The World of the String Quartet

June 1, 2015

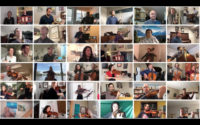

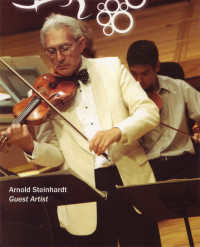

Last year, the Curtis Institute of Music, where I was once a student and where I now teach, asked me to participate in an internet course about the string quartet. Curtis, partnering with the online educational platform Coursera, has already had impressive success with two previous online courses: a survey of classical music co-hosted by Curtis faculty members Jonathan Coopersmith, chair of Musical Studies, and composer David Ludwig, and an exploration of Beethoven piano sonatas hosted by pianist Jonathan Biss. Some 50,000 learners from all over the world have signed on.

The string quartet seems such a bare-boned and unpresuming group, inhabited by a mere four musicians. You might ask what one can say that would fill an entire course about the music played by such an insubstantial ensemble. It reminds me of the old joke about a lady who goes backstage to compliment a string quartet on its performance and then adds, “I hope your little orchestra will just grow and grow.”

On the other hand, Albert Einstein once said, “Everything should be as simple as possible, but no simpler.” That is the essence, the economy, and the power of the string quartet and is perhaps the reason why some of the world’s greatest composers have been drawn to it. There is, indeed, much to say about and to hear from the string quartet.

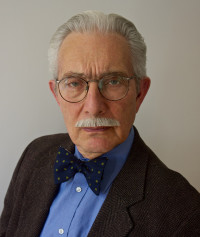

“The World of the String Quartet,” a seven-program course, went on line this April. Mia Chung, providing interpretive analysis, and I, offering a performer’s perspective, are the hosts of the show. The musical examples under discussion are performed by some of the legendary quartets of the past and present, but also by the young Aizuri String Quartet, now in residence at the Curtis Institute of Music. Along with substantive information covering almost 300 years of string quartet music, each of the seven programs ends with a segment called “With No Strings Attached,” a quiz intended to amuse and pique the curiosity of our learners.

Enough seriousness! Time to lighten up!

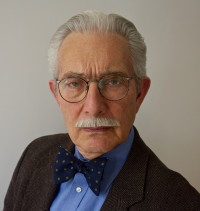

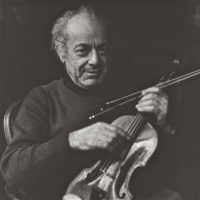

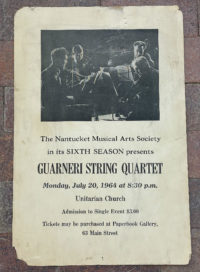

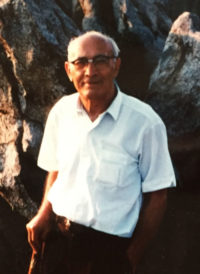

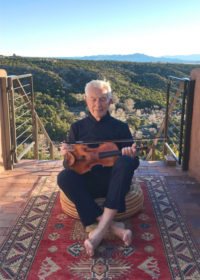

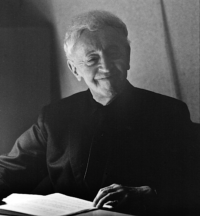

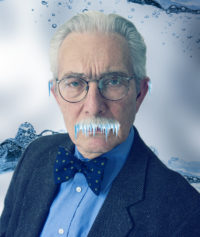

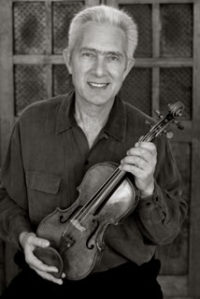

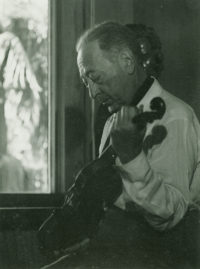

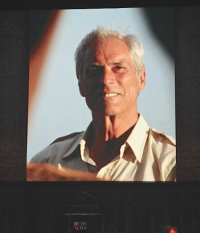

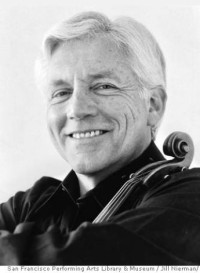

Writing material in an informative yet lively manner was challenging, and the idea of reading it off a teleprompter during filming—something I’ve never done before—gave me some pause. But the one thing I never questioned was my knowledge of the string quartet repertoire and everything associated with it. After all, I have been a member of the Guarneri String Quartet that has performed on the world’s concert stages with a repertoire of hundreds of works for 45 years. What wouldn’t I know about the string quartet?

In fact, quite a lot. Rather than be dismayed about the embarrassing holes in my knowledge, I was surprised, excited, and even tickled by some of the things I learned while doing research for the project. I felt as if I’d come upon glittering treasures both large and small.

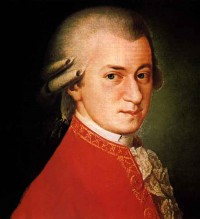

For example, I learned that the Irish tenor Michael Kelly, who spent several years in Vienna, met composers Joseph Haydn, Johann Baptist Vanhall, Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart while living there. I read that Mozart and Kelly became fast friends and often dined together, but that Kelly invariably lost at billiards to Mozart. Apparently, composing wasn’t the only thing Mozart was good at. And speaking of string quartets, Kelly reported at a quartet party in his honor, that “the players were tolerable; not one of them excelled in the instrument they played, but there was a little science among them, which I dare say will be acknowledged when I name them:

First violin….Haydn

Second violin….Baron Dittersdorf

Violincello….Vanhall

Viola….Mozart.”

Would I have loved to be a fly on the wall at that party!

Another item: The story of Beethoven’s shockingly original Great Fugue, the last movement of his String Quartet Opus 130 in B Flat Major, is well known by all professional string quartet players. People were so puzzled and I dare say upset by this audacious work at its first performance that the publisher convinced Beethoven to substitute a different final movement. What emerged from Beethoven’s pen was a charming, light-hearted movement that had absolutely nothing in common with the wild and visionary work it replaced. Well, almost nothing. Perhaps as an inside joke, Beethoven slipped what amounts to an altered version of the fugue’s opening notes into a sweetly lyrical section of his replacement movement. Sheer coincidence or slyly intentional? We’ll never know, but in all the times I’ve performed the passage, I never noticed the resemblance.

And a story for bird lovers: Antonin Dvorak, who lived and worked in New York City during the 1890s, spent the summer of 1893 visiting a Czech community in Spillville, Iowa. While composing his “American” String Quartet there, he spied a bird, the scarlet tanager, that amazed him—not only by its striking plumage, however, but also by its warble. So much so that Dvorak felt obliged to include its thirteen-note song in the Quartet’s third movement, for music lovers as well as for birds to enjoy.

photo credit: Kelly Colgan Azar

One final item: Ravel’s irresistible String Quartet in F Major and many of his other works had inspiration and support from an unlikely source. Around 1900, Ravel, along with several of his musician, writer, and artist friends, formed a kind of anti-establishment club they called Les Apaches, named after the Native American tribe but used as a word that in French came to mean “hooligan.” They met once a week, discussed art and politics, and played through each other’s newest works on two upright pianos. This was a serious group that even had its own code words and theme song: the opening melody of Borodin’s Second Symphony.

Ravel’s new quartet undoubtedly received the two-piano treatment and must have endured both criticism and praise that probably formed the last editing before its publication.

I happen to know the opening of Borodin’s Second Symphony but I doubt that would have been enough to gain me entrance into any of Les Apaches’ weekly meetings. The group of distinguished members also included none other than Igor Stravinsky.

To pique your curiosity and to provide a little amusement, here are quiz questions from “With No Strings Attached” that appear at the end of one of “In the World of the String Quartet” programs:

What string quartet music appears in at least two of Woody Allen’s movies? Which professional quartets play it? And what are the names of the films?

For anyone interested not only in the quiz answers but also in “The World of the String Quartet” seven-program course, the Curtis Institute of Music has provided the following information:

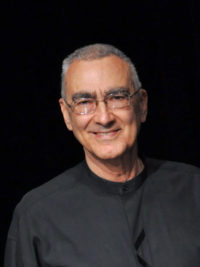

In the World of the String Quartet, a global community of learners is hearing the extraordinary stories behind great repertoire, discovering distinguished performers’ experiences, and developing keen insight as listeners. Leading their journey is renowned violinist Arnold Steinhardt and esteemed pedagogue and performer Mia Chung. Throughout the course, the brilliant young Aizuri Quartet, quartet in residence at Curtis, explores interpretation and interaction with Mr. Steinhardt.

Designed specifically for online lifelong learners, the World of the String Quartet comprises seven programs that contain brief video presentations, conversations, and demonstrations, as well as related resources, performance excerpts, and optional quizzes. One special feature is a conversation with the members of the Guarneri String Quartet about their career and their approach to being an ensemble of individuals. Each program is 90 minutes on average, and the new on-demand format makes it easy to set your own pace for listening and learning.

The course is designed to enrich listening pleasure and musical understanding for everyone, regardless of musical background. More than 4,000 people have participated in the first month. To join the class, visit the World of the String Quartet.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

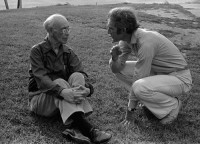

Arnold, Dave, and Michael toured Australia and New Zealand in the 1970s. I was lucky to be president of the Auckland New Zealand chamber music society. Dave cost me a lot of money by stiring an active interest in yachting. The trio taught me much about chamber music, as they liked our 1800 seat hall – which they packed out – and had to rehearse Mozart trioK563 to play on short notice. I will never forget them playing and replaying a phrase to their satisfaction -and being amazed that I could hear why. That lead to a lifetime interest and great joy for my wife and me, and we managed to pass on that interest to our daughters, which has stood them in good steadSite as they follow careers world wide. A special pleasure then to hear a somewhat older Arnold talk of his love of the genre. If you have not already done so read his book, now out of print, which is fascinating for its description of choosing new works, rehearsing old favourites and new, and for his demolition of the “first violin rules all” theory. Arnold, tHanks for encouraging a lifetime of pleasure for Jenny and me. Nigel

For several years I was fortunate – blessed – to have regular quartet evenings with Adrienne (Galimir) Krasner; Lewis Lockwood and Rodney Dennis completed our number. Adrienne, of course, was a member of the Galimir Quartet before meeting, and marrying, Louis Krasner. (As you know, Louis played the first performance of the Berg Concerto.) She recounted the experience of the Glmir Quartet’s learning the Ravel quartet for the first time. They were to perform it on the radio and were promised an opportunity with the composer, to play it for him and hopefully have his feedback. Near the start of their rehearsal a very small, painfully shy-looking old man came into the studio and sat down in a corner nearest the door. He was so very quiet Felix decided not to make an issue of his presence, even though they were expecting the great man to show up any minute. They played the whole piece. Noone else came. The little man got up and left. Later, when they asked when M. Ravel would arrive, they learned he had been at their rehearsal. The ‘interloper’ in the corner was Ravel!

Thank you so much!!! I enrolled immediately!! God bless you!! Maestro you look great!! =)

Hello Arnold. Your stories are great! Thank you from the music-loving non-musician. LZ

I’m about halfway though the course now! I’m really enjoying the insights that you bring to the two string quartets I play with–what’s great is that even amateur musicians can access that synergy and excitement of playing together. I find string quartet playing increases my confidence for tackling other challenging pieces. Can’t wait to try some of the more modern stuff you talk about!

Mr. Steinhardt, Here’s a story to add to an earlier post where you commented on music memorizing: In his 2002 book, “Piano Notes: the World of the Pianist,” Charles Rosen discusses whether audience members following along in the score is an annoyance to performers. Rosen writes that, in general and if quietly done, it never bothered him — except on 2 occasions: The score reader was sitting right in front of the stage, where Rosen could see him in his peripheral vision. Rosen says that still wouldn’t have been a problem except that this person was turning pages at different points in the score from the version from which Rosen had memorized the work. The discrepancy between his memory of the score’s layout and what his peripheral vision was showing him made him hesitate and lose his place while playing. Rosen played through to the end of the movement, stopped, walked to the edge of the stage, and requested that the score reader take a seat in the back of the hall if he wanted to keep reading along in the score. Rosen then resumed playing.

I’m in the course, and am enjoying it, even with very little musical background other than music history and uninformed listening. Thank you…and Curtis…for doing this!

I enrolled last week, and I’m loving it!!

Leave a Comment

*/