Opus 130

October 3, 2011

Not long before I graduated from the Curtis Institute of Music in 1959, John Dalley, a fellow violin student, asked me whether I’d like to work on Beethoven’s late String Quartet in B Flat, Opus 130. The Paganini String Quartet had recently performed at the school, ending their program with another late Beethoven Quartet, Opus 132 in A Minor. I had never heard the A Minor Quartet before, but sitting with the other students in Curtis Hall awaiting the performance, I expected music of the highest order. This was our great Beethoven after all. But Opus 132 transported me far beyond its stunning craft and originality. Especially during the slow movement in which Beethoven gives thanks to God for having recovered from an illness, I had the odd sensation of having left my life of ordinary experience behind. I felt like a space traveler visiting areas of unimaginable breadth and substance.

I accepted John’s offer eagerly. Without quite knowing what I was getting into, I must have hoped for another late Beethoven experience. John asked whether we could choose the original last movement, the Grosse Fuge (Great Fugue) rather than the one Beethoven later wrote as a replacement. He explained that the Grosse Fuge was so shocking and unintelligible on first hearing that Beethoven’s publisher asked him to write a substitute movement. My pulse quickened. The Grosse Fuge might just be my next other-worldly adventure. John Dalley, first violin, I second, Jerry Rosen, viola, and Michael Grebanier, cello, four highly enthusiastic but inexperienced students, began rehearsing soon after. Opus 130 has six movements rather than the usual four. One by one we read as best we could through each of them.

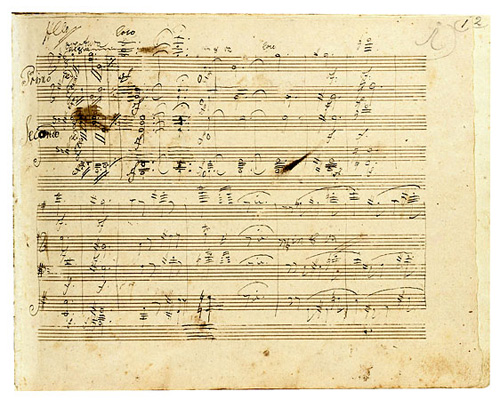

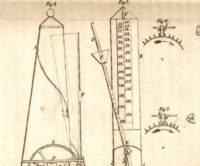

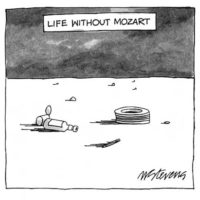

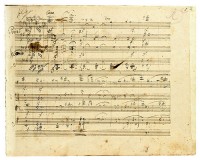

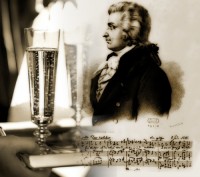

Manuscript of Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge, arranged for piano four hands, 1832, Juilliard School of Music Manuscript Archive

Four slow, quiet, but suspenseful notes in octaves and unison opened the first movement’s introduction, Adagio ma non troppo. The voices blossomed gently into rich harmony and flowed forward in stately, almost processional fashion. Then the main Allegro burst forth with notes rushing headlong under a five-note figure that seemed like a military call to action. (Was Beethoven summoning us?) A second theme began as soaring melody and then veered into scurrying clusters of sound; and throughout the movement, shards of the opening introduction appeared again and again as evocative flashbacks. Imagination. Substance. Daring. This was the Beethoven of my dreams. I expected nothing less from the other movements as I turned the page.

To my surprise, I discovered that Beethoven had decided instead on fun and games for the second movement. The Presto‘s mood was sparkling, giddy, even recklessly jaunty, but then came yet another surprise. The party mood was jarringly interrupted mid-way by unabashed buffoonery in the form of odd scales, eccentrically drawn-out notes, and peculiar outbursts—a circus clown played the fool for laughs here. The movement’s high spirits were irresistible at that first hearing, but also inexplicable. How could these first two starkly different, seemingly disconnected movements exist side by side?

The third movement presented us with an altogether different mood. Clippity-clop went the good-natured and affable opening rhythm. Fragments of good-natured melody surfaced here and there, interspersed with beads of playful running notes. We had left the circus (on horseback?) and were now traveling leisurely through bucolic countryside.

With the fourth movement, I braced myself for yet another surprise, but not much of one was forthcoming. The Allegro assai, subtitled Alla danza tedesca (In the manner of a German dance), was nothing more or less than a simple rustic melody repeated in various disguises. You might say that our horses had happened on a peaceful summer outing filled with singing and dancing by the local inhabitants. The movement exuded warmth and goodwill, but that unsettled me on first reading. Where was the visionary Beethoven, the man whose late quartets by reputation traveled into unexplored depths of feeling and experience?

The Cavatina, Adagio molto espressivo, the movement that followed, began with a simple rising and falling of the second violin’s first notes, and then eased into hymn-like four-voiced music of heart-felt beauty. The word Cavatina originally described a short song of simple character, but Beethoven re-imagined the form. The extended opening section, moving as it was, then led into one of the most deeply affecting moments in music. While the lower three voices laid down a ghostly pattern of repeated triplets, the first violin wove imploring but tentative notes far above, almost none of which coincided with the ongoing rhythm. The first violin served as a proxy for someone who seemingly had lapsed into disorientation and hopelessness. The effect was one of gathering desperation. Beethoven marked the word “Beklemmt” above this passage, loosely translated as “oppressed” or “anguished”. The music, almost unbearable in its utterly gripping message, finally released its hold and returned us to a slightly altered version of the original material. Then the movement ended with several pulsating chords dying away in melancholy resignation. Beethoven, although deaf at the time, was said to have wept upon hearing the Cavatina in his inner ear. This then, was my long wished for space travel—a voyage not outward bound but rather one into the recesses of the heart, mind, and soul.

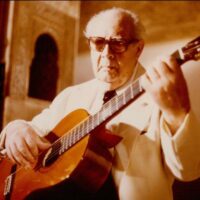

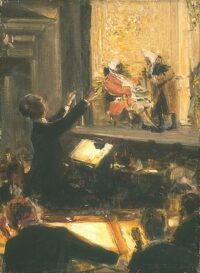

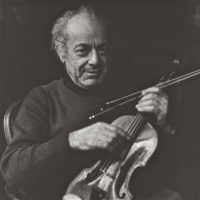

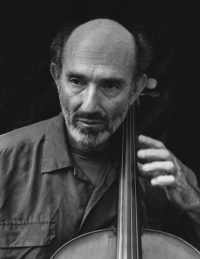

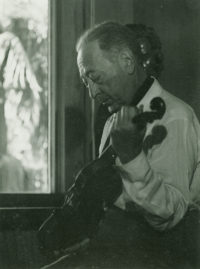

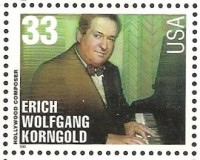

Guarneri Quartet playing the Cavatina, Adagio molto espressivo

And then from this exalted state, Beethoven opened the trap door and dropped us four wide-eyed students into a world of near chaos for fifteen minutes. The Grosse Fuge, the sixth and final movement of Opus 130, began with a twenty-four bar Overtura that limped breathlessly with strange fits and starts to the fugue’s beginning. The fugue itself, actually a double fugue with two subjects, was violent and dissonant. Dramatically leaping tones and slashing cross-rhythms threatened to burst into anarchy. A series of extended sections in contrasting keys, rhythms, and tempos followed the fugue. Then small fragments of the fugue subjects made their quirky entrances before the movement finally gathered momentum and rushed with manic elation to its end. At first, critics called the Grosse Fuge “incomprehensible as Chinese” and an “indecipherable, uncorrected horror”. Much later, Igor Stravinsky saw it more clearly “as an absolutely contemporary piece of music that will be contemporary forever”. In years to come, I would begin to understand the Grosse Fuge in sober structural terms, but as its last notes rang out for the very first time, a feeling came over me that no other work has elicited before or since. The Grosse Fuge was more than music. It was an overwhelming act of nature.

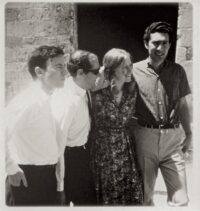

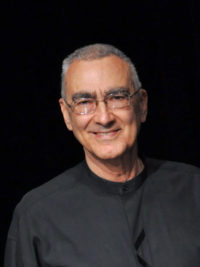

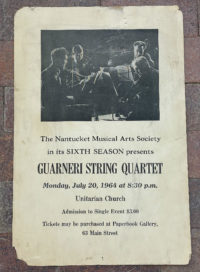

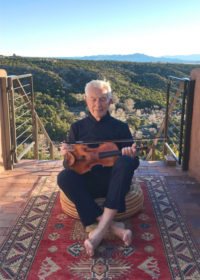

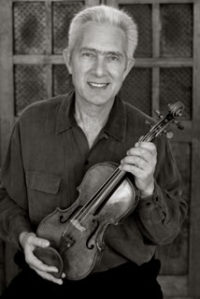

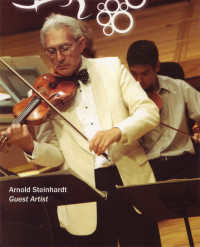

John, Jerry, Michael, and I worked on Opus 130 for the better part of the school year. We discussed, we argued, we reveled in the miracle this music was, and we groaned over the technical and musical challenges it posed. Finally, we performed Opus 130 in Curtis Hall. In the Menno mosso e moderato section of the Grosse Fuge, a moment of peace in the eye of the storm that surrounds it, I was suddenly overcome with emotion. We had worked hard and the performance was going reasonably well. I looked up in gratitude at my friends who had shared in this great adventure. Mistake. When I looked down again at the sea of notes before me, I had lost my place. For a few seconds that seemed like an eternity, I struggled to find my way back into the music. My lapse of concentration was embarrassing at the time but I look back at it now with different eyes. In 1964, only some six years later, John Dalley, Michael Tree, David Soyer, and I formed the Guarneri String Quartet that would perform Opus 130 and a host of other quartet masterpieces for the next 45 years. Without consciously realizing it, that first late-Beethoven encounter had changed my orientation and headed me toward the all-engrossing world of string quartets. I had not lost my place. I had found it.

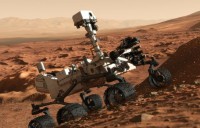

The concept of other worldliness or outer space seems apt in describing the uncommon elements of Opus 130 but in fact, the Cavatina is literally traveling away from earth to distant parts of the universe as I write. The Budapest String Quartet’s rendition of the Cavatina was chosen by NASA as the last piece on the “golden record”, a phonograph record containing a broad sample of Earth’s common sounds, languages, and music. The record was sent into outer space with the two Voyager probes in the hope that intelligent extraterrestrial life would eventually discover it. I can’t help wondering what the aliens will think about that “Beklemmt” moment.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

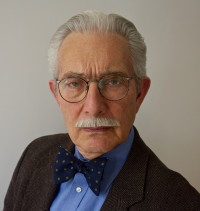

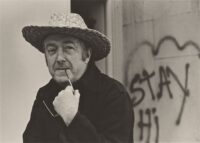

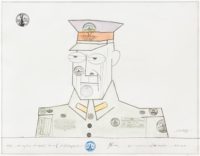

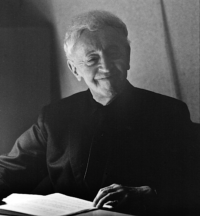

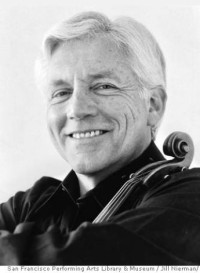

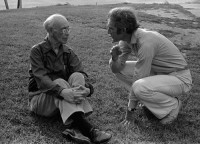

Arnold, the portrait you allowed me take of you [page 66 of String Quartet Playing] just before your 28 February 1978 Berkeley concert featuring Beethoven Opus 131 perfectly depicts your passion

Beautiful. Just beautiful.

Beyond my thoughts, I am Glad You Did The “Work”.

I gave my husband “Violin Dreams” over the holidays and am now taking a spin through your blog. I’m so taken with this entry; in many ways it describes how I felt the first time I read Virginia Woolf’s “To the Lighthouse.” A force of nature indeed.

I could not understand the late qutretas until I was past the ager of 60 .many have the same experience.What helped me tremendously is J N Sullivan’s book Beethoven and his spirituality; he dissects the middle and late qutretas and I hear what he hears he ascribes quite specific meaning to the individual movements of these masterpieces, and they all fit. Mainly I think the late qutretas reflect Beethoven’s loneliness, his despair at being an outsider (so easy to forget he was totally deaf) and his vision of the possibility of happiness in another state of being/life. There is such utter despair in some of the movements, it can be quite painful to listen to.I highly recommend you all read Sullivan’s book; there are many insights, not just into the music of the qutretas.I love your commitment to music; you are so utterly sincere and very exciting; your attention to dynamics and phrasing are exceptional. Your Mendelsson disc is a particular favourite isn’t that early quartet just amazing in the way he absorbs the essence of the late qutretas?!

Dear Mr. Steinhardt,

I’ve been working on an animated graphical score of Beethoven’s Große Fuge. Here is a recent draft: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JG47mxCMfrI

I hope you enjoy this.

Sincerely,

Stephen Malinowski

Music Animation Machine

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephen_Malinowski

Leave a Comment

*/