Lulu

February 4, 2016

No one ever dies in chamber music. The thought occurred to me while I was on the way to the opera. People die right and left in opera. Madame Butterfly, Tosca, Carmen, Romeo and Juliet—they all die. I’ve played in a professional string quartet most of my life, but nobody dies there. Yes, there are lows as well as highs in the repertoire, desolation as opposed to exuberant optimism, but at no time have we in the Guarneri Quartet unsheathed fake stilettos and enacted murder during a late Beethoven string quartet.

Someone coming directly from the opera world to a string quartet concert might feel sorry for the listener. Four musicians play away on the stage, but why aren’t they singing and where are their costumes, the full orchestra, the stage sets, the stories, the drama, and—now and then—the murders?

I think of the string quartet form as music boiled down to its most essential and meaningful. As Albert Einstein once said, “Things should be as simple as possible, but no simpler.” In that sense, there is nothing more moving than a Mozart, Schubert, Mendelssohn, or Bartok string quartet.

Especially coming from my musical background where less can sometimes be more, I am thrilled to go to the opera now and then where more can often be, well, more. And so, there I sat expectantly the other day at New York City’s Metropolitan Opera as the conductor gave the downbeat for Alban Berg’s Lulu. I was not going to be disappointed. With the clamor of brass braying in a seconds-long splash of atonal sound, the curtain parted and out stepped the opera’s circus animal trainer. “Come on in to the menagerie,” he boldly announced, and then went on to describe its animals: tigers, bears, monkeys, and, finally, as the curtain opened, the snake. Of course, the menagerie was a thinly disguised description of humanity with all its warts, and the snake was Lulu—the source of evil, fated to murder without leaving any clues.

For the record, there would be five murders and a suicide in the course of the four-hour opera.

The impression made on nineteen-year-old Alban Berg by Karl Kraus’s production of the German playwright Frank Wedekind’s two Lulu plays, Pandora’s Box and Earth Spirit, was overwhelming and long lasting. Lulu, half innocent, half predator, lures both men and women sexually and emotionally to their eventual deaths and, finally, to her very own. After the international success in 1926 of Berg’s first opera, Wozzeck, he set to work fashioning Wedekind’s Lulu plays into his next opera, Lulu. Like Wozzeck, Berg desired to explore the dark and twisted corners lurking in the human heart.

There would be one more death associated with Lulu and that was of the composer himself as the opera neared completion. An insect sting that had become infected was the senseless cause of Berg’s tragic death but the opera might nonetheless have been finished if not for the young American violinist Louis Krasner. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, they deemed Berg, his teacher Arnold Schoenberg, and many other forward-thinking artists as degenerate—in effect closing the door to Berg’s future concerts and thus to a source of income. Krasner, whom I knew late in his life as a musician’s musician, offered Berg fifteen hundred dollars to write a violin concerto for him. Temporarily setting Lulu aside, Berg accepted Krasner’s commission, giving us a glorious violin concerto in the process but leaving Lulu’s third and final act not quite complete. The opera was only finished by other hands decades later, based on the composer’s sketches.

As the performance of Lulu that I was watching got underway, Berg’s atonal language seemed dense and forbidding at first (a single twelve-note series allotted to Lulu apparently determines the entire opera’s musical action). But gradually the music revealed its true post-Wagnerian angst and an almost reckless romanticism, aided by the unusual addition of piano, saxophone, and vibraphone to the full orchestra. The sheer abandon of the performance by both orchestra and singers reminded me of a personal encounter with Berg’s music, one only a step removed from the great master himself. Several years ago, my friend and mentor, the violinist Felix Galimir, attended a Guarneri Quartet performance of Berg’s String Quartet, Opus 3. I called Felix the next day for his opinion of our rendition. For easily half an hour, he explained over the phone in great detail what he had liked, where we had failed to sufficiently honor Berg’s detailed instructions, and where we could have been more rhapsodic above and beyond the printed notes.

Indeed, this is what Berg himself had done with the young Galimir Quartet (comprised of Felix and his sisters, Adrienne, Renee, and Marguerite) during their rehearsals of his music in Vienna. Felix told me that although Berg, who sat in on all rehearsals, was a stickler for following his detailed musical instructions, ultimately it was the music’s sheer sweep and romanticism that mattered most to him.

The lurid tale of Lulu is not for the faint of heart, and yet there was something mesmerizing about this performance’s journey into darkness, especially in light of the South African visual artist William Kentrich’s eerily spellbinding production. But the essence of the opera rests obviously with Lulu herself, here performed by the German coloratura soprano Marlis Petersen. Petersen, who has performed Lulu in ten productions over the past eighteen years has earned the right to call this her signature role. Vocally, Petersen was able to careen back and forth from sweetness and refinement to sheer raw power, while managing Berg’s jagged leaps of pitch that occasionally pierced the stratosphere with apparent ease. But more to the point, she seemed to actually become Lulu. Now forty-eight, she managed to exude the half-aware but unfolding sexuality of the fifteen-year-old Lulu, allowing men to build an image of the young girl based on nothing but their own fantasies.

Thanks to Peter Lloyd, my friend and colleague, I had been able to meet his long-time friend Marlis several years ago after a performance of Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro in which she sang the role of Susanna. When we joined Marlis at a party after that performance, I found her to be charming, witty, independent-minded, and with pixieish qualities that seemed to lend themselves perfectly to the role of Susanna she had just performed so brilliantly.

But Lulu? Peter and I had gone backstage to see Marlis after her emotionally shattering performance. There she stood in her dressing room smiling broadly, and jumping up and down as if she were on a pogo stick when she saw the two of us approaching. Marlis had at least outwardly left Lulu on stage as she warmly greeted a throng of admirers, but I wondered about her connection to the role—clearly a deep-running one. Was Marlis, herself a beautiful and alluring woman, drawing inspiration from skeletons in her own closet—perhaps a string of lovers who had died or been murdered at her hands? Probably not. More likely, Marlis had fashioned the role of Lulu not only with her exceptional artistry, but also with an awareness of the darker side of the human condition that lurks in all of us. That is what Frank Wedekind wrote about, what Alban Berg composed, and perhaps why we continue to be drawn to Lulu, the opera and Lulu, the woman, at the safe distance of art rather than the grim reality of life.

I went to see Lulu a second time several days later. Coming from my intimate world of chamber music, the opera had almost overwhelmed my senses the first time around, but perhaps even the most dyed-in-the-wool operagoer would have felt the same. Alban Berg’s music, often dense, florid, and intense, requires full attention, as do the twists and turns of Lulu’s lurid story. Add to that the breathtaking singing and acting from the entire cast and William Kentridge’s wildly imaginative and affecting production, and you are wondrously in danger of sensory overload.

I was happy to have a second chance at taking in the opera’s complexities, but that’s not why I was there. This evening was to be Marlis Petersen’s last performance ever in the role of Lulu. Filing into the Met with the rest of the crowd beforehand, I heard the man behind me tell his wife, “You know she’s going to scream herself tonight.” There had been lots of media attention not only about this final performance by Marlis but also that she herself would let out the scripted bloodcurdling scream as Jack the Ripper murders her. To save her voice for future performances, a stand-in had always screamed for Marlis, but there would be no more future performances.

Marlis’s last scream was indeed bloodcurdling but the entire four-hour performance seemed to have a special edge to it. But perhaps this was only my overworked imagination, knowing that the intimate eighteen-year relationship between Marlis and Lulu with all its unimaginable implications was finally coming to an end.

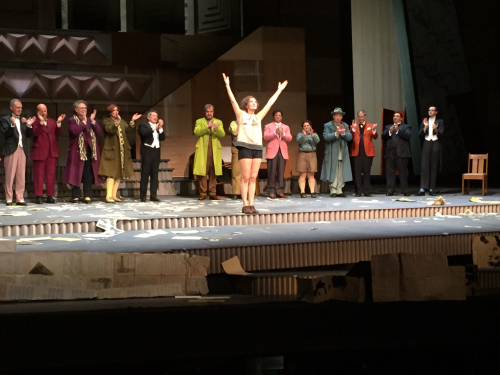

Final curtain

At the post-performance party, I met several of the cast, some of whom according to Berg’s instructions had played multiple roles. I met bass-baritone Martin Winkler who was the theatrical animal trainer, bass-baritone Johan Reuter, the grisly Jack the Ripper, mezzo-soprano Susan Graham, the lesbian Countess Geschwitz, baritone Franz Grundheber as Schigolch, possibly Lulu’s father or lover or both, and I met the young woman who sat at the piano stage right in the first act and who by the third act was IN the piano, now stage left, with her legs seductively protruding and moving bizarrely as accompaniment to the ghastly action being played out on stage. All of them, frighteningly convincing in their various roles, seemed so affable, so normal now in conversation. You might say that we string players also assume roles in the music we play, in the emotions or moods we try to convey, but sheer sound alone is quite removed from the reality of daily life. There we sat, Jack the Ripper and I, with glasses of champagne in hand, talking casually about his next gig only moments after the guy had, for God’s sake, just murdered poor Lulu.

The party’s jubilant spirit finally reached the point where a spontaneous call went up for the triumphant but now exiting star of Lulu to speak. Marlis, claiming she had prepared nothing to say, nonetheless managed to find moving words to describe her long relationship with Lulu. She confessed how melancholy she had become as her second to last Lulu role came to an end in Munich, and that with the last scream on the Met stage, she and Lulu had finally made peace with one another. With a smile, Marlis told us she wished Lulu well as she took up residence perhaps on some distant planet.

Peter LLoyd, Marlis Petersen, and Arnold Steinhardt back stage

On the way home from the party, Marlis’s last words brought me back to the world of chamber music and Arnold Schoenberg’s Second String Quartet with Soprano—the moment in which Schoenberg introduced the world, and his then student Alban Berg, to atonal music. Berg must have also known that the work’s radical harmonic language was in part an expression of Schoenberg’s painful personal story involving both adultery and suicide at the time of writing. (There is death in chamber music after all).

In the quartet’s last movement, Schoenberg provides the vocal part with an evocative poem “Entrückung” or “Transport” by Stephan George. The poem’s first line is “I feel air from another planet.”

For impressionable student Alban Berg, might such a planet have been Lulu’s birthplace and, in Marlis Petersen’s imagination, her final refuge?

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

Of course, Leoš Janá?ek might disagree with the statement that nobody dies in chamber music!

Delightful blogpost, Arnold. Thank you!

Your piece fondly evokes the ‘Second Vienna’ as only the special authenticity of a performer’s musings can. Thank you for this piece!

Thank you for writing this piece as well as your blog!

I had the privilege of studying the Berg violin concerto with L Krasner before leaving the BSO in 1987. He was very generous with his time as well as many of hi stories. He mentioned how Berg interrupted composing Lulu in order to write the concerto.

On the last day when leaving Krasner’s home in Brookline, I asked him how I could reciprocate for all the precious time he so generously gave me? His answer was very simple “go and play, perform the concerto. Do if for Berg as he has done so much for me”

I performed the concerto six times and each time it was a new spiritual experience I will never forget!

Leave a Comment

*/