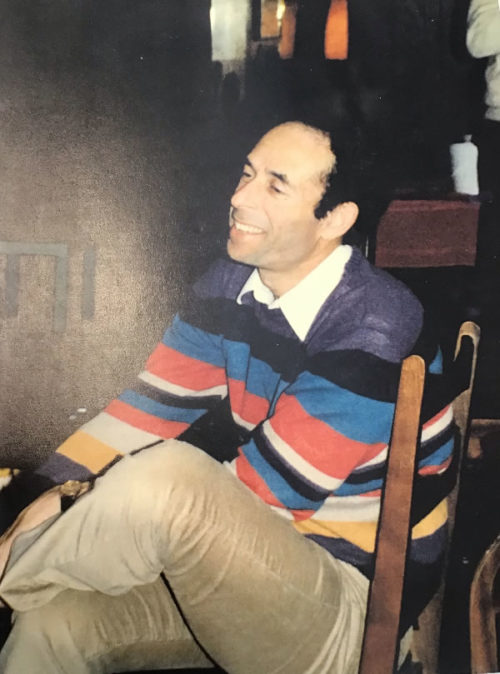

Mike Robyn

August 11, 2021

Something deeply personal inevitably takes place between a performer and his audience. You might call it an act of generosity rather than a concert performance, or, put differently, the need to share thoughts and feelings about a work of music with others rather than simply keeping it to oneself. The pianist Arthur Rubinstein told a class of music students that he was once practicing in his apartment when the janitor unexpectedly came to fix the plumbing. Without really thinking about it, Rubinstein found himself performing for the man—his overwhelming desire to share the music paramount. And I suspect, without any kind of proof, that performing a work for an audience comes out differently from playing it for oneself.

But as intimate an act as performance is, it has its boundaries. Listeners have no idea of my personal life when I’m playing, say, a Bach solo sonata for them, and I have no idea of theirs. What if they knew that I had just recovered from a serious illness or that my best friend is getting married tomorrow? What if I knew that some in the audience were inner- city kids from a local high school, or that an elderly couple in the front row were holocaust survivors? Would that knowledge make any difference in the way music was rendered or received? In any case, this is for the most part an abstract discussion. I have rarely known anything about my listener’s lives, nor they about mine.

That is, until Debby called me.

Debby and I have been friends since high school. The glue to our beginning friendship was the love of music. Debby played the harp, I, the violin. And while my parents were passionate music lovers, Debby’s were actually professionals—her mother, Frances Robyn, a pianist, her father, Paul Robyn, a violist, who for many years was a member of two distinguished string quartets, first the Gordon, and later the Hollywood String Quartet.

Although our friendship has lasted to the present day, the fact that Debby and I have lived in different parts of the country made for sporadic person-to-person visits. And so, since we occasionally spoke on the telephone in between, receiving the call from her around 1999 seemed perfectly normal.

But rather than normal, Debby’s call was shocking. “I would never dare to ask this kind of favor of you, ordinarily,” she began, “but my younger brother, Mike, has Lou Gehrig’s disease. Would you play for him?”

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, more commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease after the baseball player who suffered from it, is a progressive nervous system disease that affects nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. Eventually ALS affects control of the muscles’ ability to move, speak, eat, and breathe. There is no cure for this fatal disease.

The news that anyone I knew had come down with ALS was devastating enough, but my enduring memory of Mike was that of a healthy, thriving teenager practicing basketball shots through the hoop attached to the Robyn’s garage.

Although Mike loved music deeply, he went on to become a brilliant electrical engineer. His knowledge both abstract and practical was far ranging enough for him to be sought after as a problem solver/trouble shooter by the Aerospace Corporation that monitors the Air Force’s space and communication projects.

I accepted Debby’s invitation to play for Mike with the feeling I’ve often had, but now was stronger than ever, that we performers are in some kind of service profession. My hope was to give Mike comfort and meaning as well as enjoyment while he battled this pernicious disease. I arranged with Mike’s longtime friend, the pianist Robert Silverman, who often visited him from British Columbia, to be in Los Angeles at the same time. There would be two of us offering solace to Mike through our music making.

When the concert took place, Mike in his wheelchair was rolled into their living room where the piano stood. In attendance were his wife Abby, their two daughters, Sara and Anna, and his mother, Frances. By this time Mike was on total life support. He had lost the use of almost everything in his body except his abilities to think, to hear, to see, and to blink. He used that last ability to laboriously convey messages to his loved ones.

I cannot exactly remember what Robert and I played for Mike that afternoon, but as we prepared to perform I could not help trying to imagine what was going on in Mike’s still brilliant but entrapped brain, and the emotions that listening to live music would elicit in him. Would he think, “Ah, such sweet sounds. I’m so touched that you’ve come to play for me,” or would there be for Mike a heightened awareness, a riveting potency and meaning to the music that none of us could even begin to imagine?

I must have said something to Mike afterwards and later received a blinked thank you from him. Abby told me that, for an afternoon, Robert and I had offered Mike an escape into another wonderful world, and what a gift that was. Through the mystery and magic of music, we were able to reach out to a man who could no longer move or speak, but could still listen, think, and feel.

In 2010, Mike passed away at the age of seventy. Despite the cruel advance of his disease, he managed to stay alive long enough to attend both daughters’ weddings and to enjoy two little granddaughters.

Rest in peace, Mike.

Mike Robyn, early 1990’s.

Subscribe

Sign up to receive new stories straight to your inbox!

Comments

So moving, Arnold – thank you – music transcends both life and death – I cannot imagine a more appreciate audience than Mike Robyn – RIP

Thank you very much for sharing this touching story. Between an audience and a performer, a play, a film, isn’t a most intimate conversation of souls ? Take good care of you, mister Steinhardt.

Thank you for this touching story. It brought tears to my eyes.

Such a touching story Arnold and how wonderful to have the ability to

offer such a gift to someone who needs it so badly!

Arnold. This is beautiful , and yes, frequently as I sit raptured in the Marlboro music concert hall into mind wanders to Mitsuko, or Jonathan or Leon or Peter or you! And I wonder, for a moment,about your thoughts, feelings, and believe how immersed you are in that moment. I’ve missed seeing you on Potash Hill this precious season. I trust you and family are well. I send love and frtfir all the magnificent gifts you give us. Be well. Be safe.

What a wonderful thing to do. The story made me teary but in a good way. You are not only a gifted musician but you are also a great friend.

Hi Arnold! This is a heartfelt story and your kindness in performing for your ill friend is immense. Diana recently told me that your brother died and I send you my sincere condolences. Fortunately, Marlboro Music completed its season without illness, but lingering COVID increases the need for your music-making as a respite from the again rising pandemic. Stay well. You are missed.

or better not to think about it ))

http://breakerin.gq/chk/3

Leave a Comment

*/