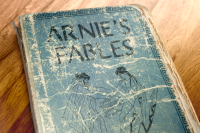

The Swan

December 1, 2008

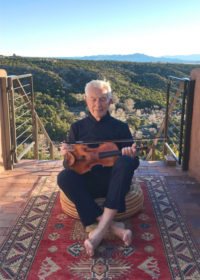

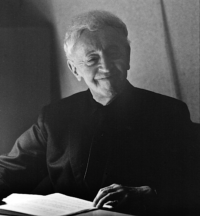

When I was eleven years old, my violin teacher assigned me The Swan by Camille Saint-Saëns. I had no idea that The Swan was a famous cello solo or that it was part of a much larger work, The Carnival of the Animals. I had never even heard of its composer, Saint-Saëns, or seen his name in print before. I wondered why there was a funny line between his two-word last name and what could be the purpose of those strange dots perched on top. And was Saint-Saëns actually a saint?

I thought that The Swan was very pretty and probably associated the music’s title with its general mood in some vague way. As a child, I often saw swans gliding regally through the water on the lake near where I lived. Accompanied by the piano’s gently rippling arpeggios, Saint-Saëns alluring melody seemed to convey the swan’s very essence.

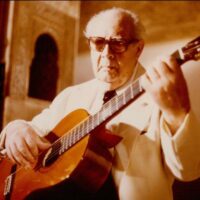

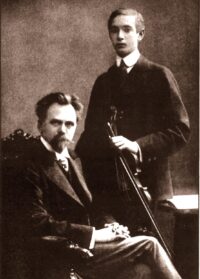

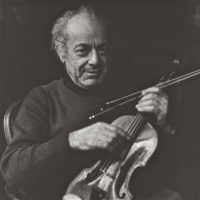

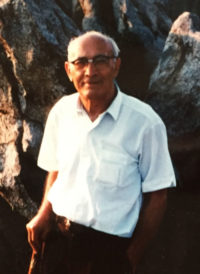

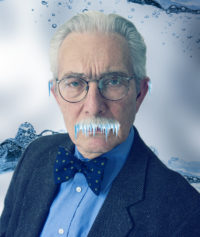

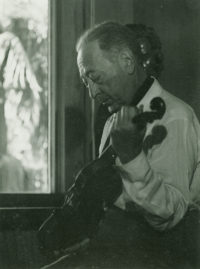

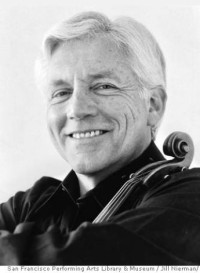

I must have heard dozens of student cellists play The Swan in my teenage years but I gave it little thought. I was a violinist after all, not a cellist. Later on, however, a chance set of circumstances brought me face to face with the work. While I was assistant concertmaster of the Cleveland Orchestra, I shared a house for a period of time with Jules Eskin, its principal cellist. Over coffee one morning, Jules told me that The Carnival of the Animals had been scheduled for a future concert and that he would be playing the cello solo. From that point on, Jules practiced The Swan daily. The snippets of phrases I occasionally heard as I passed in and out of our house sounded beautiful, but Jules, apparently unsatisfied, continued to work on The Swan. I was amused at first. Granted, it was a lovely melody but how much time can one devote to something so simple, so naïve.

One day, Jules called me into the living room where he practiced and asked my advice on how to shape a particular phrase. He played the phrase and looked up questioningly. To the best of my recollection, it sounded utterly convincing in Jules’ hands and for the moment, I could think of nothing to say. He played the same phrase once more with a small but discernable difference. I remember voicing an opinion and then offering a suggestion or two. Jules played the phrase again and again—softly and intimately in one version, more intensely in another—pausing each time so that we could talk about the phrasing inflections he had just crafted. Finally Jules thanked me for my input while ruefully concluding that he was still not sure what was best. Our discussion about a section of music lasting no more than fifteen seconds had taken easily five minutes.

The Swan’s shapely contours and enticing harmonies refused to leave me as I left the house. The melody, a full three minutes in length, gave the illusion of being disarmingly simple and yet, was it really so simple? Jules and I, behaving like scientists looking at a specimen under a microscope, couldn’t even agree on a single phrase.

The next morning at breakfast, Jules and I pushed other subjects to the side and began discussing The Swan in more detail. Since our last conversation we had independently come up with new ideas. Jules quickly became impatient. “Let me just play the whole thing for you. Then we can talk.” He took out the cello and bow and played Saint-Saëns’ melody from beginning to end. Jules’ playing was ravishingly beautiful but he shook his head as the last note faded away and suggested several possible phrasing alterations both small and large. Unfortunately, everything in music is connected. Change one note or one phrase even slightly and everything around it has to be re-evaluated. Our discussions became lengthier and more detailed. The Swan’s possibilities seemed endless. In the coming days, Jules continued to practice and I stepped into the living room more and more. An eavesdropper might have thought we were probing the depths of a late-Beethoven string quartet.

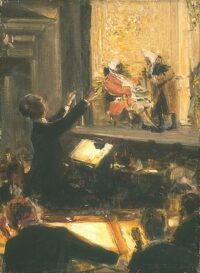

Jules performed The Swan beautifully, but I also came away from the concert with a new found respect for what Saint-Saëns had fashioned. A great melody—anything from Taps to Beethoven’s Ode to Joy—has a palpable structural integrity, a sense of proportion, an unerring rightness to it. As Jules spun out The Swan‘s extended aria accompanied by the gently rocking arpeggios scored for two pianos, I had the sense that every note and every phrase was in its rightful and inevitable place. Saint-Saëns must have thought so, too. This is the only movement from the Carnival of the Animals that he found worthy enough to be played in public during his lifetime.

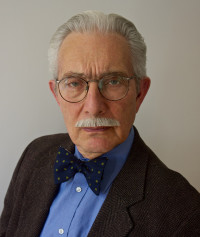

Long after the event, David Cerone, the then president of the Cleveland Institute of Music, asked me to give a violin master-class at the school. He requested that I choose the repertoire. I hadn’t thought of The Swan in years, but somehow it popped into my head. Remembering the labor Jules had put into the piece and thinking that these young fiddlers might be challenged, I suggested it to David. He smiled, clearly taken aback, thought about it for a minute, and then agreed.

At the appointed hour, approximately fifteen violinists and one piano accompanist filed into the conservatory auditorium. I can only imagine what the students thought of their assignment. Master-classes usually deal with serious repertoire—a Beethoven violin and piano sonata or a Bach work for solo violin, for example—but The Swan? The Cleveland Institute of Music, one of the country’s premier music schools, has always had first-rate violin students and this group was no exception. Fifteen times, the accompanist played those gently rocking opening notes, and one by one, fifteen violinists played The Swan. Some performed with mechanical precision, some displayed a solid musicality, yet none managed to play in a way that I could honestly call affecting. For the moment, The Swan had defeated them all. One of our tasks as musicians is to examine the elusive structure of a melody, the most basic building block of music, and to take it apart note for note, phrase by phrase, in order to understand it as best we can. Then we must put it back together cohesively and affectingly. The students and I worked for the next two hours to uncover the music’s essence, to turn groups of notes into the regal bearing of a swan—precisely what Jules had done as he practiced those many years ago.

I would not be entirely accurate or fair without mentioning one specific student who participated in the class that day. Mary Hess, a double major in both violin and voice, had played The Swan reasonably well, but it occurred to me that she might sing it quite differently. Mary obliged by placing her violin and bow in its case and repositioning herself on stage without instrument. The pianist played the opening harmonies once again and Mary sang the entire melody for us with simple yet affecting beauty. Teachers are forever coaxing students to rise above their chosen instrument and sing. Mary did so literally and for those unforgettable moments, she became the swan itself.

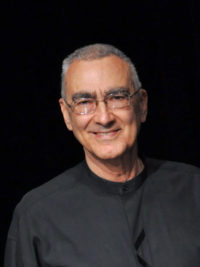

Jules Eskin has now been the principal cellist of the Boston Symphony for many years and I live in New York City, yet we still manage to see one another occasionally. I brought up our Swan encounter recently. To my surprise, Jules had no recollection of the fierce battle he once waged with a swan in his living room some fifty years ago. The event must have made some subliminal impression on him, however. Jules told me he asks cellists auditioning for the Boston Symphony to play The Swan. He looks for musicality, tone production, intonation, bow control, and artistry in a prospective cellist. Jules said, “Once I hear a cellist play The Swan, I know absolutely everything I need to know.”

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

Arnold,

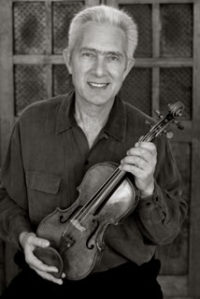

The Swan is indeed a fascinating and difficult piece. My fav tale is the day Isaac Stern was invited to play the piece as a prima ballerina danced it in NYC. Sorry I don’t remember the company whether Bolshoi or ABT.

Isaac had a bunch of intonation stuff during the TV performance and commented afterward that he was so emotionally involved that he couldn’t play! I totally understand since we classical players tend to go inside ourselves to find a safe haven for emotion and technique to intersect. Playing with a dancer doing her thing is definitely not a safe haven.

Another time long ago when I was a kid in SF, it was the Bolshoi with their great dancer all in black doing the Swan. She was so unbelievable that us audience wouldn’t stop clapping. The cellist in the pit had to play it 3 times! How the dancer managed to maintain her poise and command through 3 back to backs I’ll never know. But an unforgettable experience for a 10 yr old!

Bermard Chevalier

Leave a Comment

*/