how the first rendition in that concert was like entering the hot tub with a glass of wine in one hand, while the encore was a fleeting frenzy.

I’m sorry that I never heard the quartet in person. He will be missed.

Arnold – You always manage to do it but this time was certainly different and must have been very difficult for you to write. As you know,I have known the Quartet since it was first formed in Marlboro in 1964 and this brought back a flood of memories but such fresh insight as well and I am really grateful. I, like everyone, loved Michael and thank you for letting me peer on the inside a bit of your incredible relationship.

What a beautiful homage! The man was and will always be a legend. It was an honor to work with him. Thank goodness for all those great recordings we have

So beautifully and truthfully written, Arnold. Brings back memories.

On the tennis court, Michael was a fierce competitor, never wanting to lose, driving me crazy with his dinky shots and placements.

I am distressed to hear the Michael Tree has passed away. I have followed the Quartet from the early concerts at Virginia commonwealth University to New York to the near-final concert in Kansas City. And a lot in between. Somehow, I feel that I know all the members personally, and so I do feel Michael’s loss with real sadness.

Lovely story… thank you

Thank you for sharing your memories of Michael Tree and the experiences you shared in the Guarneri Quartet. The music of your collaboration resonates verbally in your loving words- –X4!

I absolutely loved this tribute to Michael, a violist that I and all my violist friends have held in high regard, especially as we were coming up through the ranks. I remember hearing the Guarneri at Stanford, where I studied with Bernie Zaslav. Now as a Chicago-based violist, I am so incredibly grateful to the rich heritage of quartet violists who have been a guiding light on what it means to be a great chamber musician and champion of our beautiful instrument. Thank you. thank you, Arnold for your elegant and eloquent words!! I find your literary style as engaging as your playing and I so appreciate the Guarneri’s dedication, artistry and sense of humor.

jhpchun@gmail.com

I’m a violist, and virtually life-long Guarneri fan. I started to play the viola two years after starting to play the violin, because I was seduced by the tone of Pinchas Zukerman. Some years later, I found a rather rare record of Zukerman playing trios with his then-wife Eugenia, and of all people, Michael Tree. That is the only time I listened to Zukerman play (violin, naturally, since Mr. Tree was on…) ANYTHING with other people and my ears did not naturally get drawn to his inimitable and characteristic tone, because I was drawn this time instead to Mr. Tree’s tone, which I consider to be the most gorgeous EVER to be heard. This is so much so that when I had the good fortune to play with Peter Wiley at a festival in Korea, just before the first rehearsal started I got REALLY intimidated, realizing that here was a man who sat right next to the most gorgeous viola sound ever, for some years. That really was my thought as we started to rehearse. I began to feel I was torturing the poor man with my own much poorer tone… I treasure the memory of having heard you at Jordan Hall in Boston, and in a much poorer hall in Lawrence, KS, and of course all the treasures you all left for the world through your incredible records, some of which are finest ever.

Thanks for sharing these touching and beautiful memories of Mr. Tree.

Dear Arnold,I sit here in tears reading your tribute to Michael. Adrian also respected and loved him. They performed Harold in Italy together and it remained a fond memory. We too shared happy times with Michael and Jani. I mourn his passing away. Thank you for writing so memorably about Michael. Warm regards to you and yours. Sheila Sunshine

Beautiful tribute. Thank you, Mr. Steinhardt.

A wonderful, heartfelt tribute. Thank you.

I love your stories and the way you write them.

I heard the Guarneri quartet in Holland more than 20 yrs ago and since then I’m one of your greatest admirers!! Your way of expressing each individuality within the unity of the quartet is quite unique!!

What a lovely and heart warming story! I was fortunate to have heard you both up

at Marlboro in 1979, and on many occasions thereafter! Thanks for sharing these

reminiscentes with us.

Oh, Arnold! What a wonderful touching tribute. That last paragraph is etched in my memory for good!

Thank you very much Mister Steinhardt for such a touching and heartfelt tribute to such a close friend and colleague of yours. We cherish your music, you gratify us with a beautiful blog (I am about to read INDIVISIBLE BY FOUR I have by my side). Art and Class always lies in the soul of artists, with or without their instruments. Best regards, Pierre Filmon

Where can I write my comment for this most moving remembrance? Hava

I complement you both on your beautiful writing and your out of this world relationship with Michael Tree.

Love and respect,

Gene

Thank you thank you thank you.

Oh Arnold! You never fail to take me with into adventures and insights and here, into such a tender reflection on your friend and fellow quartetnik. Thanks for all the stories you share and for that musician’s heart that sings through all your work. Love Sonya’s

Thank you, Arnold, for this wonderful tribute. I am fortunate to have known Michael, indeed to have known all of you in the Guarneri Quartet. Michael was a rare musician, teacher and man – we are all the better for having known him.

As Miriam Makeba sang, “Love has a bright strawberry taste.” and as Bruce Adolphe said, “Chamber music is the music of friends.” This story was a beautiful tribute to both. Thank you.

Mr. Steinhardt–I love you so much. Rosie H., vla

Scott, thank you ever so for you post.Much thanks again.

In my years in public radio, I often played recordings of the Guarneri Quartet, and rattled off your names in the “back announce.” So what a great pleasure to read your tribute to Michael Tree and bringing out his personality beyond the recordings. Your writing is a beautiful tribute. Thank you.

Wonderful words. I hope you write more. You really should.

I ran into you four backstage on a couple of occasions. The first time in the 90s you were being held hostage in Melbourne for some ‘T-shirt photo op’, and the photographer was late… Michael was quite funny about it despite the absurdity of the situation. Once backstage in Köln when I asked Michael about some fingering solution for a late Beethoven qt to which of course he replied with one eyebrow raised: “depends”. (The correct answer to what was probably a silly question)

As a young student quartet in Germany we used to sit there and play his 59.3 intro again and again. We would just just laugh at how good it was. I don’t know how he did it. So clean, so fast. My friends who studied with him were all so so sad when he died. A couple of them, like you got to go and see him near the end when he seemed to have a sharp memory for certain incidents.

Thank you for this touching tribute. I have been a fan of the Guarneri Quartet since the ‘80s and had several opportunities to hear your live performances. Michael was truly one of a kind and just a terrific violist and musician. As a violist myself, I often drew inspiration from his style, boldness, virtuosity and tone. He and the quartet are one of the main reasons I fell in love with chamber music in the first place. And, you have a gift for writing, also. All the best and thank you again.

Dear Mr. Steinhardt,

I am a violinist from Brazil, currently based in Rio de Janeiro. I am currently member of a full time string quartet. Since I am no longer in school and I was looking for guidance and advice, I have just concluded to read your book “Indivisible by four”. Thank you so much for sharing so many different aspects of what is to be part of an ensemble. Everything from the musical side of things to the business side of it, I was touched by your way of presenting the ideas. I could perceive that you and you quartet fellows had a very balanced relationship. Human, with honesty and truthfulness to it! I never met Mr. Tree or any of the Guarneri’s, but I am grateful to everything you and your fellow quartet mates have contributed to the history and the practice of this unique art form.

I hope we can meet one day.

Best wishes, Tomaz Soares.

Dear Arnold,

Thank you for telling Michael how much you loved his music , personality and all of him. It made me cry inside. I loved Michael and feel so fortunate to have known him.

Love to you

Carmit

I loved reading this tribute of my teacher and friend. Two years ago, when he passed away in March, I took the afternoon off. I planted my entire yard in hundreds of violas and pansies to honor him. It was a good feeling to bask in the sunshine of that day, to feel the coming of spring, and to work. To dwell on the memories of what he taught me, and to think of that sound you describe so well. The pattern with pansies here in Utah is that when summer arrives, they fade, and die. It’s the natural way of things. But there is a section of my yard where the little violas have continued to proliferate and reseed themselves many time over. This March is the second year they have lasted through the winter and surprised me again with their beauty and courage to defy snow and sun. There are more than ever. They have reminded me once again of the enduring love I have for my great mentor and recognize the lasting influence of a good teacher. The blooms help me reflect on all that he taught me, and can in turn, pass on to the next generation.

Leave a Comment

*/